Since gliders have no engine, landing out is always a possibility. Even if you fly locally. A storm can move in, you hit a major unexpected downdraft, or you simply make a mistake on your final glide calculation. And anyone who reads glider accident reports knows that landing out is not the worst thing that can happen. Even gliders with engines do come down in odd places.

So I figured it’s better to be prepared and carry all the stuff that I really need in case of a regular land out or in case of a real emergency situation. Several people have written about it and everyone has their own preferences and risk perception. So what you see below reflects my own choices. I’m always curious to get feedback and input from other pilots and anticipate that my kit will evolve accordingly. For now this is what I take with me on all flights:

Emergency Kit Strapped to My Parachute

In the (hopefully) very unlikely event that I have to bail out of the glider, it’s important to me to carry the most essential things that should allow me to survive a harsh landing in a remote place even if my plane came down on another side of a ridge and I can’t get to any of the stuff that I have stored inside.

I bought a small gadget pouch that can easily and securely be tied to the horizontal strap of the parachute. I attach my Spot Tracker to the outside of the pouch. This ensures that the tracker maintains a satellite connection and sends GPS position data throughout my flight and even when I’m back on the ground. Should I come down with the parachute the tracker will be with me and not in the plane; this should make it much easier for rescuers to find me quickly. Make sure that the batteries in the tracker are good before each flight.

I think of the tracker as the most important item in the kit but unfortunately you cannot fully rely on it. For various reasons it is possible that the tracker does not send regular position signals. This does not occur often but it does happen (e.g. if there is thick cloud cover or you’re in the woods). Also, it is possible that you come down in such a remote area that rescue teams cannot get to you within a reasonable amount of time.

Hence the rest of the pouch: the following contents should help me survive until rescuers can get to me or I can myself get to safety. The pouch is necessarily small, so what I put inside necessarily reflects several tradeoffs:

- An emergency blanket. Cold temperatures are a big concern if you have to camp out in a remote place overnight. I’ll try to add some windproof matches and a tiny saw to the bag as well to be able to start a fire.

- A trauma kit to deal with any potential injuries upon landing with the parachute.

- A zip-lock bag and water purification tablets. Dehydration is a major concern if you come down in the desert and may have to walk for a while. Unfortunately water is very bulky to keep on the body when exiting the plane with the parachute. Hopefully there is a water source somewhere.

- Some minimal emergency food to supply the energy needed to stay overnight or walk several miles if needed.

- A small but loud whistle to catch attention.

- A small headlamp with fresh batteries. If you have to spend the night outside, it may be best to keep moving to prevent hypothermia and dehydration. A light is essential to do that. It also makes it easier to be found in the dark.

- A small credit-card sized emergency tool.

In addition, I wear a runner’s wallet on my right arm containing emergency cash, my emergency information (emergency contact, bloodgroup, allergy information), as well as driver’s license, pilot’s license, and credit card.

Furthermore, I wear my smart phone on my left arm in a runner’s sleeve.

Land-Out Kit in a Hydration Pack

The items above are tied to my parachute or worn directly on my body so they stay with me even if I have to bail out of the plane. In addition, I carry a land-out kit in the glider. For this, I use an old Camelback hydration pack that I purchased many years ago, which holds a three liter water bladder for long flights. The Camelback is also big enough to stuff my entire land-out kit inside. In many gliders I can store it in the luggage compartment behind the headrest and run the hose from the hydration bladder over my shoulder so the water is easily accessible during the flight.

The following items are in my land-out kit:

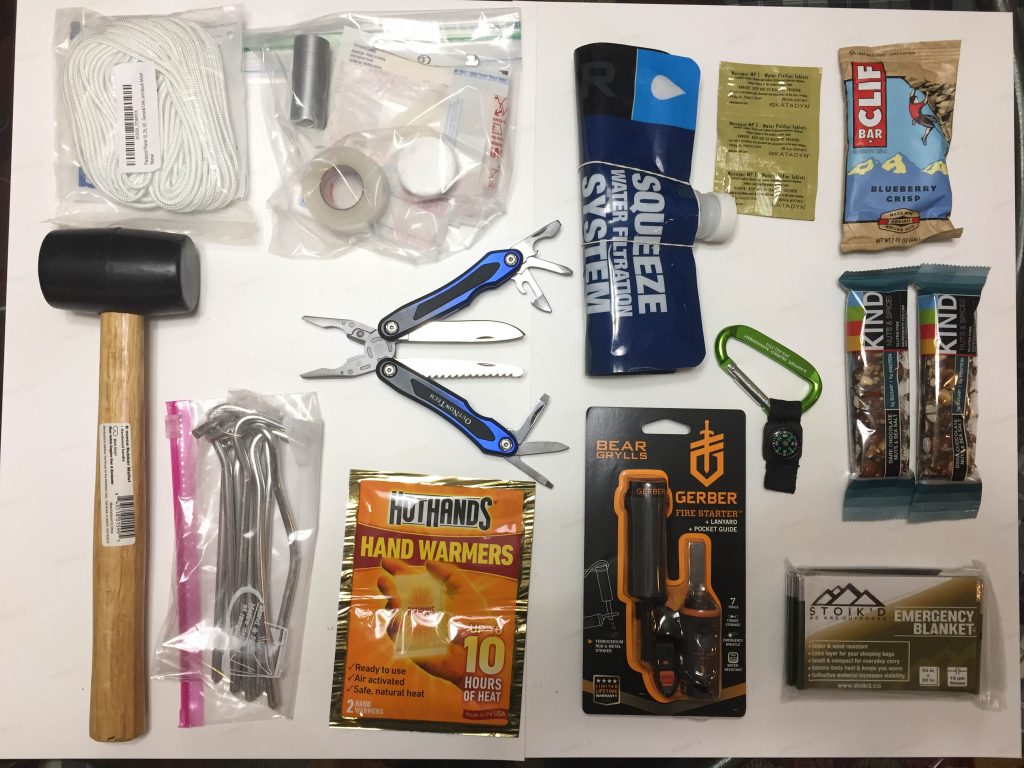

From left to right:

- A tie-down kit comprised of hammer, nylon rope, and tent stakes. This is to secure the glider on the ground following a land-out, e.g. when a thunderstorm is approaching.

- A small medical kit in a zipper bag. My kit contains alcohol wipes, a small assortment of bandages and band-aids, ibuprofen and tylenol (when you’re bleeding you should not use ibuprofen), some tape, and a few safety pins). I also have the trauma kit in my emergency kit (see above).

- A “leatherman-like” multitool.

- Chemical hand warmers.

- An empty 2l water pouch and water purification tablets.

- A fire starter

- A carabiner and basic magnetic compass. (I also have a GPS watch with a built-in compass but it only runs as long as the batteries are good).

- Emergency food.

- An emergency blanket.

Based on the season, I also add some warm clothing and a rain jacket (especially when I am only lightly dressed for flying). I always fly with comfortable shoes that I would be happy to walk in for 10-20 miles if necessary.