As I am preparing for my first soaring contests in 2020 I have been thinking a lot about managing risks in soaring competitions. Will I be tempted into taking risks that could threaten my safety? How can I recognize risks in advance? Are all risks bad and must be avoided? Won’t I have to take risks in order to compete? Are the winners typically those who take the greatest risks? Is it even possible to compete and stay safe?

It took me a while to sort through these questions and I may not have all the answers. But here’s an attempt at addressing them and I am satisfied that it leads to a good place.

When we talk about risks and soaring we usually refer to Safety Risks, i.e. the likelihood that a person will be harmed (injured or killed) by participating in a hazardous activity. I recently published two articles on this subject entitled “The Risk of Dying Doing What We Love” and “Does Soaring Have to Be So Dangerous?“. For obvious reasons we want to keep our safety risks as low as possible.

But, like most sports, soaring also involves another kind of risk that is best referred to as Sporting Risk. Sporting Risks should be understood as a player’s gamble in a competitive game: if the bet is successful, the player stands to gain in competition; if the bet is unsuccessful, he or she stands to lose. E.g., a tennis player who places his shots close to the lines takes the gamble that his balls will land inside the court and be difficult to return. If the gamble is successful he stands to gain the point, if the gamble is unsuccessful, he loses the point. A slalom skier who takes tight turns around the gates takes the gamble that she will ski the most direct line and round each gate correctly. If the gamble is successful she stands to win by scoring the fastest time, if her gamble is unsuccessful (i.e., if she misses only one single gate) she fails to complete the course and loses the race.

While we must keep our Safety Risks as low as possible, this is not the case for Sporting Risks: a tennis player who plays only safe shots makes himself vulnerable to attacks from his opponent, and a slalom skier who gives each gate a wide berth will be too slow to win a race. Conversely, a very high risk strategy might pay off now and then but it is unlikely to succeed in the long run: a tennis player who places every single shot close to the line will accumulate too many unforced errors, and a slalom skier who tries to round each gate within fractions of an inch will not complete enough runs. Sporting Risks must be optimized instead of minimized. The player has to find the right balance between offense and defense. A “Goldilocks” approach wins. (Watch Mikaela Shiffrin, already one of the greatest slalom skiers of all time, getting this balance perfectly right.)

Sporting Risks in Soaring

If you practice soaring as a sport, i.e. as soon as you venture beyond a safe gliding distance to your home airfield (you don’t even have to fly in a contest), you are confronted with sporting decisions and Sporting Risks. John Bird and Daniel Sazhin recently published a scientific paper that specifically proposes a (sporting) risk strategy for Thermal Soaring. A simplified version appeared in two parts in the March and April 2019 editions of Soaring Magazine.

My summarized interpretation of their work is this: when we leave a source of lift and glide out on course of a cross-country task we can never know with certainty whether we will find another thermal. If we don’t, we have to land out. Our likelihood of having to land out is a function of our sporting decisions: the course line we choose (e.g. how many clouds we sample through course deviations), our inter-thermal cruising speed, and how selective we are with respect to accepting lift. The more aggressive we fly, the greater our potential task speed, and the higher our odds (our Sporting Risk) of having to land (and failing to complete the task). John Bird and Daniel Sazhin show that our land-out risk compounds the more glides we need to complete the task because each glide is an independent event, i.e. we will be forced to land even if we fail only once to find another climb. If we fly in a multi-day contest where even one land-out can destroy our chances of performing well, our Sporting Risk compounds across all the glides needed to complete all contest tasks. To succeed, we must find the right balance: if we are too cautious we will leave points on the table; if we are too aggressive we will end in a field and blow the contest result. When conditions are strong with multiple reliable lift sources ahead we can fly fast and direct; when conditions weaken we must quickly “shift gears” and switch our focus on staying aloft. In short: we must always strive to optimize our Sporting Risks and get the risk balance just right. The Golidlocks approach wins in soaring as well.

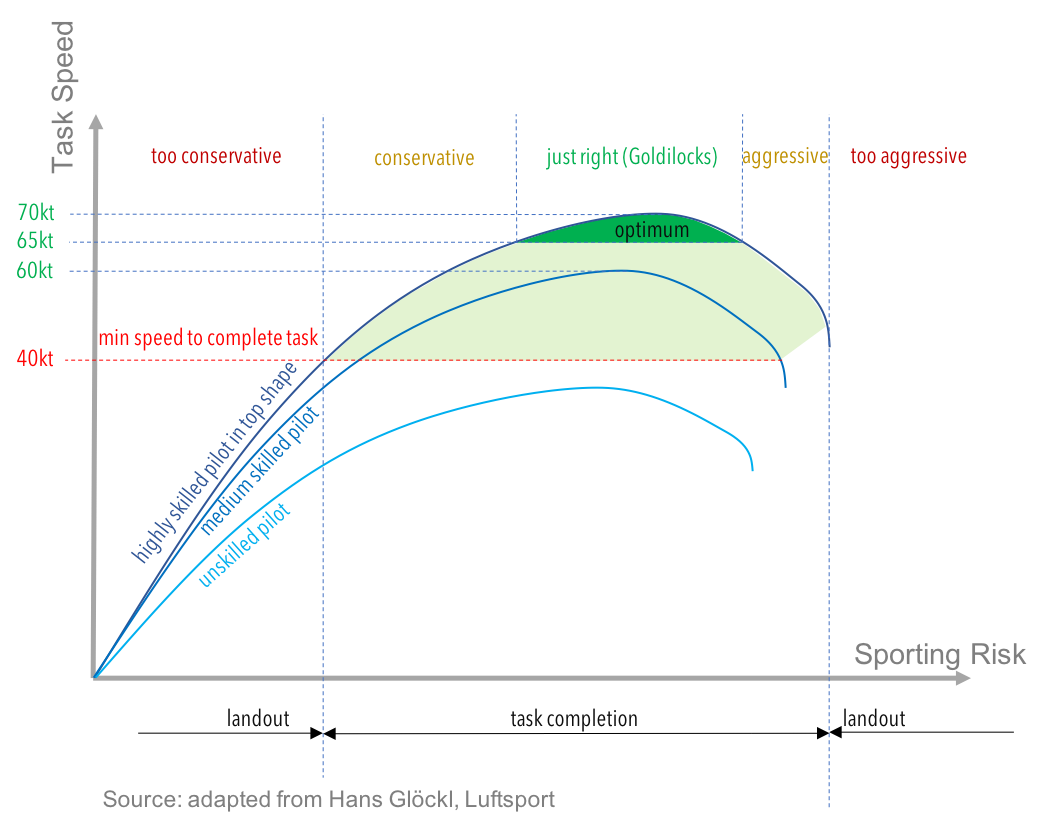

This is also illustrated by the following chart, which shows the attainable task speed on a XC flight as a function of a pilot’s sporting risk and his or her skill level.

Here is how to read this: the chart assumes a task where the maximum attainable task speed for a top pilot is 70kt. You can see that the pilot has to find the optimal sporting risk balance to achieve that speed. If she is more or less aggressive, her speed will remain shy of the 70kt. The chart also assumes that the minimum average speed to complete the task is 40kt. Pilots who are unable to reach 40kt will run out of lift at the end of the day and not be able to finish. Pilots with medium skill can only get to 60kt even if they get their own risk balance perfectly right. (Setting realistic expectations based on one’s skill set is therefore important, and inexperienced contest pilots should not be disappointed with themselves if they can’t get close to the performance of the top pilots even if they perceive that they have done everything right.)

John Bird and Daniel Sazhin have taken the question of how to optimize the Sporting Risks in soaring one step further and proposed that we should adopt one of two different mind frames or “gears” depending on the situation we are in: if the conditions ahead look promising, we should focus on “racing”, i.e. progressing forward on task as directly as prudently possible while flying at MC speeds; if things look bleak, we should shift down and focus primarily on avoiding a land-out while still trying to move forward on task if possible. Their thinking is supported by thousands of computer simulations, which show that this approach is likely to yield a winning strategy. I like the approach also for its practical simplicity: two gears are a lot easier to operate than many. Look up their work as it explains this in a lot more detail.

Risk Management in Soaring is More Complex Than It Is In Other Sports

One aspect that makes soaring different and particularly challenging is the unusually complex interplay of Sporting Risks and Safety Risks. Various sports tend to fall into one of the following categories:

(a) Sporting Risks can be Independent of Safety Risks. In many sports the safety risks are completely unrelated to an athlete’s decision making during a competition. E.g., while tennis players have an elevated risk of getting injured, that risk is not a function of how aggressively they place their shots. When they decide to play, they accept the Safety Risk (which isn’t very high to begin with) as a given and can focus entirely on managing the Sporting Risks. (The same is true for sports where the Safety Risks are negligibly small.)

(b) Sporting Risks and Safety Risks can be Aligned. In many high-risk sports the Safety Risks are a direct function of the Sporting Risk. E.g., a race car driver must manage his Sporting Risk by driving right up to the edge of where the car remains on the track (but not beyond). When his Sporting Risk increases, his Safety Risk increases as well. The two types of risks are perfectly aligned, which means the driver can keep his entire focus on going as fast as possible, just not any faster.

(c) Unfortunately, in some sports, the Sporting Risks and Safety Risks are Misaligned. Soaring falls into this category: in our sport, the relationship between these two types of risks is highly complex. This is problematic because the pilot must constantly manage (i.e. minimize) their Safety Risks, while also trying to manage (i.e. optimize) their Sporting Risks. This challenge can be confusing and at times even overwhelming.

The Complex Relationship of Sporting Risks and Safety Risks in Soaring

The following characteristics make soaring risk management particularly challenging:

(1) Not every Sporting Risk involves a Safety Risk

A pilot who rips through the air at 90-100 kts and skips all but the strongest thermals will certainly take a high Sporting Risk. However, if she always keeps a landable field in safe glide and readily switches from thermaling to landing mode when she’s down at 1000 ft AGL she is not taking a Safety Risk at all.

(2) Life-threatening Safety Risks exist even in the absence of Sporting Risks

A very conservative pilot who flies at MC 0 with a safe arrival altitude of 1,500 ft programmed into his computer might run into a 2-3 minute stretch of 500 fpm sink on final glide, lack the energy to reach the airport, try a low thermal safe two miles shy of the runway, stall and spin in.

It’s critical to notice that the “conservative” MC 0 setting actually contributed to the accident. From a safety standpoint, MC 0 is the riskiest setting to calculate a final glide because it presumes a still airmass and that we are able to fly perfectly at best L/D. A more “sporty” setting of MC 3 or 4 would have been a much safer choice because it would have given the pilot an additional built-in margin. If you’re not sure why that is, I recommend you read John Cochrane’s article “Safer Finishes“.

(3) Sporting Risks can quickly become life-threatening Safety Risks

Consider the following example (from “Perspective: One Contest Pilot’s View…” by Dave Nadler, Soaring Magazine May 1987). “First day of the contest. … I leave the ridge near the turn point, seeing a gaggle. Everyone in the gaggle knows that this thermal will make the difference between a completion and a land-out, on day 1. Pressure’s really on. But the gaggle is not going up. I leave, hoping the others will call it quits and final glide out to the beautiful fields in the central valley, while they can still get past the low obscuring front ridge. I coast down to the turn, click my photo and coast up the valley, picking fields. Pattern altitude, and a nice landing on a lovely golf course fairway. As I taxi off, the panicky radio calls start. Somebody tried to hang on too long in that gaggle, refusing to admit that the day was over until too late. The violent crash was seen from the air. Nobody dares land to offer assistance, the ‘field’ is way too dangerous. Which one of our friends is dead now? Just one day, 3.5 hours of flying, already one dead and two crashes.”

If your mind is focused on the task and making choices to optimize the sporting risks, it can be easy to overlook that a particular choice is no longer just a sporting bet but also a potentially life-threatening safety risk. In the example above, Dave Nadler himself clearly recognized the safety risk in time and switched from Sporting Risk Optimization to Safety Risk Avoidance.

However, it is quite possible that the fateful pilot who tragically lost his life was entirely focused on flying the task and decided to join the gaggle as a sporting move (his priority set to “staying up”) without even noticing that he was too low to “get past the low obscuring front ridge” and “glide out to the beautiful fields in the central valley”. By the time he realized it, he may have already been trapped in an unlandable area. And so he kept trying to dig himself out until it was too late! Up to a certain point in time he could have saved himself by deciding to execute a controlled crash landing in an ill-suited field, or by jumping out with the parachute. But who can really be certain that they would make such a choice under extreme stress and while being entirely focused on trying to climb?

How Can We Manage both Sporting Risks and Safety Risks?

If we consider this complexity and the stress that can arise in the cockpit we can understand why even highly experienced pilots routinely maneuver themselves into situations from where there is no escape.

But understanding alone isn’t enough. We need a recipe, a decision making model, that we can apply in the cockpit to help ensure that we think the right thoughts and do the right things!

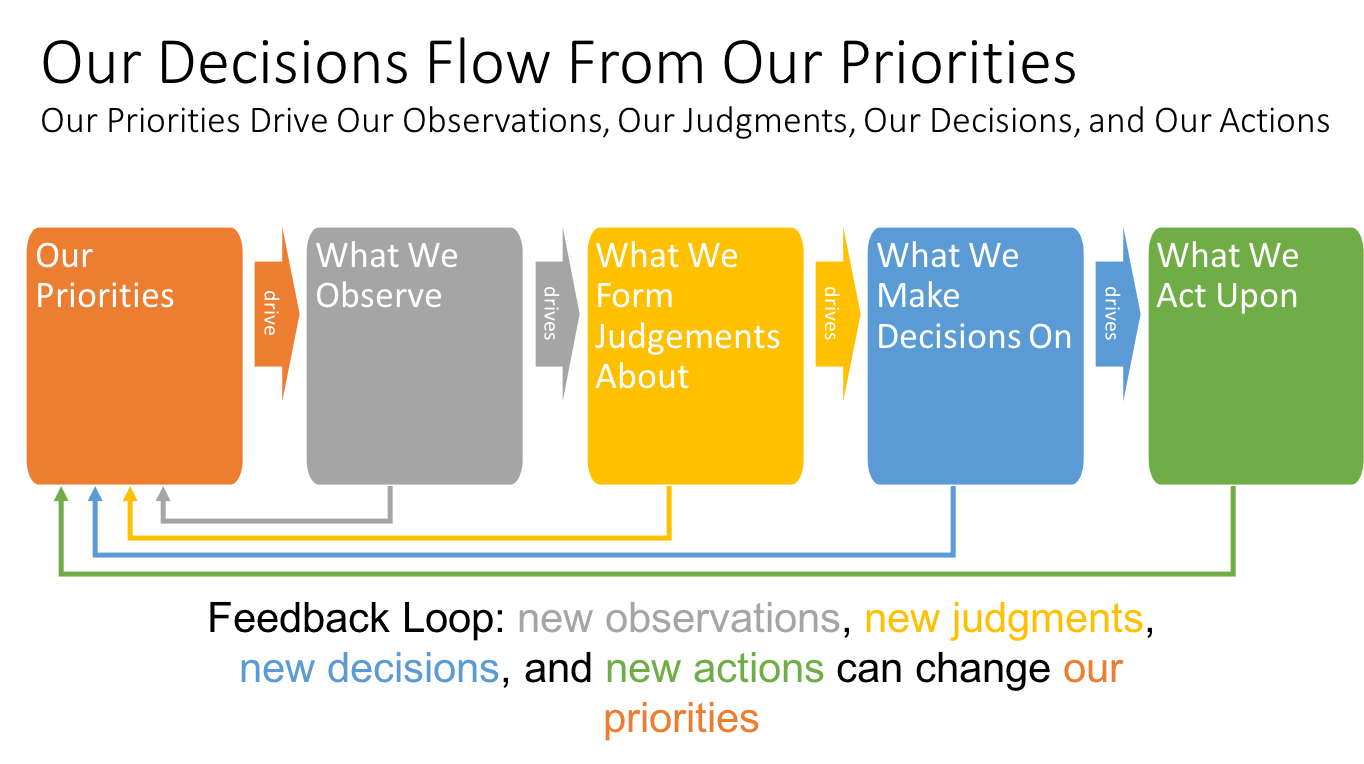

As I began working on this I got good input and feedback from Daniel Sazhin who helped me realize that our observations, our judgements, our decisions, and ultimately our actions are all guided by our priorities. If our priorities are wrong or even just unclear, we might not even see what we need to see; we might not form judgments about the things that need to be judged; we won’t decide the things we need to decide; and our actions will not get us to where we really need to go.

Even if our priorities are right, there is plenty of opportunity for us to make mistakes at each of these subsequent steps (observing, judging, deciding, and acting), but if we have our priorities wrong, we might already be doomed from the start.

The following schematic illustrates how all our decisions and actions flow from our priorities:

Let’s go back to Dave Nadler’s example. If the fateful competitor had his top priority set to “I have to prevent a land-out”, he would have scanned the sky for clues that might help him achieve this objective. When he saw the gaggle, he might have made a snap judgement that there must be a workable thermal allowing him to realize his objective. So he quickly decided to join the other circling gliders. Only after he got there did he realize that the air actually was not going up and that a ridge obstructed his glide out to the land-able fields. (This is of course speculation since we can’t ask the deceased pilot. But it’s easy to see how it could have happened exactly like this.)

What could have prevented this outcome? It’s actually quite simple: he would have needed a different priority! Had his top priority been “I must be safe if things go wrong” he would have scanned the sky and the terrain differently. He surely would have looked for land-able areas and noticed the ridge that ended up blocking his glide to the fields. He would have formed judgments about how high he would need to be when joining the gaggle in order to keep a field in safe glide. As a consequence, his decisions and actions would likely have been very different. (Btw – if you’re certain that you would have noticed the ridge even if your focus was squarely on preventing a land-out, remember this experiment.)

We always say that safety is our number one priority. But this is just an abstract statement unless we make it actionable. How can we do that?

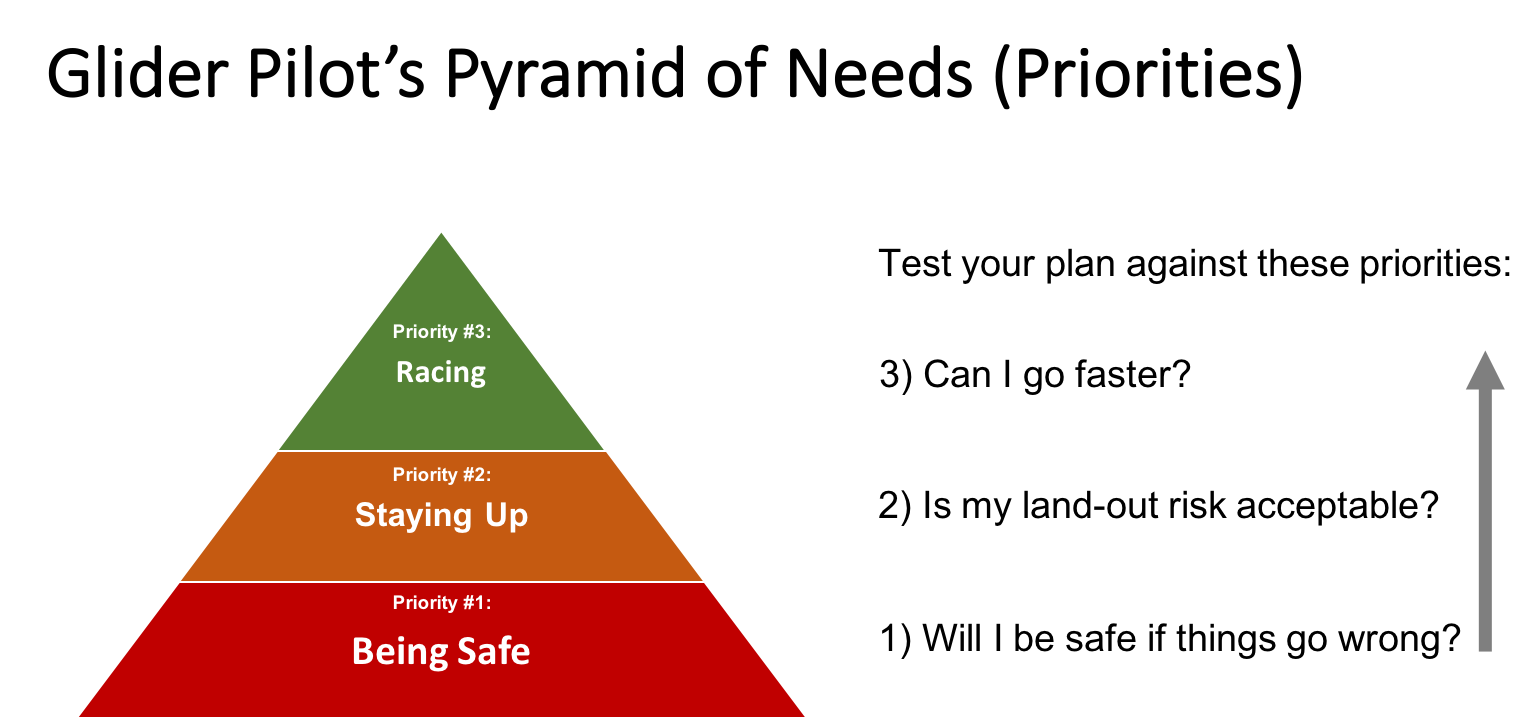

I would like to propose a simple and practical way to do this by stack-ranking our priorities like in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Our first priority, which must guide every single decision, must always be to stay safe. Only if and as long as this need is satisfied can we concentrate on our Sporting Risks. Our second priority is staying up, i.e. preventing a land out. And only if we are high enough that we don’t have to worry about having to land out can we concentrate on racing, i.e. going fast. Our pyramid looks like this:

Aside from being very simple and easy to remember in the cockpit this basic model has a number of key benefits:

(1) It ensures that we think ahead and consider potential Safety Risks whenever we consider a particular plan of action (and not only once we find ourselves in trouble!).

(2) It clearly delineates “Being Safe” and “Staying Up”. These two priorities are easily confused but they are absolutely not the same. Trying to stay up when it is no longer safe to do so is the single most frequent cause of fatal accidents (as I’ve demonstrated before). We must only focus on Staying Up as long as it is safe to do so!

(3) It gives us a blue-print to prioritize our Safety Risks and our Sporting Risks and it is aligned with the “gear-shifting” model as proposed by John Bird and Daniel Sazhin. If the conditions on course ahead are poor we should focus on staying up while continuing to progress forward on course, but only if and as long as it is safe to do so. And if the conditions ahead are strong and we are high enough that we don’t have to worry about staying up, we can concentrate on racing, but also only if and as long as it is safe to do so.

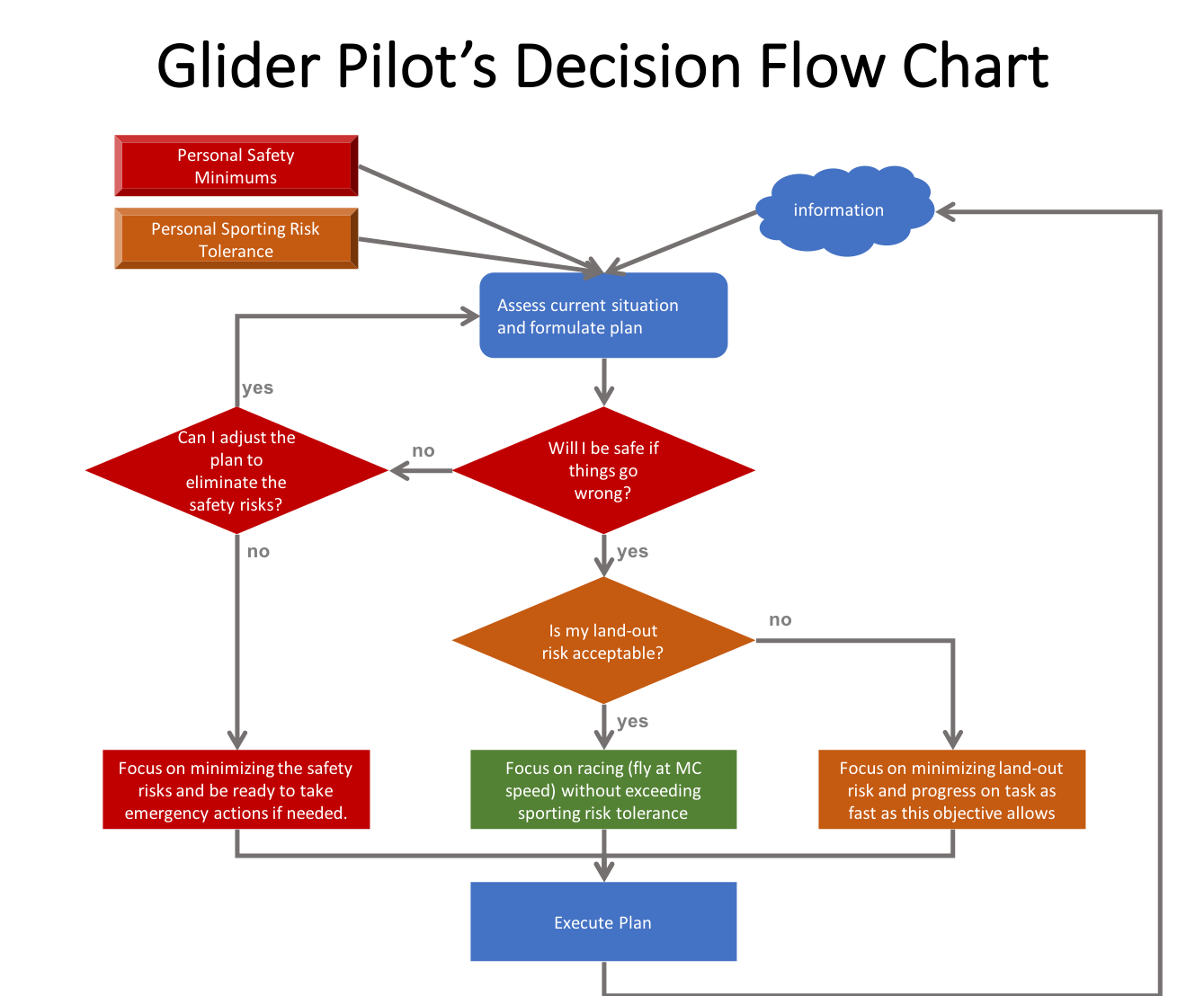

The following flow chart illustrates how we can apply these priorities to formulate, assess, and constantly revise our plan of action as we learn new information. (The colors are aligned with those used in the pyramid chart above.)

When we’re in the cockpit we are repeatedly assessing our situation and are making plans for what to do and where to go. This is shown by the blue box in the upper center. Thereby we must always test our plan of action against our priorities.

(1) We must always test the plan for safety first and ask “Will I be safe if things go wrong?” If the answer is no or even if we’re not sure, we must try to adjust our plan to eliminate the safety risk, or incorporate a contingency plan, i.e., an alternative Plan B or Plan C if Plan A does’t work out as we hope it will. If we can’t think of any way to do either of these things, we are already in a precarious situation: we have no choice but to execute a plan that could endanger our safety. If that is the case, we should also make an emergency plan to safe ourselves in case our only plan does not work out. (E.g.: the pilot in Dave Nadler’s example could have saved himself by bailing out in time or by executing a controlled crash landing. Check with your parachute rigger at what altitude you can still deploy your chute. You might be surprised how low it will work!)

(2) If our plan passes the safety check, we’re ready to test it against your Sporting Risk tolerance. If we’re concerned about having to land out we should be flying in our low gear and focus on staying up while trying to progress on task only as far and as fast as our Sporting Risk tolerance allows.

(3) If we are satisfied that our land-out risk is below our Sporting Risk tolerance threshold, we can focus on racing, i.e. we can fly at McCready speeds and follow the best energy lines.

As we execute the plan, we must watch out for new information that could change our assessment. Our next step will be to test our plan for Safety again so we know we have to look out for information that could impact our safety assessment.

The model is a continuous loop and requires us to cycle through this thought process on an ongoing basis. We tend to get in trouble when we are so wrapped up in execution that we fail to take in new information, especially new information that would change the results of our safety test. E.g., it is possible that the pilot in Dave Nadler’s example joined the gaggle at a time when he was still high enough to glide to safety and that he then got so focused on thermaling in unworkable lift that he did not notice that he had dropped below an altitude at which he was no longer able to cross the ridge and reach a field. Had he reassessed the situation at the time of joining the gaggle and tested his plan for safety he would have surely noticed the ridge and the importance of leaving the gaggle when a safe glide out was still feasible.

We must also remember that we are always testing our plans and not just our current situation! This is an important distinction because it requires us to “stay ahead of our aircraft”. If we do this consistently we can avoid getting into a situation where a dangerous Plan A is our only option.

The practical application of the model works best if you have considered your Personal Safety Minimums and your tolerance of Sporting Risks before you get into the cockpit. This is shown by the two boxes at the upper left of the flow chart.

Your Personal Safety Minimums should be appropriate for your skill level, your experience, your equipment, the terrain you’re flying in, the weather conditions, etc. They might include criteria such as “I will never thermal below x feet AGL”, “I will never fly closer than x wingspans from terrain”, “I will never blindly follow another glider”, “I will always keep a landable field in a glide assuming MC 3 or higher and an arrival altitude of x feet AGL.” Having these minima in place will make it easier to answer the question “Will I be safe if things go wrong?” If you’re confident that you’ll stay within your personal minima you should be pretty safe.

Your Personal Sporting Risk Tolerance is primarily about your willingness to accept a higher or lower land-out risk. E.g. if you are attempting to set a new speed record, you will need to have a high risk tolerance and it may take you several attempts until you succeed (the other times you will land out). If you want to win a multi-day competition with long daily tasks all of which you have to complete, your risk tolerance will have to be much lower. Your experience and skills might play a role as well; however, you should be comfortable with the possibility of a land-out before you go on any cross-country flight. Your Sporting Risk Tolerance helps you answer the question, “Is my land-out risk acceptable?

If you consider the flow chart too complex to use in the cockpit then try to remember at least the simple hierarchy of needs as shown in the pyramid chart. The most important thing is to always ask “Will I be safe if things go wrong?” before you get into a situation where this is no longer the case.

Do We Have To Take Safety Risks To Win A Soaring Contest? In Other Words: Do Reckless Pilots Have a Competitive Advantage?

The history of soaring is full of stories of bravery (or lunacy, depending on your perspective), where soaring pilots “polished the rocks”, “dug themselves out from the height of a barn”, “scraped across the ridge”, or “pulled up over the trees with no energy to spare” to glide to victory.

It is easy to see why pilots may have benefitted competitively by taking such safety risks. Such behavior must have helped pilots prevent land-outs, or cross the finish line minutes earlier than they would have been able to do had they stopped for another climb. They scored higher points and may have even garnered the win on a contest day by flying recklessly.

But does this also mean that pilots who are willing to take such great risks are gaining a competitive advantage in the long run (provided they survive)? If so, we should find that the winningest pilots are also the ones who take the greatest risks.

Last I checked, pilots didn’t wear badges that show how how many life threatening gambles they have already survived. Accident statistics are also not a good source because a single accident is often enough to end a particular contest pilot’s career (or life).

Unfortunately, I don’t think real life provides the data that would allow us to answer this question conclusively. But there is a next best thing to study: Condor. More specifically: the accident rates of pilots participating in the highest level of multi-player Condor racing.

Insights from Condor Racing

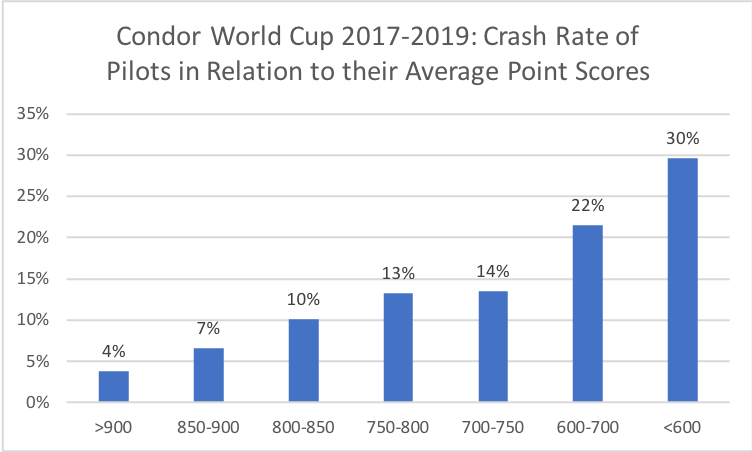

Wanting to find an answer to this nagging question, I analyzed the results of the last three years of a race called “Condor World Cup”. It is hosted by the European Condor Club and has been the most competitive race series over the past three years with almost 300 participating pilots who completed a total of 3,683 race flights. 122 of these pilots finished at least 10 individual races in this particular competition. These are the ones I decided to study. In particular, I wanted to know if those who consistently achieve the highest average point scores are also the ones who have the highest crash rates.

The results are very clear but they show exactly the opposite! Pilots who consistently achieve the best scores actually have the lowest crash rate: pilots who scored more than 900 points on average per race only had a crash rate of 4%; those who scored less than 600 points on average per race had a crash rate of 30%. The following chart shows the crash rate of pilots based on the average point scores that they achieved in the races that they completed successfully.

This is great news for us because it shows that we do not have to take great risks to win a soaring contest! In fact, the opposite is true: those who take the greatest risks tend to end up at the bottom of the score sheet, and those who fly the safest are also the ones who tend to score the highest.

As expected there are some cases where pilots with high crash rates occasionally won a single race. But those cases are a rare exception and these pilots will typically score very poorly on average!

There are of course limitations to using Condor as a proxy for the real world. By far the most important one is the fact that there are actually no Safety Risks in Condor at all. Even crashing is just a Sporting Risk because those who crash will get a zero point score or may be assessed a point penalty. But they can fly again the next day even though in the real world they would have destroyed their plane or even killed themselves. But does this mean the results are not relevant for the real world? I don’t think so: if there were an advantage to be gained from flying recklessly, surely it would be greatest in an environment where the penalty for recklessness is tiny when compared to a real soaring contest. And yet we see that even in an environment that is completely free of Safety Risks, recklessness does not pay off at all!

But WHY Is There No Sporting Advantage To Flying Recklessly?

The data from the Condor study are as clear as they could possibly be, yet they may still feel counterintuitive. What about the pilots who dug themselves out from the weeds or who scraped above the tree-tops to a low energy finish? Why aren’t those the pilots who typically win contests?

I believe the answer can be found in the model that I introduced earlier. Take another look at it, and this time, focus on the green racing box.

The only time when we can focus on racing is (1) when we don’t have to worry about survival, and (2) when we also don’t have to worry about landing out.

In other words: to race we must be flying safe and high enough that we can give our undivided attention to following the best energy lines and maintaining racing speeds. Once we drop down low, we must accept detours and fly at slower speeds. And once we recognize that our safety is at risk, every other consideration goes out the door completely. When we find ourselves in these situations we will most likely not be moving fast towards the finish line!

This does not mean that pilots can never get a benefit from a reckless maneuver. The Condor study does show that pilots with a significant crash history will occasionally win a contest day. But more often than not, reckless flying gets us into situations that will slow us down or even grind us to a halt. To win contests we must avoid these situations!

While we can thus surmise that staying safe is necessary to win contests, it is of course not sufficient. The winningest competitors are those who not only stay safe, but who also manage to find the right balance with respect to their Sporting Risks, and who furthermore have the necessary piloting and racing skills. (The latter are not a subject of this article).

Conclusion

In this article I propose a simple yet holistic model for managing our Safety Risks and our Sporting Risks in soaring contests. One that helps us stay safe and compete.

The model is informed by the basic insight that our observations, judgments, decisions, and actions are framed by our priorities. If our priorities are wrong, chances are that what we see, judge, decide and do will be wrong as well.

Our core priorities in a soaring contest are actually quite simple: in order to go fast we must stay safe first, and stay up second. I call this the hierarchy of soaring priorities: stay safe; stay up; go fast. It means that we can only race when the two more basic/vital needs are satisfied.

To manage these priorities during our flight, we must continuously formulate plans and test them against our priorities, always starting with “stay safe” at the bottom of the pyramid. Our Safety Risk Tolerance should be informed by our Minimum Safety Standards, and our Sporting Risk Tolerance should be specific to our sporting objectives and the length of the task/competition.

We must remember that in soaring, Sporting Risks and Safety Risks are not directly related. Safety Risks exist even in the absence of Sporting Risks, and Sporting Risks can become Safety Risks.

Safety Risks must be avoided (principled approach). A good question to ask ourselves is,”Will I Be Safe if Things Go Wrong?”

Sporting Risks must be balanced (Goldilocks approach). A good question to ask ourselves is, “Is My Land-Out Risk Acceptable?”

Taking Safety Risks can provide a short-term benefit in competition (provided we don’t crash), but it does not convey a competitive advantage in the long run; not even over the course of a multi-day contest. In fact, the opposite is the case: reckless competitors tend to find themselves at the bottom of the score sheet. We must stay safe before we can even focus on staying up. And we must stay up before we can even focus on racing. To be fast, we must maximize the time when we’re racing, and minimize the time when we are looking for lift down low or even trying to survive.

Staying safe is necessary but not sufficient to win races. The winners will be those who fly safe, who appropriately balance their Sporting Risks, and who have excellent piloting and racing skills.

The great news is that we not only CAN stay safe and win. The fact is that we MUST focus on staying safe if we want to have a chance at winning at all!

And that makes me feel better about flying my first contests.

Post Scriptum

I’d like to give special credit to Daniel Sazhin. Daniel kindly critiqued my article “The Risk of Dying Doing What We Love” and encouraged me to think more about how we as glider pilots can reduce our safety risks. When I responded with “Does Soaring Have To Be So Dangerous?“, he once again gave me something to think about when he pointed me to John Boyd’s OODA loop decision model, to which he added the critical insight that our observations, judgments, decisions, and actions flow from our priorities. He also challenged me to explore if our frequent “failure at situational awareness” as discussed in “Does Soaring Have to Be So Dangerous?” isn’t just a consequence of us having the wrong priorities to begin with. This was very instrumental in pushing myself towards developing the integrated risk management model presented here. And this model could not have been coherent without heavily borrowing from the scientific paper “Bounded Rationality and Risk Management in Soaring” which Daniel Sazhin and John Bird published together earlier this year. This work is referenced frequently throughout.

As I mentioned before I do not pertain to have all the answers. But I am convinced that we can make our sport safer by giving more thought to the questions discussed. I welcome further critique and inspiration as it will help me and hopefully others to become better and safer soaring pilots. Have fun and stay safe!

Fascinating and thought provoking.

Your article would make an interesting business metaphor, too. Found myself thinking repeatedly about the parallels

And that led me to consider the problem that humans are not rational, particularly when competing, thanks to, among other things, testosterone.

My Condor results are consistently mediocre despite some (simulated) stupid risk taking. Or maybe, as you suggest, my results are mediocre because of them.

The conundrum is that the more conservatively I fly—an extra turn in a thermal, a slower speed across the flat between ridges—the lower my score. And that encourages me to take (simulated) risks because accumulated seconds lost make the difference. My Maslow-esque risk hierarchy, in the heat of battle, is turned upside down.

(Lest you worry, I hung up my spurs after 50 years in the saddle and the only danger now is to my ego.)

Thanks for the feedback, Tom! I’ve had a long business career myself so maybe it’s not surprising that this comes through 😉 My own Condor results are mediocre, too, but they have actually gotten better after I decided to take lower risks. My own observation is that I will lose a few minutes in a two hour race to the top pilots based just on piloting skills alone (e.g. finding the best energy line along the ridge, thermal selection, speed of centering) and the only thing that will eliminate this difference is practice (the top folks just spend more time in front of their Condor screen). But, usually I also end up making one or two tactical mistakes per race that require some kind of low safe in weak lift and that’s where I often lose another 10-15 minutes. It takes discipline and more forward thinking to avoid those; and that’s a skill that should transfer very well to the real contests…

Best, Clemens

I’ve just finished a contest. On one day the sky was so murky that I gave up and turned back, fearing that I’d meet the Open class head on with little warning (FLARM or visual). The rest of the racing class made the same decision, though some for fear of landing out. One pilot abused the contest director for sending us off into such weather (not always easy to see from the ground).

While I made a sensible decision, I admit that I hung around in a thermal close to the field with a few others, wondering what they were going to do and whether I was making the right choice (only my second contest).

Ultimately I decided that I was the pilot in command and that I had to go with my own judgement – something which seemed to have escaped the abusive pilot.

A good lesson for future contests and future flights.

Gerard – Thanks for sharing this story!