Unseasonal warmth greeted me this morning as I stepped out onto our porch to film the clouds in the rising sun. Wearing only shorts and a t-shirt I felt as comfortable as I would on a mild summer’s day. A gentle breeze whisked around the corner as I mounted my camera onto the tripod, pointing it east towards the horizon.

The clouds told a story of winds aloft, but where I stood, in the lower foothills, 400 vertical feet above the valley, and 5,800 feet above sea level, the movement of the air was gentle and kind.

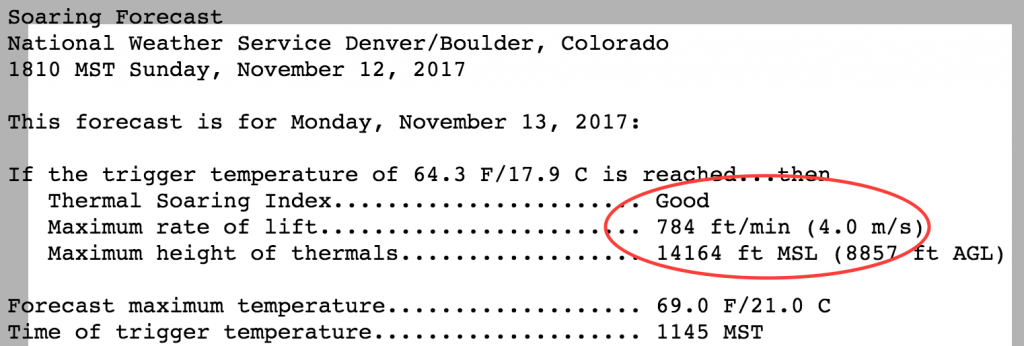

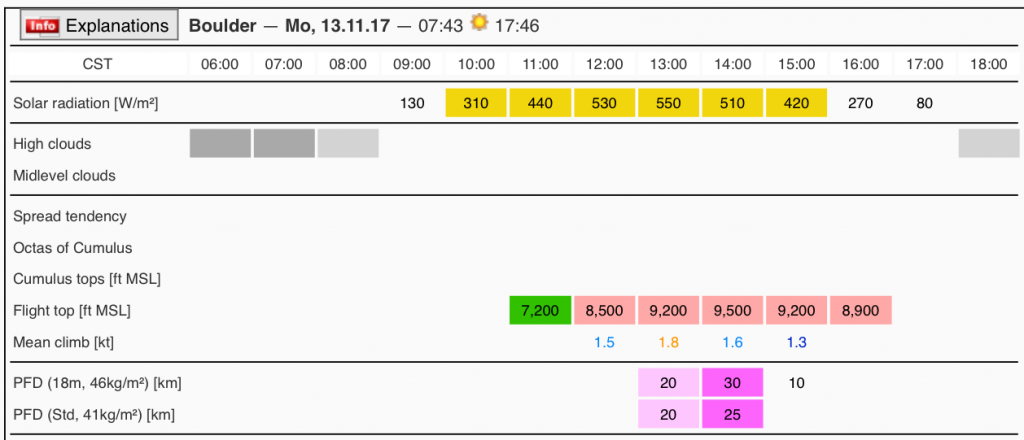

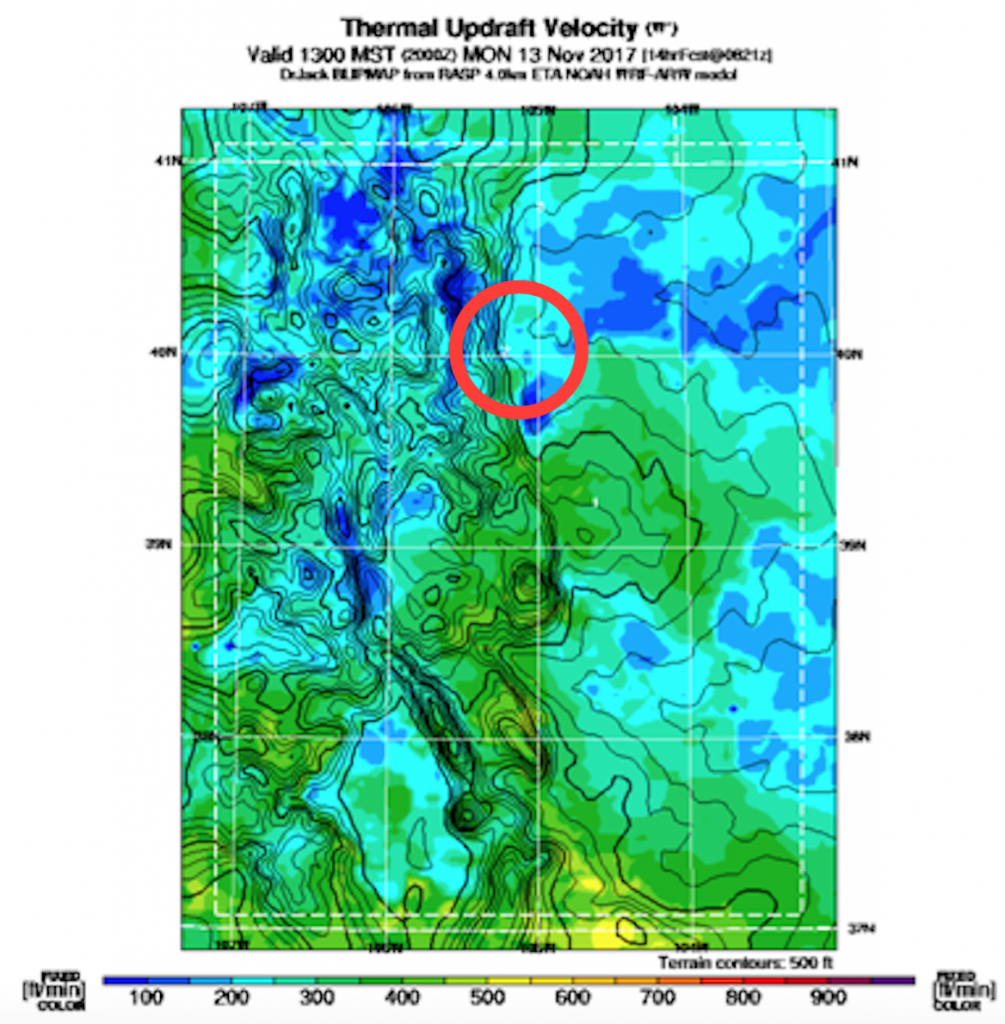

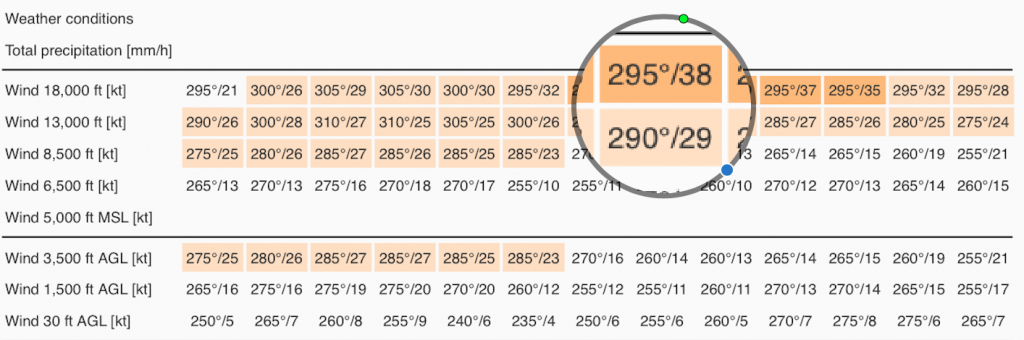

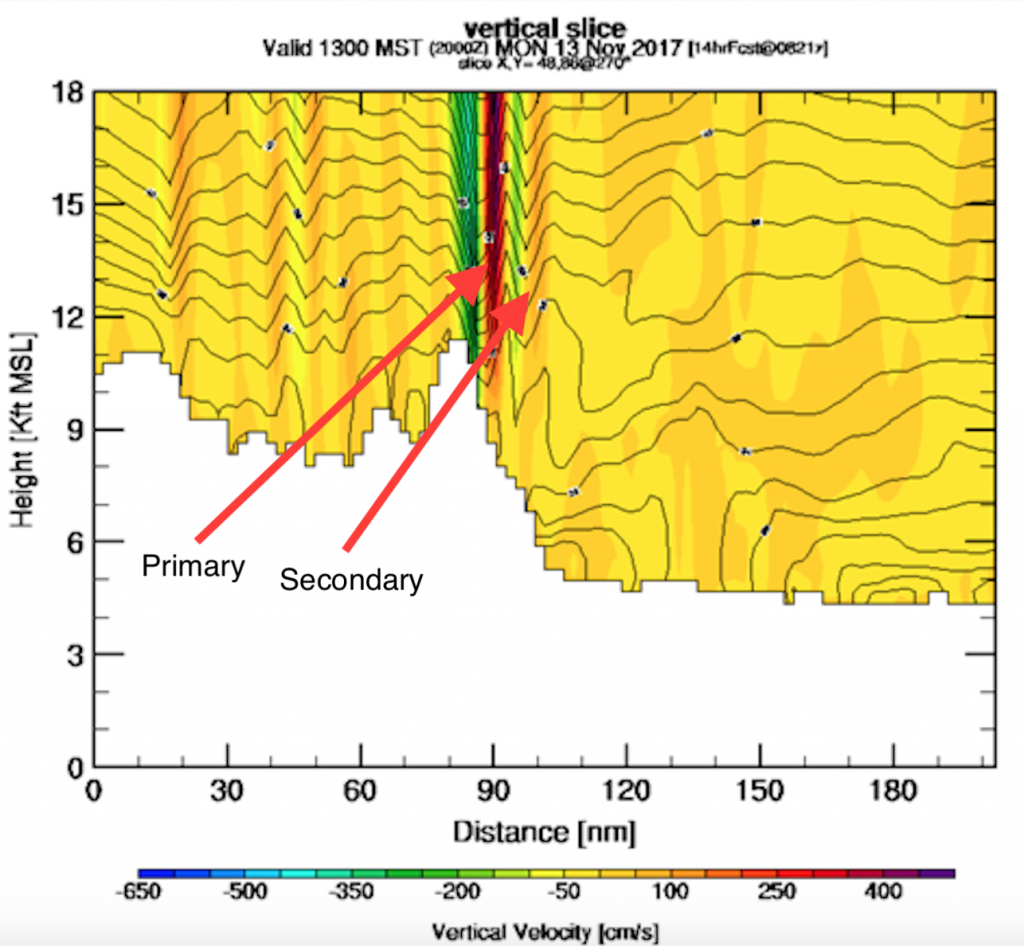

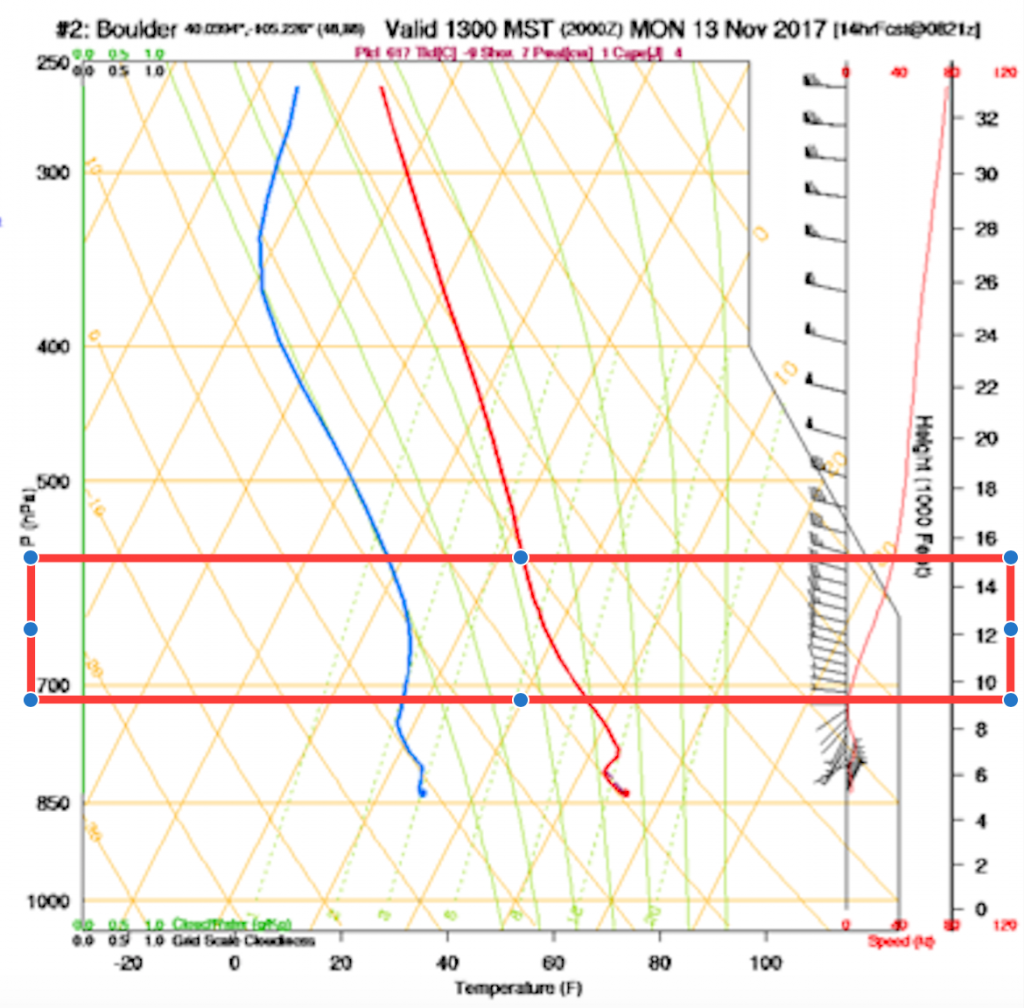

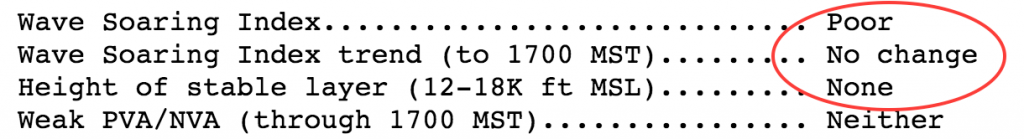

The night before, the outlook had already looked promising for my first soaring flight in the New Year: TopMeteo projected westerly winds of 30 kts at 12,000 feet, increasing to 40 kts at 18,000 feet. Meteoblue projected a stable layer between 11,000 and 15,000 feet – right around the tops of the mountains. Dr. Jack’s cross-section chart for Boulder indicated multiple wave bars with modest climb rates even though it projected the wind to have a pronounced southerly component. Based on past experience, I decided to – once again – dismiss the Soaring Forecast from the National Weather Service, which predicted good thermals (very unlikely in the flat January sun despite the unusually high temperatures) and poor wave conditions.

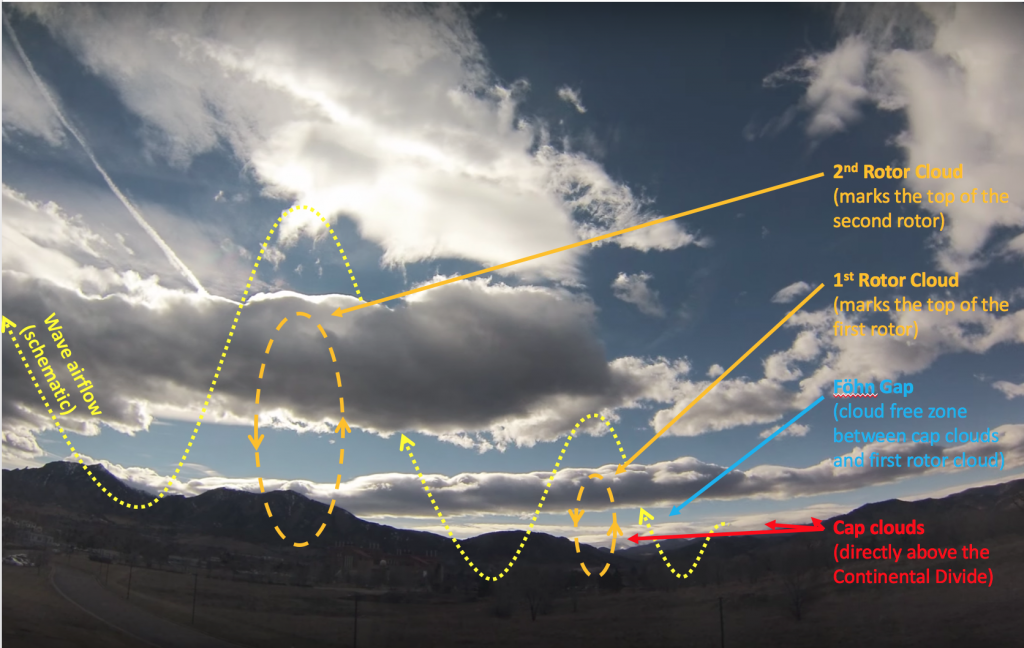

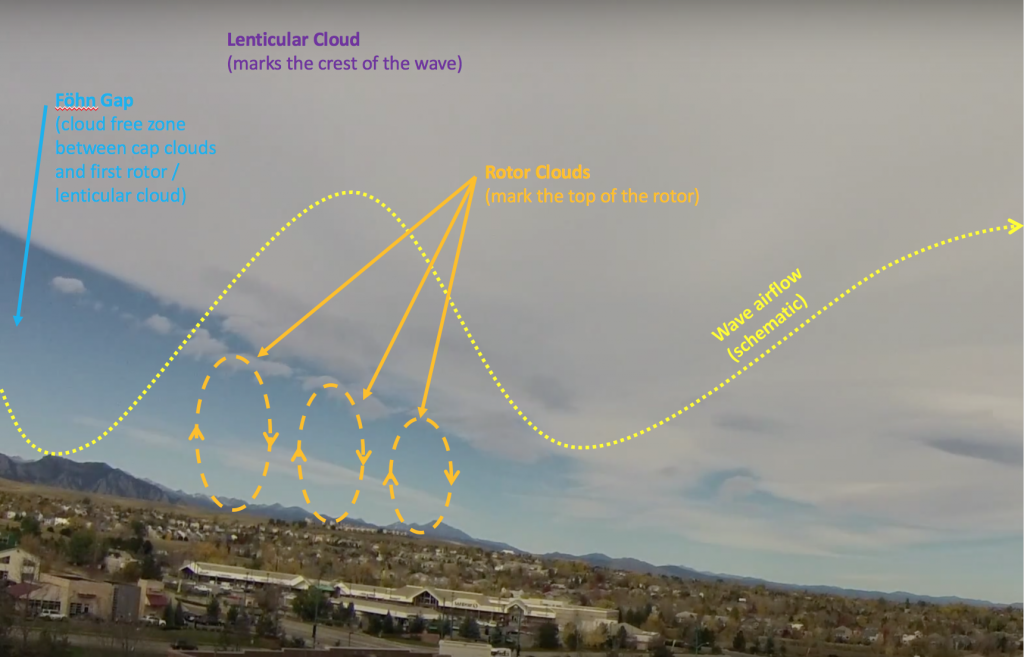

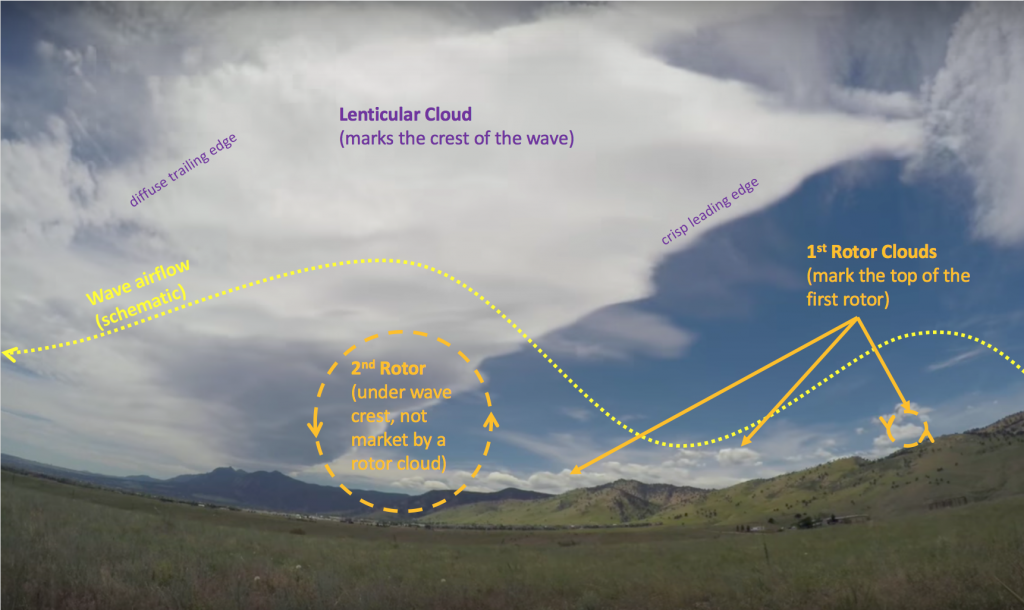

But the best indicator for good soaring conditions was right in front of me: beautifully turning rotor clouds – as always an unmistakable indicator of mountain wave.

On my way to the airport I reflected upon my most recent wave flight, which was characterized by extreme turbulence below 13,000 feet. I braced myself for the possibility of earning another set of bruised shins even though I was hopeful that the comparatively modest wind speed might be a mitigating factor.

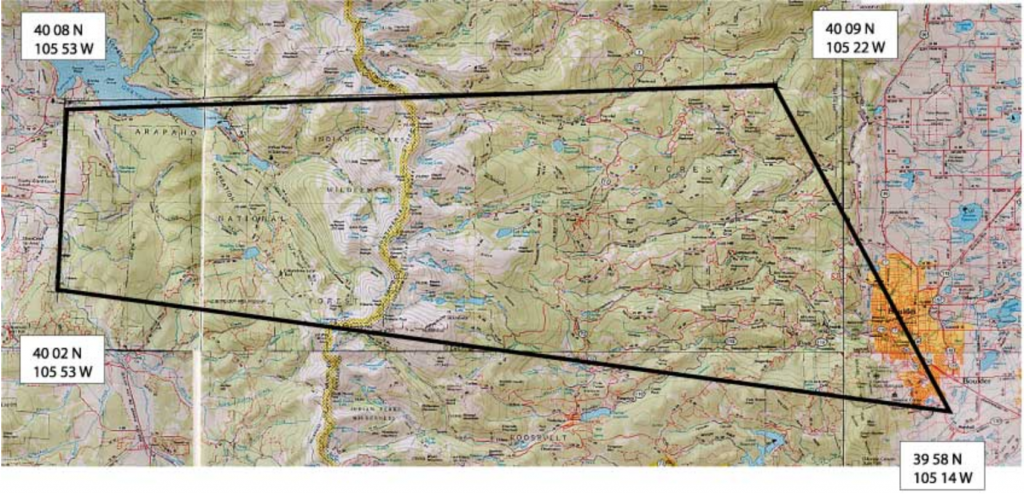

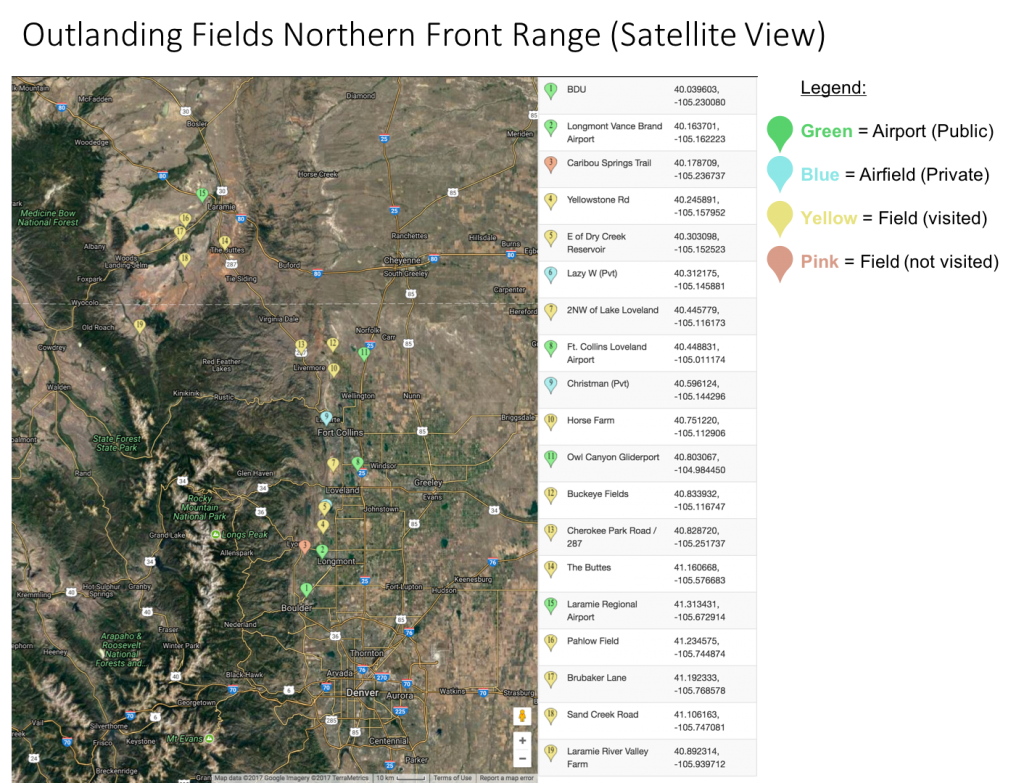

One decision was made for me already: I had learned at my club’s monthly meeting that a recent attempt to open the Arapahoe Wave Soaring Area (which allows flights above 18,000 feet within a pre-defined area) had failed because Air Traffic Control was completely unaware of its existence. This would be clarified in an upcoming meeting with ATC but until then it would be better not to put in further requests. This meant that I would have to stay below 18,000 feet and not have a chance to earn Diamond Altitude (which requires a 5,000 meter (16,400 feet) altitude gain in soaring flight after release from tow). It also meant that I would not need to bring the more sophisticated oxygen equipment required for flights further aloft; and there was one more benefit: the risk of freezing my toes off would be much reduced 😉

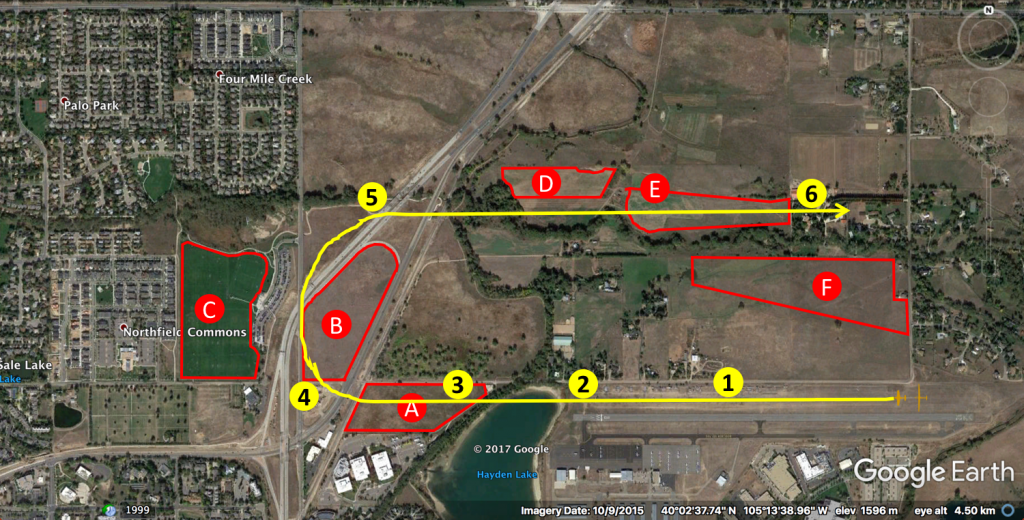

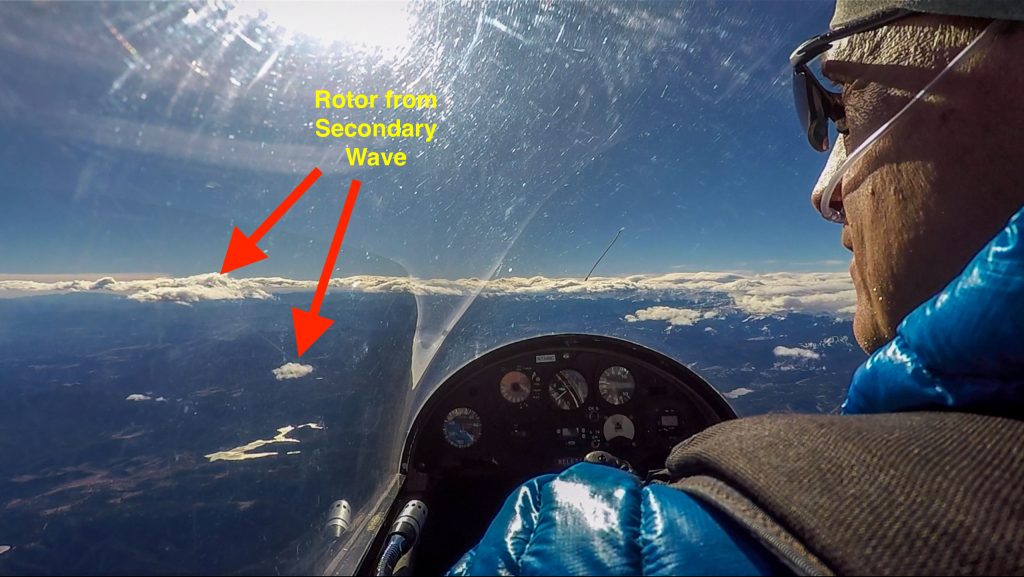

At 11:00am local time I was the first pilot of our club ready to launch. There were two beautiful lines of rotor clouds in the sky, indicating the positions of the primary and the secondary wave. There were also some isolated rotor clouds from the tertiary just to the north of the airfield. I asked the tow pilot to take me to the upwind side of the secondary, which seemed to promise the opportunity for a longer flight along the wave bar.

After two initial turns near the airfield to gain altitude I followed the towplane toward the northwest. Soon after we had passed underneath a small rotor cloud from the tertiary we encountered the first pockets of strong lift.

When the third pocket of lift had lasted more than a few seconds I felt comfortable to release from the tow. I would try to climb in the tertiary and then attempt to push forward into the secondary without the help of a tow plane.

After releasing my first focus was to stay in the area of lift to reach a more comfortable altitude. (2,600 ft AGL may sound unproblematic but where there is strong lift there is also strong sink, and 2,600 feet may only equate to two minutes of remaining flying time if I were to encounter a major downdraft.)

I looked at my GPS (mounted to my right and not visible in the pictures) and quickly worked out the the crab angle necessary not to drift further away from the mountains. The wind speed was considerably weaker than during my previous wave flight. There was some turbulence but nowhere near as pronounced as during my prior wave flights in Colorado.

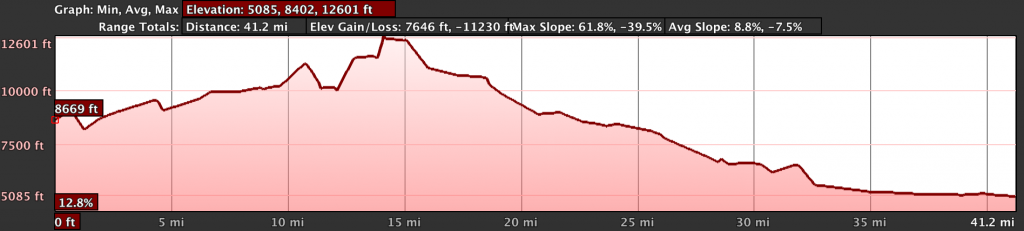

The area of lift in the tertiary was not very large. However, it was surprisingly calm even though I never reached a truly laminar air flow. The lift was moderately strong, varying from 5 to 10kts. Within 20 minutes after takeoff I climbed through 17,000 feet.

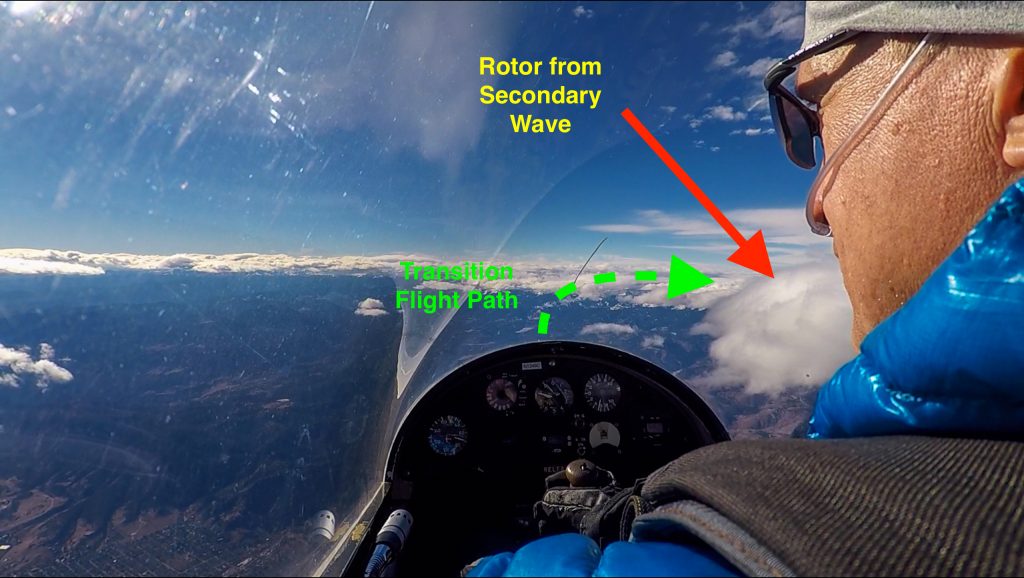

After some time in the tertiary I decided to try to move forward into the secondary. I looked for a gap in the clouds along the secondary rotor line and pushed forward into the wind. Vividly remembering my prior wave flight where I lost more than 6,000 feet during a wave bar transition I prepared for the potential of a similar loss in altitude.

This time however, the transition turned out to be easy and smooth. There was some modest sink along the way but the entire push into the wind did not take more than three minutes during which I only lost 1,500 feet.

Having arrived in the secondary, the lift was clearly stronger, and within two minutes I was back at just under 18,000 feet. Although the line of clouds was interspersed with blue skies it was fairly easy to locate the area of lift. I increased the airspeed of the Schweitzer 1-34 to 80mph and flew south where I could see the next clouds to the west of the Flatirons. I looked at the shape of the Continental Divide to my right and sought to maintain a more or less constant distance to the mountains, accounting for the direction of the wind, blowing from WSW.

West of the city of Golden I turned around and retraced my route to the north, again following the line of lift. Without a single turn I continued to fly straight for over 40 miles until I was just west of Carter Reservoir. The lift in this area (north of Lyons) was the strongest of my entire flight: I had to fly at 90 mph with the air brakes fully extended in order to neutralize the lift and keep the plane below 18,000 feet. Next to me was an imposing rotor/lenticular cloud, its western side almost vertical, extending many thousand feet above and below my flight level. Based on my location and the direction of the wind, I assumed that the airflow forming this massive cloud was likely triggered by the steep downslopes of Mount Meeker and Longs Peak. (I noticed that this area lies outside the boundaries of the Arapahoe Wave Soaring Area so I could not have used this location to climb above 18,000 feet even if the wave window had been active.)

From there I flew back towards the south. I briefly contemplated a push forward into the primary but at this point my feet had become quite cold and I decided to call it a day and return to the airport.

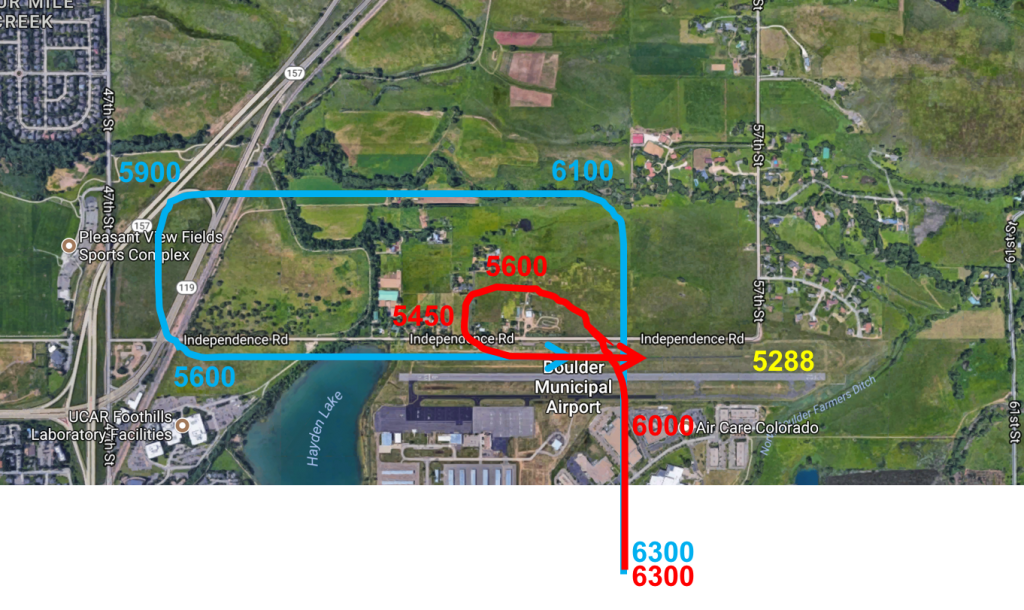

The frozen lakes surrounding the Boulder airport reminded me that it was the middle of winter. Obviously, they were of no help detecting the wind direction on the ground. However, the windsock, once in sight, was easy to read, showing a stiff breeze straight from the west.

I entered the landing pattern at 1,500 feet AGL and turned onto final at the end of the runway, still almost 1,000 feet above ground. I pushed into the wind, flying the final approach at an airspeed of 80mph. Seconds later, I touched down gently at a very low ground speed, just fast enough to roll the remaining 100 feet right up to the parking position.

Here is a link to the flight track.

For those interested, I have also compiled a lot of information about wave flying that you can find here.

Lessons Learned

- A high tow may not be necessary to reach wave lift. I released at 7,900 feet and had no problem at all to climb into the tertiary. Today, the first good climb on tow was at 7,300 feet. It would have probably been sufficient. To practice, I need to be willing to release early and risk having to take a second tow. This is especially important with respect to reaching Diamond altitude. With today’s release altitude I would have had to climb to 24,400 feet to accomplish a gain of 5,000m (16,404 feet). If I could release even earlier, I would not have to fly all that high.

- Rotor turbulence can be gentle. Today’s rotors were very different from those I encountered during my most recent wave flight. I attribute today’s conditions to the much lower wind speed at altitude (about 25 kts versus 50 kts). On Nov 16 the winds were so strong that I struggled to make progress along the wave bar because most of my air speed was needed to push into the wind, whereas today the necessary crab angles were fairly modest. The flight on Nov 16 offered a bigger challenge. Today’s offered more pleasure.

- Laminar air flow may only start above 18,000 feet. During today’s flight I never encountered a fully laminar air flow. That tells me that the rotors extended well above 18,000 feet. There was only little moisture at altitude; however, I did see a few lenticular clouds high above the rotors (my guess is above 30,000 feet). Today would have likely been a great day to reach Diamond altitude.

- Good climb rates are possible even when wind speeds are moderate. It does not take a howler to produce good climb rates in wave conditions. Today’s climb rates were between 5-10kts in the tertiary and reached well above 10kts in the secondary. At one point the average netto climb rate was 14kts at an altitude of just under 18,000 feet (demonstrating the great potential of today’s lift.)

- Wave transitions don’t have to cost a fortune (in altitude). Rotor clouds can be super helpful in identifying the best locations for a (forward) transition from one wave bar to another. Today I deliberately picked a spot “in the blue” to push forward into the wind. This did not only reduce the risk of getting sucked into a cloud, it also dramatically reduced the sink rates encountered and therefore the amount of altitude lost during the transition.

- New rotor clouds develop within seconds. While I experienced no close encounters with developing clouds I observed numerous times how new clouds can form within seconds. It is critical to always be aware of your location relative to the line where new clouds could possibly form. Especially when a strong crab angle is required it may be difficult to spot that you are about to be engulfed in (newly developing) clouds from behind.