I often assert that Colorado is one of the best soaring locations in the world. Powerful mountain thermals, long convergence lines, and 20k ft cloud bases are common and quasi par for the course.

Why then is it that no one has ever completed a declared 1000 km FAI triangle?*

*An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that there had never been any declared 1000 km flight in Colorado (with up to 3 turnpoints). While none were officially recorded as a state record, this is not true. Dave Leonard completed a declared 1000 km flight from Kelly Airpark in 2001 in an LS6. In 2005, he was followed by Tom Serkowski who flew a declared 1000 km out and return in his ASH26E also from Kelly. There have also been numerous free six-leg OLC flights over 1000km, from Boulder, Kelly, and Owl Canyon. But as far as I know there has not been a declared 1000km FAI Triangle.

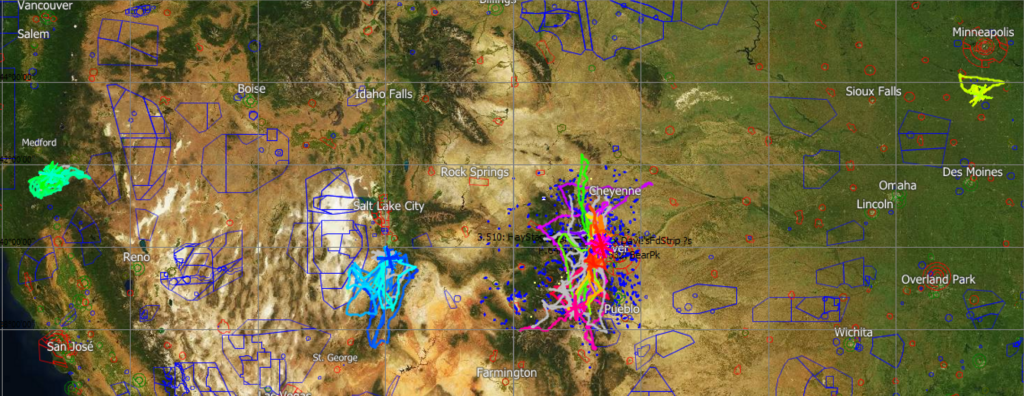

This spreadsheet lists all 1000km flights per OLC rules (max of six legs) ever recorded in Colorado (37 flights by 11 pilots as of this writing, as far as I’m aware). The list is in chronological order from the first to the most recent. I also included a most remarkable downwind dash by Alvin Parker in 1964 who flew from Odessa, Texas in a straight line to Kimball, Nebraska in a Sisu 1A sailplane. Although the flight neither originated nor ended Colorado, it crossed Colorado from south to north and is more than worthy of being listed here. It was a new world distance record at the time as is reported in detail in the September 1964 edition of Soaring Magazine.

As of this writing, only three of the 1000 km flights in Colorado were declared 1000+ km flights that were also completed. 1000km declared FAI triangles had been attempted a few times, most notably by Tom Serkowski, but for a variety of reasons none had been successfully completed. Please email me if you see anything here that’s incorrect or if there is a flight that I may have have omitted.

An Exceptional Flight Requires Exceptional Conditions

As I explained in my recent article about the Colorado 14er Challenge, a key reason for why we have not seen any completed 1000km FAI triangles in Colorado before, is the complex soaring terrain: the many tall mountain ranges tend to divide the state into different air masses and weather systems. It is exceptionally rare to find a day that works all across Colorado. But that is what you need to plan and execute such a flight.

Another factor is the length of the available thermal day. If the air is unstable enough for the day to develop early, there’s often overdevelopment and thunderstorms by early afternoon. If the air is a bit more stable, the day doesn’t really get going until noon and by then it is likely too late to finish such a long flight. So what you need is a day that kicks off early but doesn’t blow up, at least not everywhere. Some localized overdevelopment is ok, provided that the clouds cycle and thermals start up again.

Wind is also an important consideration. E.g., if the jet stream dips south into Colorado, the wind often gets so strong that thermals are broken and it’s hard to achieve good speeds; especially if you must deviate from energy lines that the wind helps create (i.e., wave, convergence, and ridge lift). Really big flights, especially triangles, require relatively mellow wind conditions.

Forecast Conditions for June 4

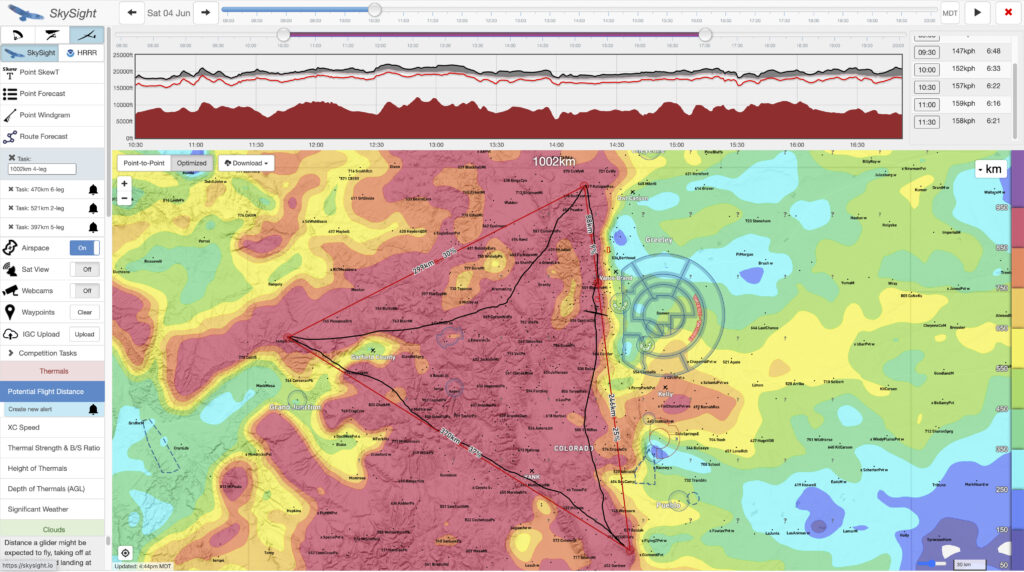

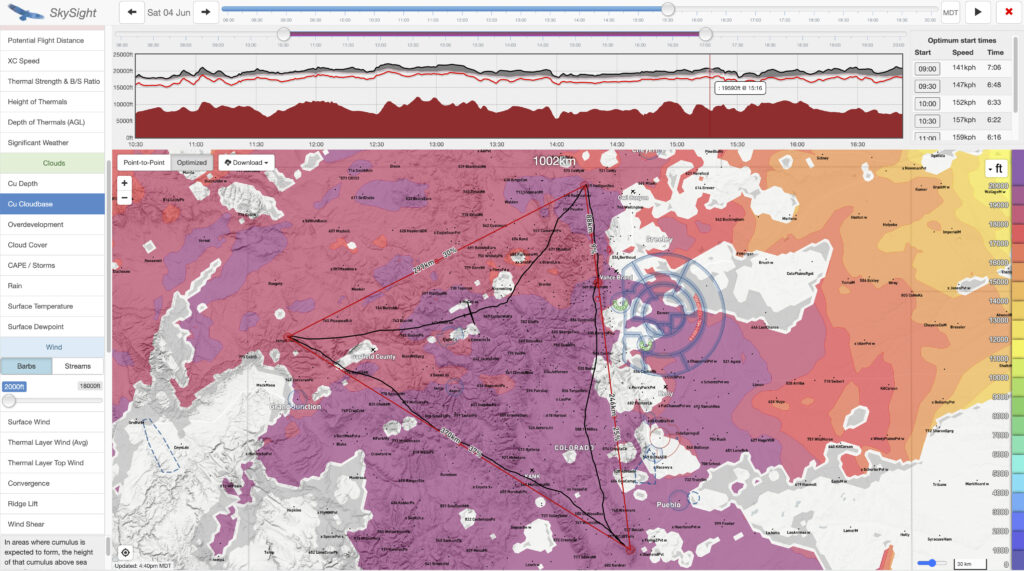

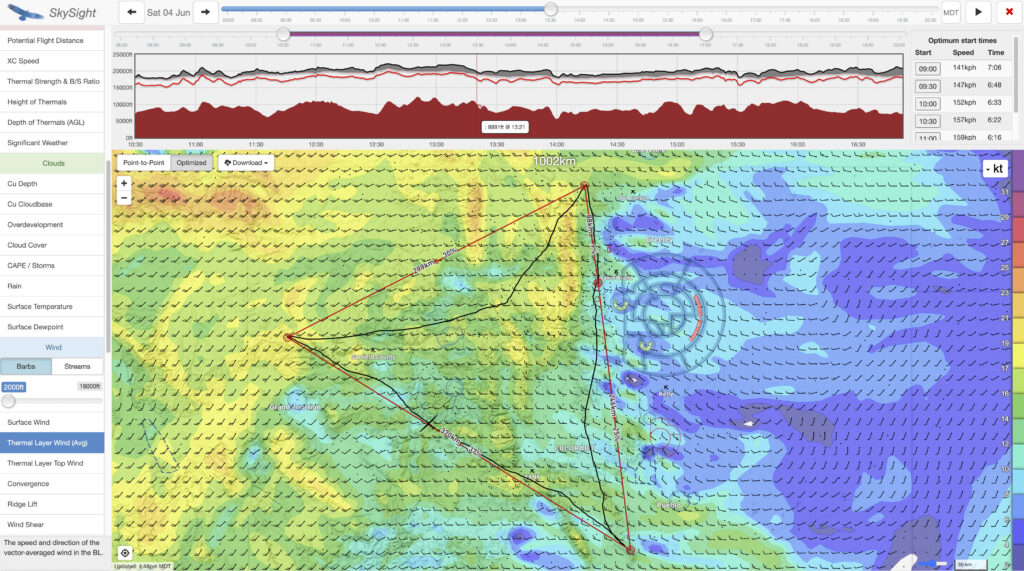

The Skysight forecast for June 4 promised the potential for such an exceptional day.

The PFD Chart was dark red all across the Colorado Rocky Mountains. That’s a promising indicator that very long flights are attainable. However, Skysight can be a bit optimistic at times, e.g. when the cloud bases are too low to fly fast and safe, so it’s important to look at the specific parameters. You want to know what it is that makes the day so good, and what pitfalls, if any, may exist.

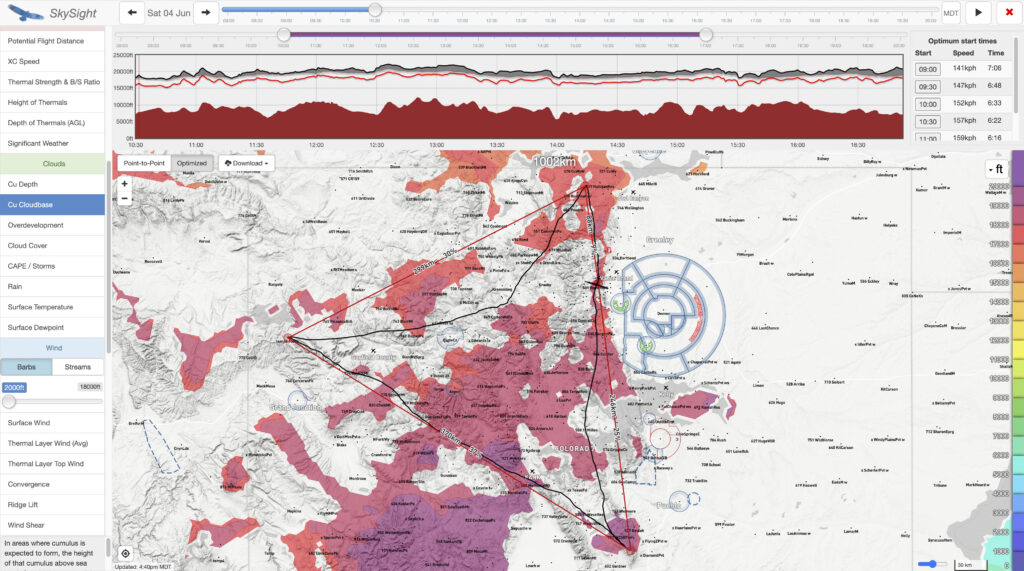

Cumulus clouds would start to pop as early as 10 am and bases would immediately be around 17,000 ft. That’s excellent to get an early start.

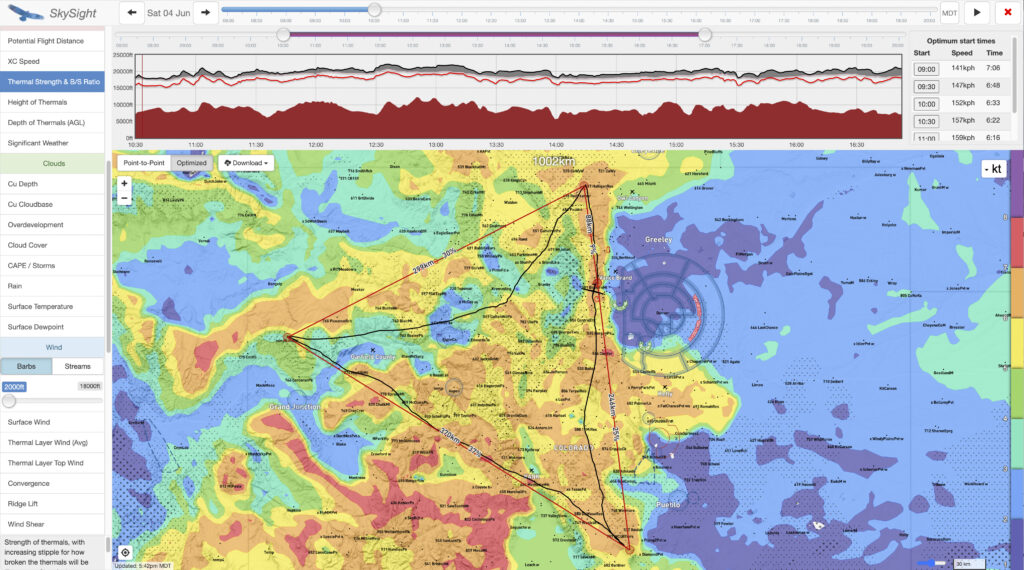

At the same time (around 10:30am) 5 to 7 kt thermals could already be expected.

By 3:30 PM, cumulus clouds with bases of 19,000 – 20,000 feet would extend across the entire task area.

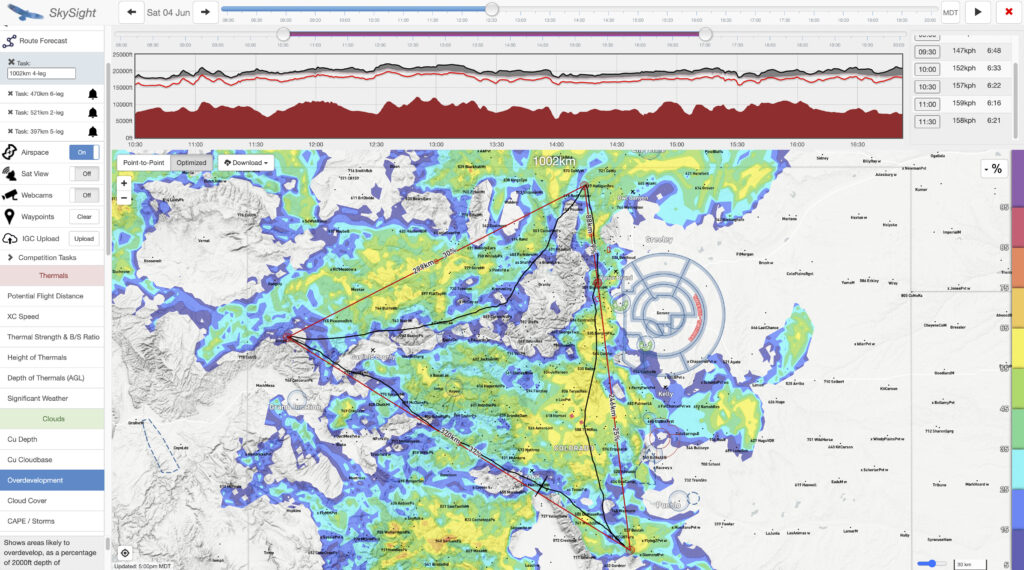

The OD Chart suggested that the southern Front Range and South Park might overdevelop early. If this is the case, it can be tricky to come back to Boulder from the south late in the day.

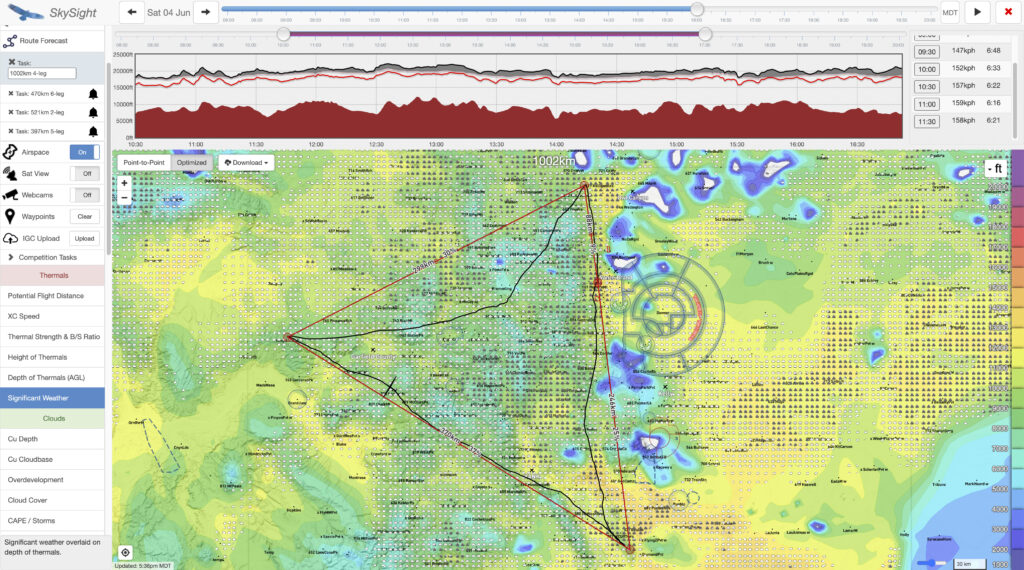

This was also confirmed by the Significant Weather Chart for 4PM, which suggested that South Park would be overcast under spread-out cumulus by late afternoon. Fortunately, there was no indication of thunderstorms on this chart.

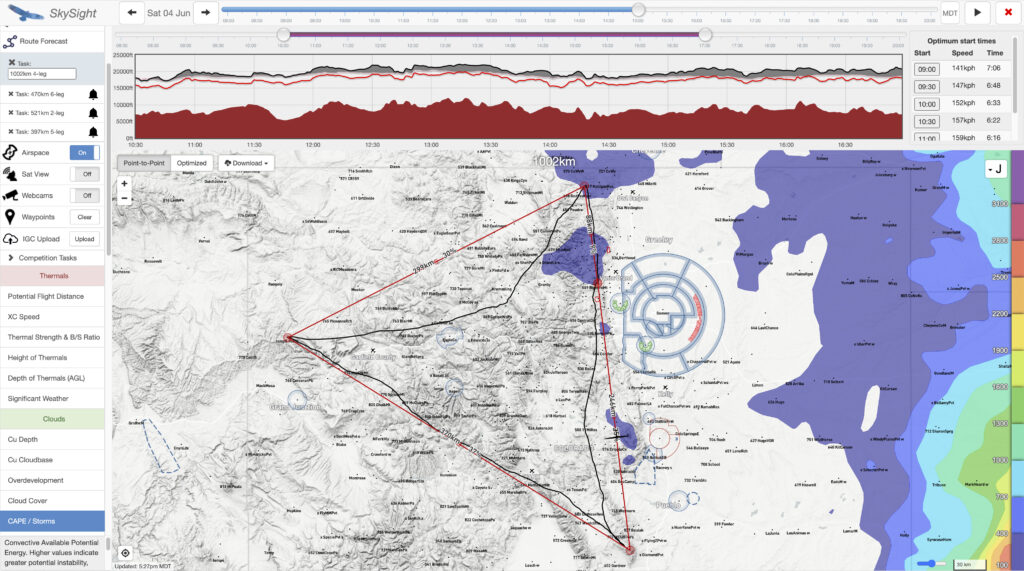

The CAPE (Convective Available Potential Energy) Chart did also not indicate a significant risk of thunderstorms, except for a few blue spots along the Front Range. In our mountainous area you want this chart to be completely blank as any CAPE index values above 100 Joule suggest a potential for storms. My interpretation from this chart was that there would be a likelihood of isolated storms that it would be possible to navigate around.

The winds in the boundary layer were forecast to be modest, especially on my second leg into the wind. They would increase a little later in the day but by then I hoped to be on my third leg and benefit from a tail wind.

Thermal strength would peak at 1PM and begin to weaken by 3:30PM. That seemed a bit early. and I did not give it too much thought. I should have examined the reasons for this more closely (we’ll get to that later). 3:30PM is often the very best part of the day.

My main conclusions from this forecast were:

-

- An early start would be possible. I booked at tow for 10AM – about one hour earlier than usual for Boulder.

- There would be nice cumulus clouds across the entire task area when I needed them. Cloud bases would start high and remain high, allowing climbs to the legal maximum below 18,000 ft.

- There would likely be overdevelopment with virga and isolated storms in parts of the task area. The biggest concern was to the south of Boulder. It would therefore be good to go south first and then avoid that area later in the day.

- Thermal strengths would be good, although diminishing somewhat early, which seemed a bit surprising. The day was forecast to remain soarable until 6PM. By then it would be good to be on final glide.

Task Planning Considerations

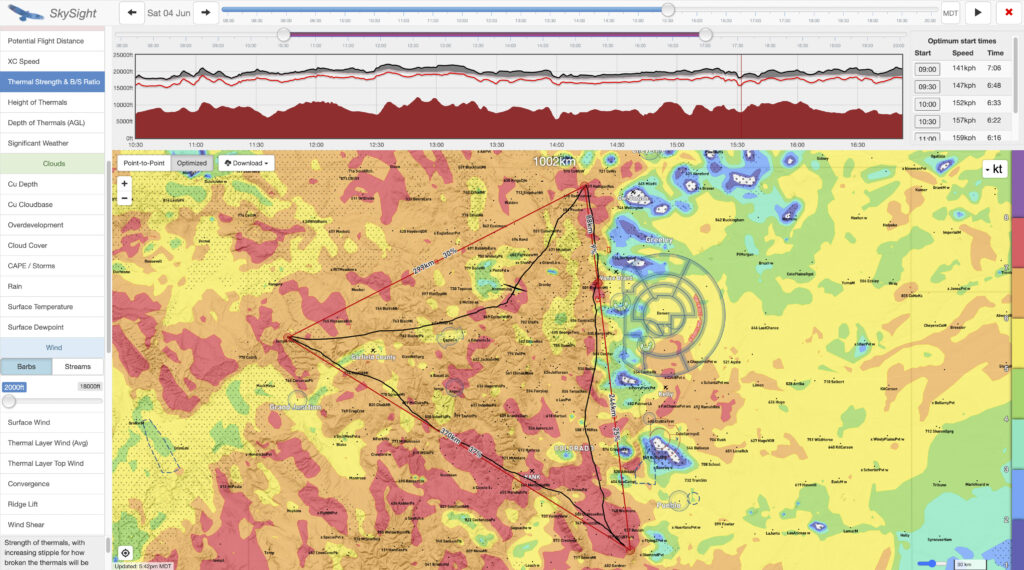

When I pre-declare a task I try to design a route that makes the best use of the forecast soaring weather.

Initially I considered declaring a 1000 km border-to-border task (from Boulder to New Mexico, then to Wyoming, and back to Boulder via a third turnpoint south of Boulder). However, the forecast early over-development to the south hinted at potential problems on the northbound leg.

I was particularly intrigued by the projected cumulus conditions to the west up to the Utah border. This area is often too dry for cumulus clouds to develop. I have never flown that far west and don’t like to fly in blue conditions so far from home, especially in an area where I have no experience. The forecast presence of cumulus in that area in early to mid afternoon made me consider a big triangle.

Having set my sights onto a 1000 km FAI triangle I had to make some key decisions.

-

- First, I wanted my start and finish point to be on one of the legs of the triangle, and not on a corner. This makes it easier to return home if you run out of time before getting to the last turn point.

- Second, I knew I wanted to go south first, because that area was projected to over-develop early. I expected soaring conditions there to be quite good before the over-development would set in.

- Third, I wanted to select a western turnpoint in an area with reliable cumulus clouds. I also wanted to construct it so that my flight path could remain over high terrain as much as possible, minimizing any stretch over potentially blue areas (such as when crossing the Colorado River Valley). Furthermore, I wanted to ensure that my third leg would be as unproblematic as possible, e.g. avoiding areas of significant forecast overdevelopment.

- Fourth, I wanted my last turnpoint to the north of Boulder in an area along the typical late-afternoon energy line over the Poudre. It would have to be in glide range of good landing places, and ideally within glide range of Boulder. Plus it needed to be selected such that there would be a more or less straight line between that last turnpoint and the first turnpoint (to make the task a nice triangle and minimize any unnecessary detours).

The Task

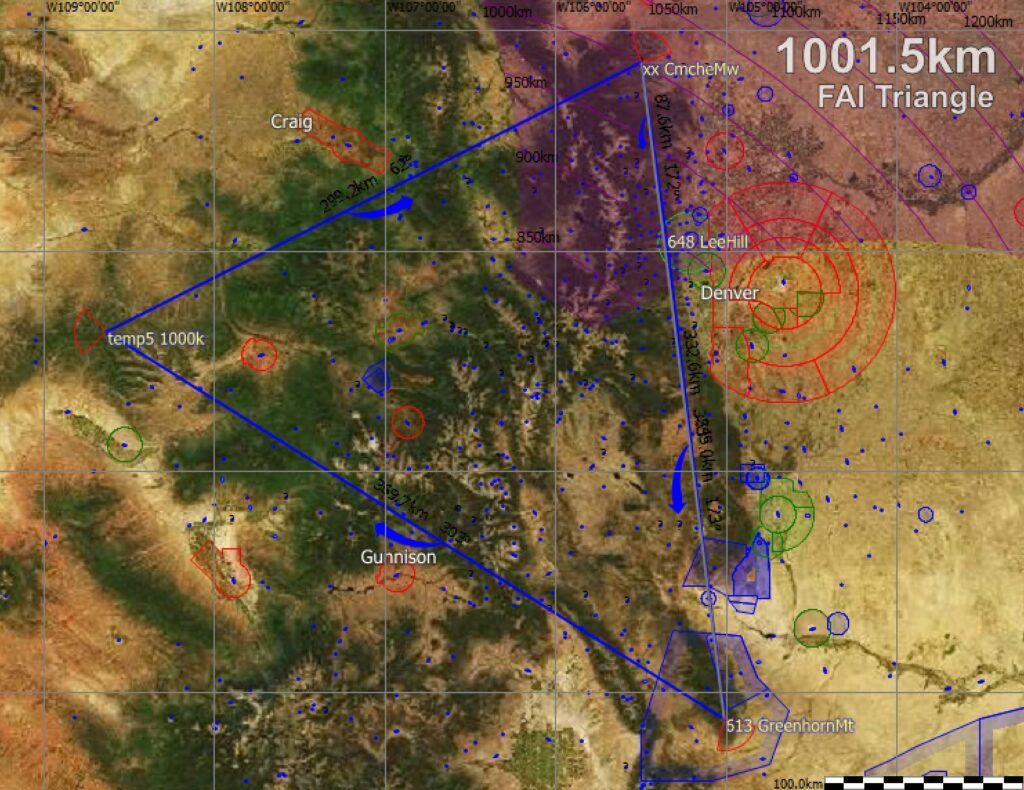

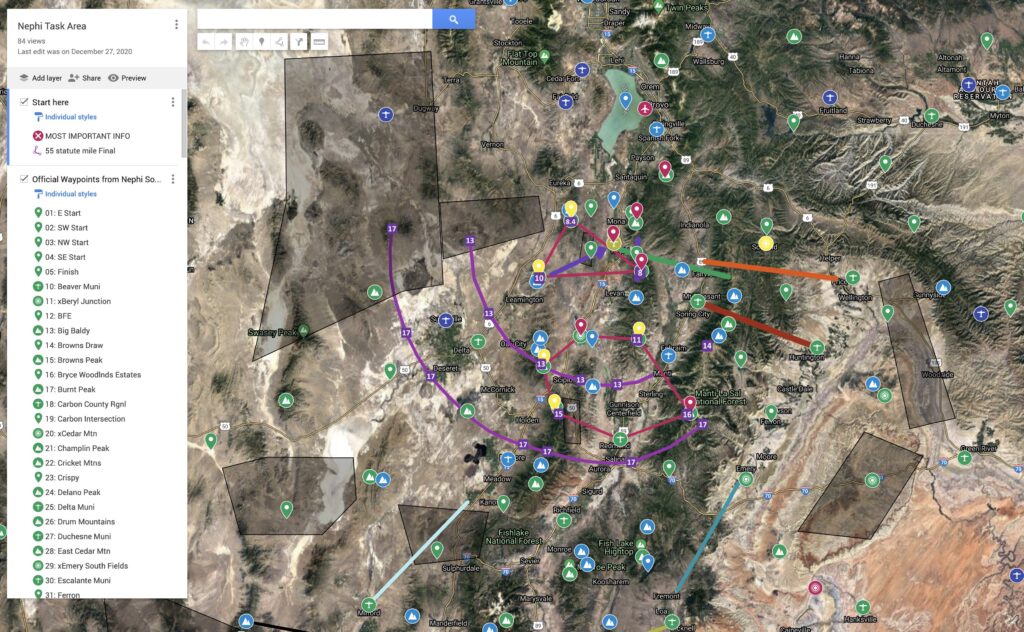

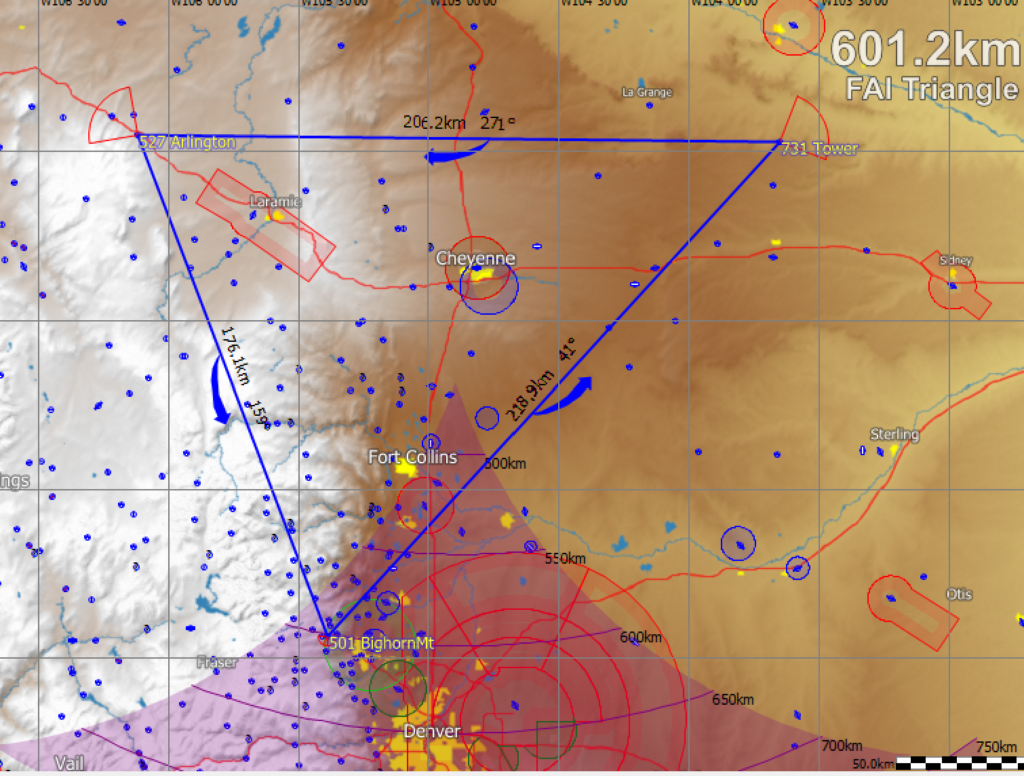

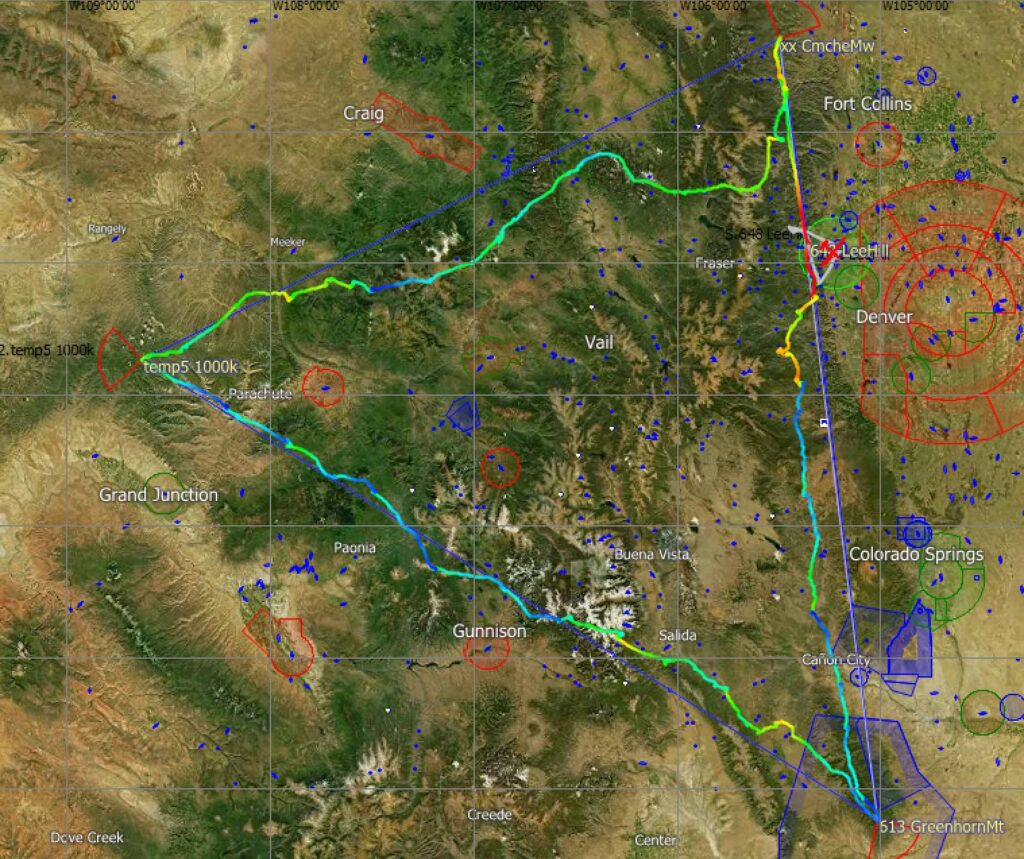

With these considerations in mind I declared a task with the following turnpoints:

-

- Start/Finish: Lee Hill. Lee Hill was likely a little further east than the first morning thermals but I did not want to pick a finish deep into the foothills that I may have difficulty to reach on final glide. Finishing just at the top of Lee Hill gives me appropriate altitude for a save arrival and landing in Boulder.

- TP1: Greenhorn Mountain. I picked this point at the southern tip of the Wet Mountains as my first turnpoint because it was the furthest point to the SSE that I thought could be reached below cumulus clouds early in the day. Often there is a big blue gap between South Park and the Wet Mountains and the forecast suggested that this area would not be an issue. Greenhorn Mountain is also ideal because a straight line drawn from there via Lee Hill is optimally aligned with the energy line over the Poudre late in the day – so the last turnpoint can be placed directly on that line.

- TP3: Comanche Meadow. Next, I picked my third turnpoint (rather than the second turnpoint) and placed it near Red Feather Lakes on the line mentioned in the bullet above.

- TP2: North of Grand Junction. Finally, I selected a western turnpoint as TP2 that would make my triangle just a bit bigger than 1000km. It was important to pick a point where cumulus clouds were forecast at my projected time of rounding it.

Timing

Skysight’s route planning tool has better pilots in mind than I am. I am almost always 15-25% slower than Skysight projects possible. E.g., for June 4, Skysight projected an average task speed of 157 kph (99 mph). There may be pilots that can fly that fast but I am not one of them. I thought an average speed of 125 kph would be more realistic for me. (My average speed on OLC for the current year to date is 122 kph).

I had booked my tow at 10:00AM and expected my start at 10:30AM. This would give me the following expected times at each of my turnpoints:

-

- TP1 Greenhorn Mountain (KM 246) : approx. 12:30PM

- TP2 North of Grand Junction (KM 616): approx. 3:30PM

- TP3 Near Red Feather Lakes (KM915): approx. 5:50PM

- Finish: Lee Hill (KM 1002): approx. 6:30PM

The exercise of estimating the average task speed and turn point times is important. It allows me to determine if my task is realistically achievable. It also enables me to compare my actual speed against the forecast and helps me decide during the flight if I should give up on the task early to reduce the risk of a land-out late in the day, possibly still far away from home.

Cut Off Time: I also resolved that I would turn back early if I would not be able to reach my westerns turn-point before 4:00PM.

Probabilities and Beliefs

When attempting these challenges you have to believe that it can be done. And I did. However, I am also realistic. No-one had ever completed a declared 1000 km FAI triangle. And I’m told it’s not for a lack of trying.

Also, I recalled that it had taken me 6 attempts to finish Diamond Distance, and it had taken me 8 attempts to finish my 750km Diplome. What were the odds that I would finish a 1000 km FAI triangle on my first attempt?

The evening before the flight I talked to one of Boulder’s most experienced XC pilots about my plans. He pointed to the recent rains in Colorado and thought the ground was too wet and Skysight was far too optimistic. His advice was, “wait until it has dried up.” “Skysight doesn’t take the recent rains into account.”

I wasn’t so sure. How could he know what Skysight does or doesn’t take into account? Of course Skysight isn’t always right. But if the day was as good as projected and I hadn’t tried, I would surely regret it. There are probably only a few days each year when such a flight can be achieved. So I made the calculated decision to ignore the advice I was given.

When fellow club members asked me in the morning what I thought the odds of completion were, I said, “about 20%”. “But that’s no reason not to try. If I don’t make the attempt, the odds are exactly zero.”

Execution

Reality never matches one’s plan exactly and at the end it all comes down to execution. In this, soaring is not very different from business or other aspect of life where the best laid plan fall by the wayside when the first curve ball is thrown your way. However, we can always learn from comparing plans and reality and figure out what we can do to improve; in planning as well as in execution. So here is my review.

The Start

I launched at 9:53am, a few minutes earlier than planned. It would have been better to take off even earlier, around 9:30am, perhaps even sooner.

The valley was inverted and I towed all the way to the first clouds. The tow was probably higher than necessary but I didn’t want to risk wasting time, or worse, falling out.

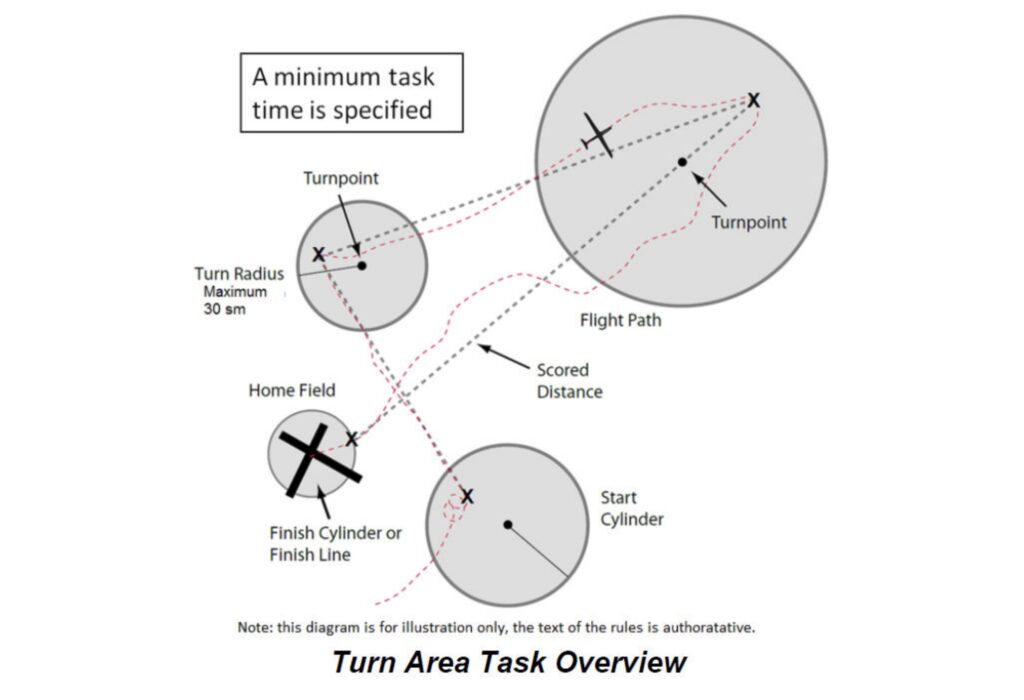

I crossed the Start Line at Lee Hill at 10:15AM, 15 minutes ahead of schedule, at an altitude of 11,400 ft. The start altitude was a strategic decision: Lee Hill is at about 7800 ft MSL. The FAI task rules say that the finish cannot be more than 1000m (3,280 ft) below the start altitude. A start at 11,400 meant I had to arrive above Lee Hill at a minimum altitude of ~8,100 MSL, i.e. ~300 AGL, for a valid finish.

Had I climbed up high before crossing the start, I would also have to finish higher and that can be a problem at the end of the day when the thermals are dying. It’s therefore best to start relatively low so this won’t be an issue later on. However, I also didn’t want to take any risk of falling out after crossing the start line. It’s a tricky equation but I think I got it about right.

First Leg to Greenhorn Mountain – 246 km

After crossing the start I was in search of a strong climb that could take me up toward cloud base.

I did not want to settle for 4-5 kts because it would take well over 10 minutes to climb up to cloud base. As a result, I stayed lower for much longer than I wanted as I struggled to connect.

I joined TR in a great 10kt climb over Black Mountain (ESE of Mt Evans). Finally I got up to 17,500 ft in no time.

A few minutes later I caught up with TR, a club Discus piloted by Jason Ely who was finding great lift lines. I was quite impressed by his route choices.

Convergence-enhanced thermals over the foothills of the southern Front Range. Good lift along the western edge of these clouds.

Reliable clouds make for fun, uneventful, flying.

I tanked up over the 39 Mile Volcanic Field west of Victor before heading out across a blue hole towards the Wet Mountains in the center ahead. It’s a significant gap but not a big deal for my 18m Ventus 2 cxT.

Nice clouds over the Wet Mountains propelled me towards my first turn point at Greenhorn Mountain.

I’m taking a powerful climb before turning Greenhorn Mountain.

I rounded Greenhorn Mountain at 12:22 PM. 246 km, about 1/4 of the total distance, is done. My average speed on the first leg was a little slower than the overall estimate of 125 kph but I was still 8 minutes ahead of my estimated schedule. I hoped the second leg would go a bit faster given that I was getting to the strongest part of the day.

Second Leg: Greenhorn Mountain to North of Grand Junction – 370 km

Soon after turning Greenhorn Mountain, and heading north-west, I crossed paths with BC and XR who were aiming for the Colorado – New Mexico border. (Unfortunately both got caught in OD on their return leg to the north. They made it back to Boulder but were not able to get to Wyoming.)

The clouds over the Wet Valley were not working nearly as well as those over the mountains .

I got much lower than I would have liked. These situations can become a big time drain unless one is able to find a good climb.

I had to take a little detour and finally found a reasonable climb in the lee of the Sangre de Cristos.

At 1:15 PM I am above Salida. I know this area well from SSB soaring camps.

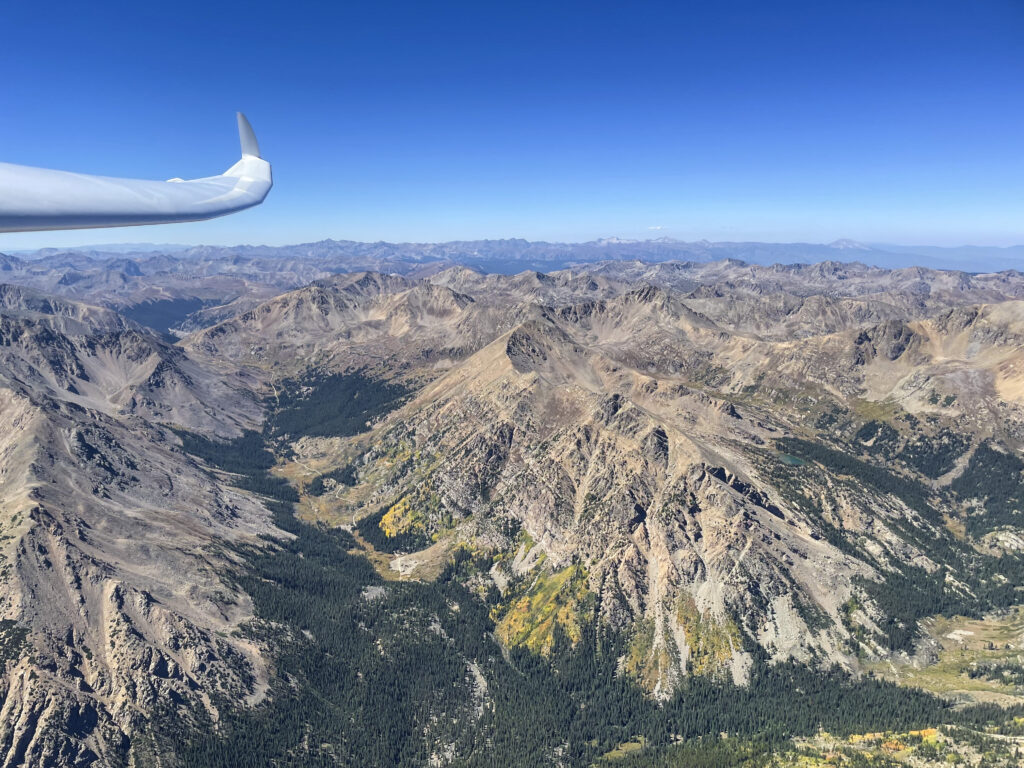

There is a big blue hole west of Salida towards Monarch Pass. The wind has shifted and is now blowing pretty hard out of the north-west, directly where I need to go. This means I have to approach Monarch Pass from the lee side and the transition into the Gunnison Valley is likely to be tricky. I am taking a climb to 15,700 ft – as high as I get get – before pushing on.

The transition ahead is the trickiest part on the second leg. I anticipate significant sink before getting to Monarch Pass and will need to find another climb to get across. The sky is not overly promising.

I arrive below a rotor cloud on the flank of Mount Shavano at 12,600 ft, about 1,600 ft below the peak. I’m hoping the rotor works. If not, I have to turn back several miles where I should find a climb over the Arkansas Valley north of the Salida airport.

The rotor is quite rough. It wants to roll the glider this way and that way and I have to use full control deflections to keep myself centered. I work hard for 8 minutes to regain 3,500 ft, enough to press on.

Things look better at 16,000 feet. There are good looking clouds on the other side of these mountains.

It is 1:45PM when the first virga of the day appear. But there is no significant vertical development in any of the clouds and I am confident the clouds will just cycle. This likely means some virga dodging but hopefully continued good thermal conditions. Also, as I get further west, and closer to the Utah desert, the air should become dryer. And for now it’s too early to worry about the third leg. I still have more than 200 km to go before TP2…

It’s typical for overdevelopment and virga to concentrate over the mountains while the wider valleys – such as the Gunnison Valley to the left – remain much dryer. The lift is quite good here on the southern side of the clouds, often up to the edge of the virga.

In a few minutes I will get to an area where I have never flown before. I take out my map to better visualize my landing opportunities beyond Crested Butte. There are a number of good choices but it’s important to know where they are relative to the terrain. And it’s always good to visualize this while you’re so high that you’re relaxed and the stress level is very low.

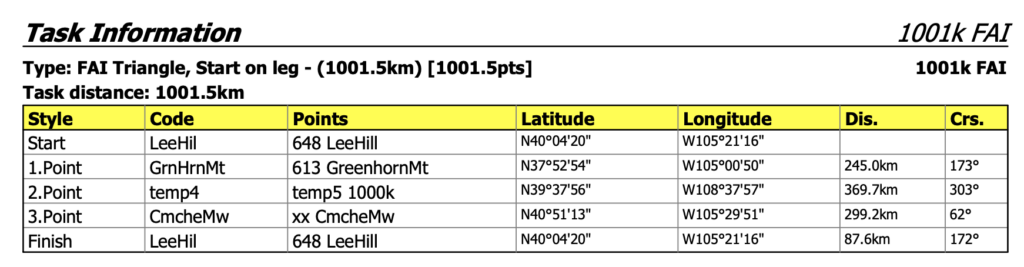

Crested Butte is a magical place. A few years ago I ran one of the prettiest ultramarathons in this area. Seeing the valley from the cockpit is even more magnificent.

The West Elk Mountains will be the last big mountains for a while. The clouds ahead look quite promising. Also, as expected, the air does look a bit dryer as I continue northwest.

I make good progress in this area and continue to enjoy the scenery. The clouds work well and are reliable. There are also plenty of landing options in the valley to the left.

As I leave the tall peaks behind, mountains give way to rolling hills. The sky keeps getting dryer but there is no shortage of nice cumulus clouds. I continue my flight with confidence.

The clouds in this area are cycling and conditions are a little soft for a while. But there’s no doubt – for now – that there is good lift ahead. I have the airports of Glenwood Springs and Garfield County in glide.

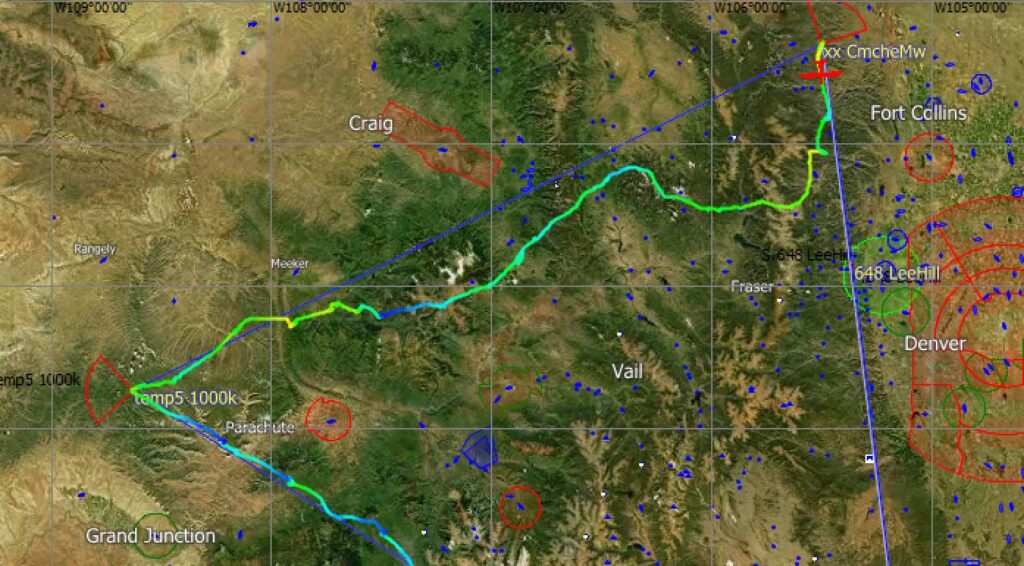

The Colorado River Valley comes in sight as I approach Haystack Mountain. I am relieved to see that there are clouds on the north side of the valley. I will have to cross the valley and then continue to head west to get to TP2.

I am tanking up above Haystack Mountain before the Colorado River crossing.

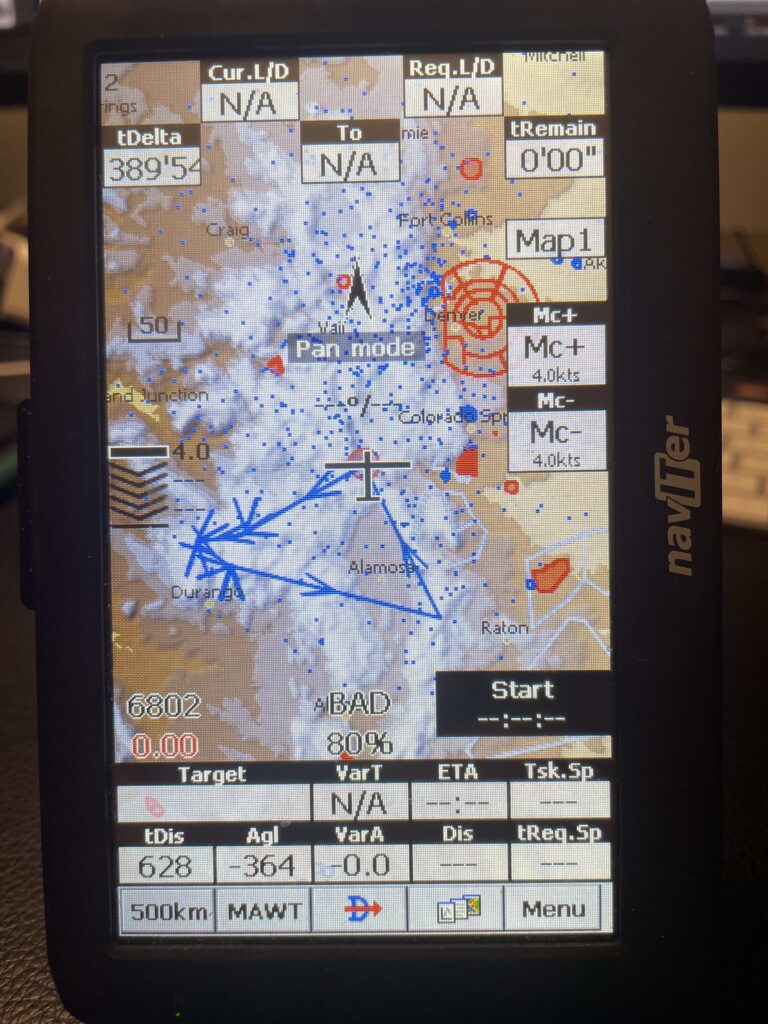

It is now apparent that the clouds are much sparser on the north side of the Colorado River Valley. The air is also more hazy, indicative of a different and potentially weaker, airmass. I have 70 km to go to get to my second turnpoint straight ahead. Can it be done? I’m not sure but I’m definitely willing to try.

There are still clouds ahead as I get to the north of the Colorado River. But I also start to notice the cirrus layer in the distance and wonder if my turnpoint may be in the shade.

I am excited that my first climb after the valley crossing averages 8 knots to 17,500 ft. When you’re flying into a different airmass there is always some uncertainty how things will go. Well, this climb is promising.

It is 3:15 PM and I have another 36 km to go to my second turnpoint. The clouds don’t look great but I anticipate that they will work: when the air is so dry, even small wisps can indicate powerful climbs. In particular, I am on the lookout for any indication of new clouds that may be emerging. That’s where the best lift is usually found.

As I approach TP2 it has become obvious that the cirrus layer overhead is rapidly moving eastwards. The ground below is already shaded and I have not found a good climb in more than 10 minutes. I am now down to 14,000 feet and eager to get the turn behind me and back into the sun.

I turn TP2 at 3:27 PM, 3 minutes ahead of my schedule. I find that quite remarkable. My second leg of 370 km took me just 5 minutes longer than my estimate. If commercial airlines would deliver that level of precision, I would be quite pleased. 🙂

Third Leg: North of Grand Junction to Comanche Meadow (NE of Red Feather Lakes) – 299 km

Starting out on my third leg I have two goals: find a good climb to get back to altitude; and get back into the sun and out from the cirrus overcast.

There are beautiful clouds below a beautiful blue sky in the distance. Lets get there!

I found some mediocre climbs under some wisps below the cirrus layer and I’m now considering two routing alternatives. I had planned to follow the Colorado river along the north rim but there are good-looking clouds 20 degrees to the left in the direction of Meeker. Since I am not familiar with that area I review it again on the map to ensure I have good landing options along the way.

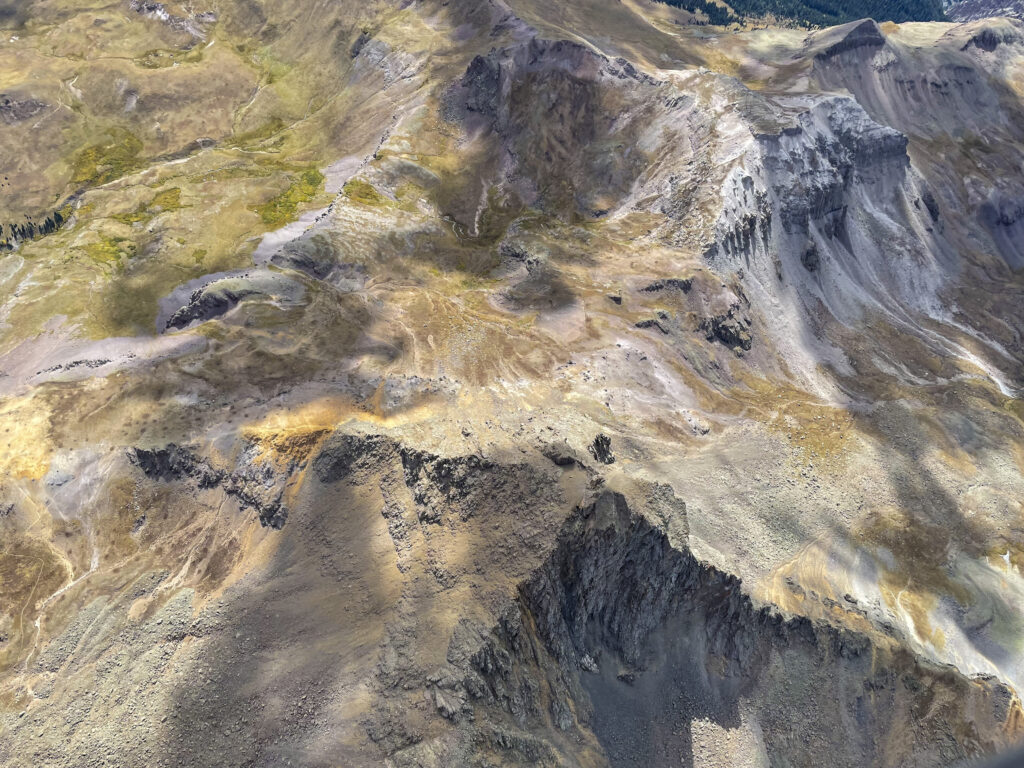

I decide to head for the promising looking clouds toward Meeker. The labyrinth of canyons below is fascinating. It would also be a sure way to get lost. So let’s stay high…

The problem: once I get to the promising clouds, the cirrus layer has moved east as well and the clouds are decaying – promising no more. I had expected an 8-10 kt climb. Instead I only find three knots. I only make three turns, then push on towards the sun.

There are more great looking clouds ahead under a pretty blue sky. The airport of Meeker is in the White River Valley to the left and in easy glide range.

As I approach the clouds, they have started to fall apart. The cirrus layer has advanced as well and is shading the ground below.

I spend 6 minutes in a mediocre climb. Not because I want to but because I have to. I gain only 1700 ft – a rate of less than 300 fpm – then I press on to outrace the cirrus!

After all: there are very appealing clouds ahead, under a gorgeous blue sky towards the Flat Tops.

But when I get there… same story: the cirrus layer has caught up once again. I am still determined to win this race though. I can feel that my entire task is hanging in the balance. If I can’t outrace the overcast I will be too slow. Or worse, the lift may die altogether and I may be forced to land – far away from home. It takes 4 1/2 hours to drive from Boulder to Meeker. I really don’t want to land here!

Aren’t there great looking clouds over the Flat Tops Mountains to the east? And the sky is blue!

But when I get there … oh my this is frustrating!

OK, I have to get to THAT cloud. It is very pretty indeed. And the sky is so blue!

But when I get there? You guessed it – the cirrus layer has just moved in. But: the cloud is still working!!! I climb 4,300 feet in 7 minutes, an average of 615 fpm, and I get back to 17,700 ft.

There is still hope! So let’s use the height and outrace that cirrus for good!

Doesn’t the sky look great! But I cannot allow myself to make any mistakes. The cirrus is moving fast. I have to stay ahead of it but I also can’t afford to get low. I can’t recall a glider race that felt so intense. In a glider race your opponent may overtake you but that is it. This opponent is different: if you don’t stay ahead you get taken out of the race altogether!

I made it across the Flat Tops and am heading towards Toponas. This was my most westerly turn point during my Diamond Distance flight three years ago. This is the point where the Continental Divide comes back into view on the horizon. And if the sky ahead looks like this then getting back to Boulder definitely seems doable. Maybe even the completion of the task? I briefly wonder but then decide to ignore this unhelpful thought. Don’t count the chicken until they hatch… I still have to focus on outracing the cirrus. I know it’s not far behind.

Here’s proof: as I circle below a dark cloud east of Toponas I can see how much the cirrus has advanced as well. The Flat Tops that had just been in the sun 10 minutes ago are already in shade and the clouds above look like they are falling apart. Every minute does still count! For now there is still sun on the ground directly below. Let’s concentrate on climbing well so I can keep it that way!

I stay north of Kremmling above the high ground and head towards the Rabbit Ears Range. There are some pretty clouds along the north side, most likely the result of a typical convergence line in this area, virga to the south.

As I arrive over the Rabbit Ears, the sky has become more complicated. The clouds ahead are dissolving, there is virga to my right, and I have to be careful not to be caught in a down-cycle. Plus, with the cirrus not far behind, I really can’t afford to get stuck!

There is a tricky decision to be made here. My third turnpoint is 85 km to the NE. The direct route to get there is to the left of the nose via North Park, flying under the dark clouds in-between the virga lines. It is works, that would be the shortest path. If it doesn’t work I would get stuck in North Park. I might be able to make it to Walden or have to land in a field. The alternative is to veer to the right and detour around the virga on the south side. This route is more familiar to me, gets me closer to Boulder, and probably makes it easier to cross the Continental Divide. If it doesn’t work I would land at the airport in Granby.

I opt for the detour and to go around the clouds on the sunny side. The probability of finding lift here seems higher to me and the risk of getting caught in virga and rain much lower. It’s also the closest route across the divide and I still worry about the cirrus catching up with me from behind.

Some snow falls outside as I work my way around the cloud into the sun. I quickly close my vents – otherwise snow makes it into the cockpit.

The Continental Divide is along the horizon, 40 km ahead. Getting over these mountains is my next challenge. If successful, I will have Boulder in glide and can assess the odds of making it to my last turn point. There are some clouds ahead, so I am hopeful that it will work.

The clouds that just looked so nice 3 minutes ago have started to fall apart. But there is still sun on the ground so there ought to be a climb somewhere. I will need to gain two or three thousand feet to make it safely across the Divide.

I try every climb I can find. The wind is favorable, drifting me in the direction I need to go. So even a slow climb is ok. I can’t be too choosey now. Provided that I stay ahead of the cirrus!

Looking back to the west where I came from it is apparent that my return from turn point 2 has truly been “just in time”. Had I turned TP2 only 10 minutes later I very much doubt that I would have made it.

I didn’t get much of a climb. 14,700 ft with 25 km to go to cross a 12,200 ft pass is not a recipe for success. I will need another climb. The clouds don’t look great but I still believe that it will work.

I am at 14,100 ft. The ridge ahead is at about 12,200 ft. Not a lot of margin, but I find myself in good air with a tailwind and I am pretty confident that I can make it safely across. Parallax is the best way to gauge the likelihood of success: if more terrain beyond the ridge becomes visible I should be high enough. If that isn’t the case I will have to find another climb first. The good thing here is that I can always turn around and have a save glide to the Granby airport if necessary.

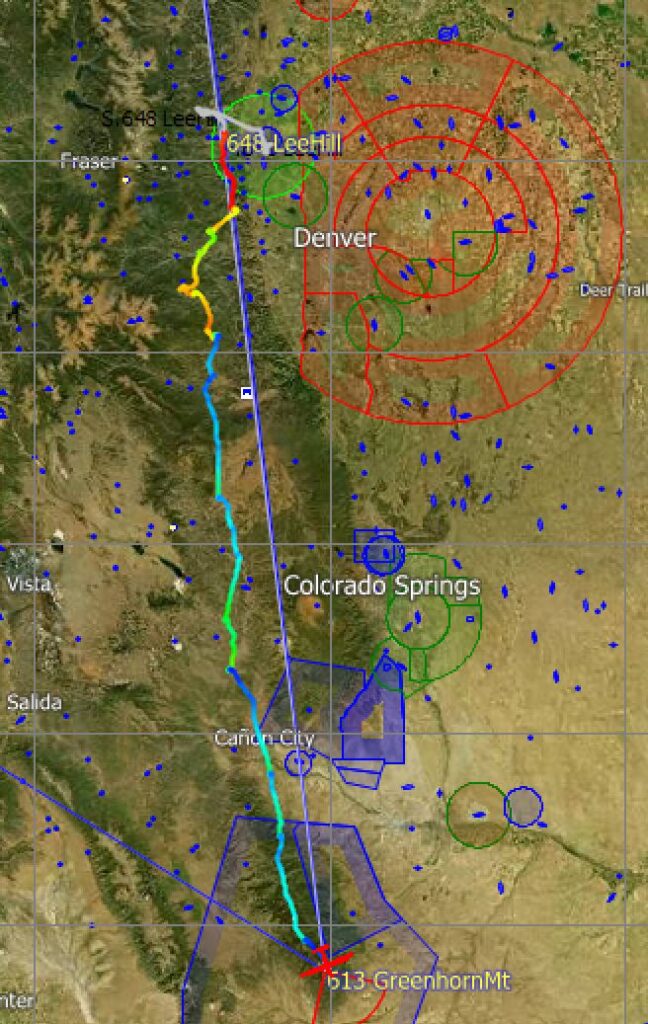

I am directly over the divide and trying to find a climb. I now have Boulder in glide (although somewhat marginal) but I am looking for more altitude to see if I can make it to TP3.

Near Longs Peak I manage to climb to 14,000 ft and decide to start heading towards TP3, 62 km ahead. The sky is not looking great but I am not ready to give up. There is often an energy line in this direction and the western edge of the clouds should mark its location. There are also often good climbs late in the day above the ridges ahead. I definitely have to give it a try!

Indeed. I find a climb north of Estes Park above the ridge leading to Mt. Dickinson. As I climb through 15,000 feet I notice the absence of the familiar pulses from the oxygen system. I started the day with 1300 PSI in my oxygen tank but more than 8 hours at altitude must have depleted it. Oh no! This is really unfortunate because late in the day it is often critical to stay in close connection with the clouds. I am not one to risk hypoxia and decide to leave the climb early. It means I will have to bounce along well below cloud base and find evening climbs that still emanate from the ground.

The clouds ahead look pretty good and I’m hoping to find good air along the way as I continue towards TP3. There is often a convergence line in this area. A glance on my flight computer shows that Skysight is predicting such a line some 15km further east. But looking at the clouds I think it is more aligned with the course I’m following.

The line did work reasonably well. I am now approaching the final turnpoint. There is some virga ahead and I wonder if I have to fly into it to get my turn. There is always some uncertainty when approaching virga. Sometimes there can be strong sink but that is not a given. It’s even possible to find strong lift and rapidly climb while flying through rain or snow. As I look ahead it’s hard to tell what I will find. But even if I find strong sink, I have enough altitude to escape towards Christman Field at the base of the hills to my right. With a good plan B in place I head into the turn.

There’s neither lift nor significant sink as I turn TP3 at 6:07 PM, now 17 minutes behind schedule. The last leg took 20 minutes longer than I had anticipated, the consequence of weak thermals while I tried to outrace the overcast, plus the significant detour around the virga over the Rabbit Ears Range. But at this point the schedule is irrelevant. Getting to the finish and safely landing before sunset is all that matters.

Final Leg: Comanche Meadow to Lee Hill – 88 km

When I planned the flight I had hoped to be above 17,000 feet and within Final Glide upon my last turn. But as things stand, I still have some climbing to do.

Looking ahead after turning TP3 I have 88 km to go to the finish. There is still sun on the ground over the Poudre Canyon ahead to my left. However, I decide not to take the most direct line. Instead, I retrace my flight path to get back to the west side of the clouds ahead. I expect to find the best air along that line. It is quite beneficial for the last leg to be in an area that I know well.

I am delighted that there is still sun over the Poudre Canyon ahead. I have often found late afternoon thermals in this area. However, more often than not I am flying much higher in this area than today. I have 80 km to go to the Finish Line and my flight computer shows that I am about 3,500 ft below final glide for my task at MC4. Beyond the Poudre the sky looks completely overcast so I HAVE to find some lift in this area.

Lucky again! I find my last climb of the day directly over the Poudre Canyon with 59km to go. My flight computer shows that I just made Final Glide altitude! That’s a big moment!

The sky is completely overcast but I am now 900 ft above Final Glide at MC4 and I am confident that I have made it. Wow! I’d like to let that sink in, but I am also aware that I still have an airplane to fly to a finish and a safe landing. So let’s stay focused on that!

8 hours and 30 minutes after I flew across the Start Line above Lee Hill setting out on a flight across mountainous Colorado, I have returned to the same spot. It is hard to believe. I have completed my 1000 km FAI triangle. The first ever in Colorado. The time is 6:46PM, 16 minutes later than I had planned. My average task speed was 118 km per hour instead of my estimated 125. But all of that is largely irrelevant. What matters is that I got it done. Now all that’s left to do is a safe landing. I deliberately go through my checklist. Dump the water, put the gear down, check the spoilers, check the wind, look for traffic, flaps in position 2, and bring it home.

Winds are calm on the ground as I bring a successful flight to completion with a smooth landing a little over an hour before sunset.

Flight Trace and Key Stats

You can find the full .igc flight trace with all details on WeGlide and on OLC.

-

- Declared FAI Triangle Distance: 1001.5 km

- Declared Flight Distance: 1001.5 km

- OLC Flight Distance (optimized for 6 legs): 1071 km

- Task Duration: 8:30:52 hours

- Average Task Speed: 117.62 kph

- Flight Duration: 9:06:30 hours

- Circling Time: 2:08 hours (24%) – 52 Thermals, Average Climb Rate 4.4 kts

- Average Glide Ratio 67:1, Average Netto: 1.4 kts,

- Average Ground Speed in Cruise Flight: 184 km per hour

Lessons Learned

Reflecting back on the flight there are a bunch of things that I got right and also several opportunities for improvement.

Let’s start with what worked well.

-

- Relying on Skysight as my main forecasting tool worked well and the forecast was quite accurate with respect to thermal heights, presence of cumulus clouds, cloud bases, wind direction and strength, etc. There were a bit more virga cells than forecast and Boulder did see a local thunderstorm although none was predicted. I had also checked local weather forecasts for key locations along the route, largely to assess the risk of storms. But this was mostly helpful to boost my confidence. I did not learn anything that was new or different from Skysight.

- I was well prepared for the geography of the flight. I even carried a list of all airports along each leg with local radio frequencies. Having my physical soaring map in the cockpit was also very helpful. I knew the overall terrain quite well but it was super useful to better visualize the location of airports within those sections of the task area that were new to me. There was no point during the entire flight when I did not have a suitable airport within easy glide range.

- My estimated speed of 125 kph and the estimated times at each turn point were quite realistic even though I ended up flying a little bit slower. I did not trust Skysight’s attainable speed of over 150 kph and I don’t know if anyone could have flown this fast. I think 135-140 kph may have been possible for a better pilot than me but I doubt 150 or more was really achievable in an 18m glider.

- Crew for a potential landout. I had talked to ABC, one of SSB’s flight instructors and my Official Observer, and he assured me that he would be prepared to come and get me if I were to land out. I also know there are many other great members at the SSB who would do the same. Having made such arrangements in advance was not only very comforting. It ultimately proved to be essential because it allowed me to take the sporting risk of a potential landout (not a safety risk!), especially when I had to push to my westernmost turnpoint even though I could see the cirrus layer moving in.

Things I would do differently if I could do it all over again:

-

- I would launch even earlier. The first little clouds appeared by 9:15 am and I did not get off the ground until 9:53 am. Every minute counts if you have to be concerned about making it before the end of the soaring day. I left more than half an hour on the table at the beginning.

- I missed the predicted Cirrus forecast. In fact, I did not look at the high clouds forecast at all. That was clearly a mistake. I even remember that I was puzzled about the declining lift strength by 3:30PM but did not think to examine the possible reasons for it. Next time I will look. However, somehow I am glad that I didn’t because the forecasted cirrus layer might have dissuaded me from attempting the western turnpoint. And in that case, a 1000 km FAI triangle task would probably not have been possible.

- I need to add more oxygen for such long flights. I never ran out of oxygen before and I thought 1300 PSI would easily suffice. It is entirely possible that forcing myself to fly below 14,000 ft towards the end could have caused me to fall out of the working band and land out just before the end. Luckily I kept finding new climbs and eventually got on final glide. Next time I will look for a completely full bottle to fill my tank to the max.

Luck comes into play to!

-

- I did not anticipate that the cirrus layer would move so fast. Ultimately it was sheer luck that I was able to outrace it. Only after the fact did it sink in how narrowly I won that race. Had I arrived at my second turn point only 10 minutes later I am fairly certain that I would not have made it back to the Front Range.

Finally, I would like to thank Armand Charbonneau, my official observer and potential retrieve crew. I could not have done it without you. In addition, I’d like to thank everyone at SSB, in Austria, and in France who has been instrumental in coaching and mentoring me over the years. There are too many to name. You know who you are. Your advice and counsel has played a key role helping me get to the point where I was able to complete such a flight. Thank you!

Concluding Thoughts

At the beginning of this article I explained that declared 1000 km triangle flights in Colorado might not have been done before because they require exceptional days. However, exceptional days have existed before and they will continue to exist. They are probably more frequent than we might think. I am convinced that there are several days each year when such flights can be achieved.

But one thing has changed over the years: in the past, it was usually impossible to know which days were truly exceptional. The weather forecasting just wasn’t good enough. Now we’re seeing many more record breaking soaring flights in Europe, in New Zealand, in Africa, and all over the world, and it’s not (primarily) because the sailplanes have gotten better. It is also not that the pilots have become better or more ambitious. What really has become better is the weather forecasting.

Historically you could not know which parts of a task area would OD first. You could not reliably predict whether there would be cumulus clouds hundreds of miles away from home at a specific time of day. It was practically impossible to forecast how the wind speed and wind direction would evolve in different parts of a task area at different times of the day. And the position of convergence lines somewhere in the blue? Only a few years ago there was no chance of knowing.

But now we can predict all these things. Don’t get me wrong. The forecast is still only a forecast. Reality can – and is – different. There still are inaccuracies. However, these inaccuracies have drastically diminished and they will continue to diminish.

We can now plan much better that we ever could. My flight will not be the longest flight in Colorado for long. I believe we will see many more. I wish everyone attempting them the best of success.

Have fun and fly safe!