My last post titled “The Risk of Dying Doing What We Love” presented the results of a statistical analysis where I compared the risk of flying sailplanes to other things we love to do such as cycling, horse back riding, paragliding, etc.

I showed that the risk of dying in a soaring accident is approx. 1 per 50,000 flight hours, which makes soaring per activity hour about 2x as dangerous as riding a motorcycle, 25x as dangerous as cycling, 40x as dangerous as driving a car, and almost 200x as dangerous as traveling on a commercial airline flight.

The post struck a core. Within just a few days, it was read tens of thousands of times and many of you have shared your thoughts and asked really important questions. Perhaps the most important ones were:

Does soaring have to be so dangerous?

How can each of us make it safer for ourselves?

To answer these question I read, interpreted, and analyzed about 250 glider accident reports. My main sources were Germany’s Bundesstelle für Flugunfalluntersuchung (154 reports since 1998) and the United States’ National Transportation and Safety Board (93 reports for the past five years). I chose the US because that’s where I do most of my soaring and also because it’s a very large country with varied soaring conditions including flatland, ridge, mountain, desert, and wave soaring. Germany was a logical choice because it accounts for about one third of all soaring activities worldwide, and also because the quality of its accident reports is particularly high. In addition, I also reviewed the equally detailed soaring accident reports for Austria since 2010 (25 reports) and read the 2019 EASA Safety Report.

Classifications in the EASA Safety Report

The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) provides a statistical analysis of aviation accidents between 2008-17 in its 2019 Annual Safety Report (gliders are covered starting on page 108) that classifies glider accidents as follows:

a) By phase of flight. 21% of European soaring accidents happened during takeoff, 50% during landing, 12% on the landing approach, and only 17% en route.

b) By type of operation. 6% of accidents occur during competition, 22% during flight training, and 72% during pleasure flights.

c) By Safety Risk. The EASA report breaks fatal accidents between 2014 and 2018 down by what happened: 26% of accidents were the result of a “Stall/Spin”, 17% were a “Collision with Hill”, 10% were due to an “Incomplete Winch Launch”, 8% were due to “Loss of Control”, another 8% happened in “Other Flying”, 7% were “Mid-Airs”, 7% “Technical”, 5% “Misuse of Controls”, 4% “Aerotow”, 4% “Medical”, and 4% “Other”.

Each of these classifications conveys some useful information. E.g., we need to be particularly careful during takeoff and landing. Most accidents occur during normal pleasure flights. Flight training needs to ensure that student pilots learn to fly coordinated and at the appropriate speed. We have to be particularly careful near hills and mountains, etc.

However, none of these classifications actually tell us why accidents really happened. What was it that caused the pilot to fly so slowly that she stalled and spun in? What made him collide with the hill? What caused her winch launch to be incomplete? Could he or she have avoided these outcomes? How? To answer these questions, we have to dig one or two layers deeper and get to the root causes.

(Btw – the soaring accident reports of the National Transportation Safety Board in the US frequently mention “Loss of Lift” as the defining event of accidents. Don’t we experience loss of lift all the time when we go soaring? This really should not be viewed as a reason for an accident!)

What causes soaring accidents really?

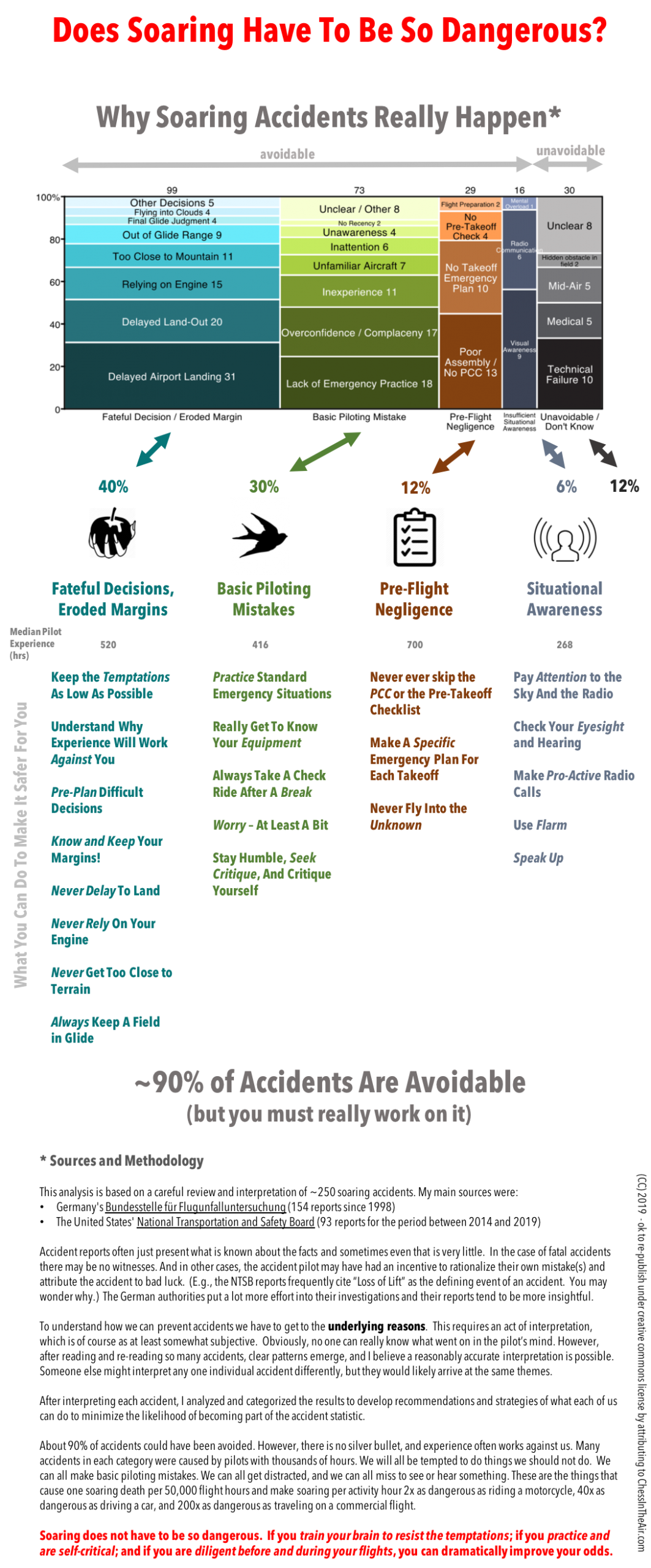

My analysis shows that approx. 90% of soaring accidents were caused by pilot mistakes. (10% were not and we will get to those also.) Four fundamentally different types of pilot mistakes accounted for the vast majority of accidents:

a) Accidents where – through improper decision making – the pilot had maneuvered him- or herself into a situation where proper handling of the aircraft was either impossible and/or no longer sufficient to avert a bad outcome. That’s why I’m calling them “Fateful Decisions.” In most instances the pilot didn’t even actively decide to take on a great risk, he or she simply failed to make a decision that could have prevented the accident. In other words, he or she allowed the safety margins to erode until it was too late. Examples include delaying the decision to land (at an airport or in a field); relying on an engine, flying too close to mountainous terrain; failing to stay within gliding distance to a save landing area; failing to interrupt a final glide when the altitude was not sufficient to reach the airport; failing to descend from a wave flight before the cloud layer closes; etc.

b) Accidents that were caused by improper handling of the aircraft and could have been avoided in the moment by good Basic Piloting Technique alone. E.g., failing to maintain sufficient airspeed during a winch launch; flying uncoordinated through a turn; cycling the gear instead of extending the airbrakes; not knowing how to stop a spin at altitude; getting out of position behind the towplane; etc.

c) Accidents where the pilot’s Pre-Flight Negligence resulted in a situation where good piloting technique alone was of no help to prevent a bad outcome. E.g., assembly mistakes such as failure to connect the controls and/or conduct a Positive Control Check (PCC); failure to go through the pre-flight checklist; failure to communicate the presence of water ballast to the tow pilot, etc. A very important special case of pre-flight negligence is the failure to have a specific pre-takeoff emergency plan. Many premature release accidents were caused by the pilot waisting precious time and altitude before deciding what to do and where to land.

d) Accidents that were caused by Insufficient Situational Awareness of the people involved. Most but not all of these were mid-air collisions that could have been avoided. Insufficient situational awareness might mean inadequate radio communications, insufficient look-out, or simply the failure to observe warnings that are there in plain sight.

If you look at past accidents through this particular lens, the following picture emerges:

Approx. 88% of accidents can be explained by the three types of pilot mistakes outlined above.

Fateful Decisions / Eroded Margins account for ~40% of accidents and are the single biggest factor.

Basic Piloting Mistakes accounts for ~30% of accidents.

Pre-Flight Negligence is the main cause of ~12% of all soaring accidents.

Insufficient Situational Awareness accounts for ~6% of soaring accidents, most of them mid-air collisions.

The remaining 12% of accidents are either unclear (e.g. the cause of the accident could not be identified) or they were truly unavoidable.

The following chart summarizes my findings. A more detailed analysis and discussion follows below.

Let’s examine each of these types of accidents in more detail and discuss what we can do to avoid them.

1) “Fateful Decisions / Eroded Margins” or: the Failure to Resist Temptations

Soaring requires constant decision making and decisions have consequences. It is not surprising that the largest group of accidents (40% overall for the data I looked at, in the US the share is even greater at 44%) are the unavoidable consequence of a decision that the pilot had previously made or failed to make during the flight. In other words: by making a wrong decision they had gotten themselves into a situation where good piloting technique alone was not enough prevent a bad outcome.

There is logically no limit to the kinds of decisions that could get us into trouble. However, a close look at accident reports reveals that most of these “fateful decision accidents” can be traced back to just a few types of mistakes. Let’s look at each of these in more detail, approx. in the order of frequency in which they occurred, starting with the most common ones first.

Delayed Airport Landing – Failure to make a timely decision to land and stick to it

It may seem surprising but many fateful decision accidents happen right next to the home airfield when the pilot is trying to extend their flight beyond the time when they should have made the decision to land. Here are some examples:

- An experienced airline transport pilot had returned to the airport at the safe altitude of 800-1000ft AGL but kept circling next to the airfield down to 300ft AGL, still looking for lift. When he finally extended the gear, the glider stalled and spun in. Like many of these accidents, the outcome was fatal.

- Pilot thermalled next to the airport at 400ft AGL, the glider stalled and spun in.

- An airline transport pilot had already entered the landing pattern when he decided to circle again at 300ft AGL. The glider stalled and spun in.

- Pilot circled above airport at low altitude, stalled and spun in.

- Pilot with 1900 hours of experience entered landing pattern at a very low altitude, stalled and spun in.

- Pilot with an experience of 2148 flights stalled and spun in at 15ft AGL on the turn to final.

- Pilot delayed pattern entry to wait for another glider to clear the runway, ran out of altitude and came short on final.

- Pilot with 550 hours of experience delayed pattern entry due to strong winds, got too low and collided with tree on downwind leg.

- During check ride to earn a CFIG, pilot and instructor with 2700 hours of experience entered pattern too low and collided with a tree during last-second attempt to divert to a field.

- Student pilot entered pattern too low, stalled, and spun in.

- Pilot unnecessarily delayed pattern entry, stalled and spun in on turn to final

- Pilot stalled and spun in while thermalling at 600ft next to airport. Managed to exit spin close to the ground, pulled up to avoid tree, stalled again, and crashed.

- Pilot entered pattern too low and flew final approach close to the ground, stalled and spun in.

There are many more accidents that follow this same pattern. About two thirds end with a “stall and spin” and most of the other ones end with the glider colliding with a tree, power line, or another obstacle.

To avoid “stalls and spins”, student pilots are usually taught to fly coordinated and at a proper airspeed. This is of course good advice but it is not sufficient. These accidents were typically not caused by pilots who did not know that they had to fly faster and coordinated. The problem was that they had already maneuvered themselves into a situation where they were no longer able do that. E.g., a pilot who finds themselves within feet of the tree tops on their turn to final is already in an impossible situation. They could either keep the speed up and crash into a tree or they could attempt to get over the trees by pulling the nose up and using the rudder to keep the wings level. They will of course try the latter but it is also the best recipe for a stall and spin.

These accidents continue to happen even though they should be quite easy to avoid. All the pilot has to do is to enter the landing pattern at a safe altitude where the temptation to fly too slowly and/or too uncoordinated doesn’t occur to begin with, and where they have enough altitude/energy reserves to deal with unexpected sink or headwind on final.

What is a safe pattern entry altitude? In my experience there is no standard rule of thumb that fits all situations. In normal soaring weather and light winds a pattern entry at 800 ft AGL will be adequate most of the time. However, I have personally experienced that even 1000ft can be too low for comfort. And under extreme circumstances, you may want to be even much higher than that.

Delayed Land-Out – Failure to make a timely decision to land-out and stick to it

All of the accidents mentioned above happened right next to an airport. Similar accidents also occur frequently during XC flights when the pilot delays a decision to land in a field.

In some ways, these accidents are just special cases of failing to make a timely decision to land. All of the considerations above – especially the need to make the decision at an appropriate pattern entry altitude – apply here is well.

However, land-outs must be given special attention because the decision to land in a field is much more difficult to make than the decision to enter the landing pattern at the home airfield. Landing out is inconvenient. Selecting a field is stressful. There is a higher risk that the glider gets damaged. The prospect of having to deal with the land owner may be off-putting. The pilot may feel embarrassed that they did not make it back home. In gliding contests, there is an even greater impetus to stay aloft. In short, most pilots view the prospect of a land-out as a big negative. To avoid it they are tempted to keep searching for lift well beyond the time when they should have made a decision to land.

Daniel Sazhin, a PhD student of cognitive psychology, and one of the best contest pilots in the United States, explained in this excellent article that this is exactly the kind of situation in which pilots are likely to gamble and take the greatest risks.

The only reason that these accidents aren’t even more frequent is the fact that only the minority of pilots ventures beyond gliding distance of their home airport.

- Very experienced pilot failed to make timely landout decision, got too low, flew too slowly to avoid hitting terrain, stalled and spun in.

- Pilot with 200 hours of experience thermalled at a very low altitude, stalled, and spun in.

- Pilot with 1800 hours of experience flying close to the home airport and over landable terrain, failed to make a timely land-out decision, circled at a very low altitude, stalled and spun in.

- Pilot circled at 300ft AGL in the vicinity of an airport, then crashed into power lines, likely while attempting an off-field landing.

- Pilot with 1300 hours of experience circled until very close to the ground, then impacted terrain on final turn to runway.

- Pilot with 1100 hours of experience circled at 400ft AGL, stalled and spun in. Pilot did not attempt to use sustainer engine.

- Pilot with 260 hours of experience made land-out decision too late, selected a short, down-sloping field, approached with a tailwind, tried to correct, and crashed.

- Pilot with 1500 hours of experience thermalled at 450 ft in turbulent conditions, stalled, and spun in.

- Pilot with 1600 hours of experience thermalled at 500ft, decided too late on a landout field, and collided with a building while attempting to reach the field.

- Pilot decided too late to land out despite well-suited terrain. He got so low that he impacted the ground on the turn to final.

- Pilot circled 300ft above ground. Decided to land and noticed a power line on the approach to land-out field, diverted to another field at last second (without having being able to examine it) and hit a bump in the field.

If you decide to fly cross-country, anticipate – in John Cochrane’s words, that “you will be tempted”. I.e., the only way to avoid these accidents is to resist the temptation(s). But how do we do that? I’ll get back to this question at the end of this chapter on fateful decisions.

Out of Glide Range – Failure to stay within glide range of an airport or a landable field

Making a timely decision to land obviously pre-supposes that the pilot stayed within glide-range of an airport or a landable field to begin with. Doing so is one of the most fundamental lessons all glider pilots are taught.

- Pilot with 2100 hours of experience continued his XC flight in deteriorating weather conditions over unlandable terrain; was forced to land on a road, one wing impacted terrain; glider cartwheeled and came to rest inverted

- Pilot with 4600 hours of experience got low, tried to reach an airport, then tried to divert to a field, failed to clear trees on final

- Pilot with 200 hours of experience found himself in sink outside glide range of an airport; tried to land on a road and hit a sign

- Student pilot left glide range of airport, tried to land on a street and hit trees and a power line

- Pilot with 700 hours of experience continued to fly along ridge in insufficient lift, was forced to land in unsuitable field and ground looped

- Pilot with 200 hours of experience flew into unlandable area based on expectation that he would find thermals; had to land in 1000ft field surrounded by tall trees; impacted trees on final

- Pilot landed in corn field and destroyed canopy

- During a flight with a passenger, a pilot with 300 hours of experience flew over a large wooded area, got into sink and crashed into trees 2 kilometers away from the airport.

When flying above flat terrain and cultivated farmland, staying within glide range of a land-able field can be quite easy – land-able fields might be found every few miles in all directions. But in different circumstances it can be very challenging: e.g. the mountainous areas and deserts of the Western United States are often completely unlandable, and airports may be 50 miles or more apart. High terrain may be in the way between your position and the nearest landable area even though your flight computer shows it to be within glide. Severe sink may degrade the attainable glide ratio of a 40:1 glider to 10:1 or even less. Bad weather may move in and make your only landable area inaccessible, etc. Considering these challenges, I found it surprising that not more accidents can be traced back to this root cause.

Relying on an engine

Glider operating handbooks typically state that a glider’s self-launch or sustainer engine must only be regarded as a convenience and not as something that the pilot can rely upon. Pilots are advised to only attempt an in-flight engine start when they are within glide range of a suitable land-out field that can be easily reached even with the engine mast extended (which degrades the glide ratio to varying degrees based on the specific glider). The accident reports reveal that many pilots failed to heed that advice. The temptation to keep going because the glider has an engine is often too great.

These accidents are just special cases of the pilot’s failure to keep an airport or a land-able field within glide.

- Airline transport pilot with 26000 hours of experience relied on engine to cross mountain ridge under power; engine overheated; pilot continued in glide; got into sink and had to turn; landed on freeway and impacted a barrier

- Flight instructor with 2300 hours of experience tried to climb into higher terrain under engine power, engine power was insufficient, pilot failed to turn around, and landed in trees just before reaching airport

- Pilot with 4000 hours of experience flew too low into mountainous terrain; encountered sink that exceeded climb rate of glider and crashed into trees

- Pilot with 2370 hours of experience attempted to start engine above land-out field; engine did not start; pilot was too low for proper landing pattern and crashed into trees short of field

- Pilot of amateur-built glider relied on two simultaneously working engines for flight; 1 was designed for RC aircraft; 1 engine failed after takeoff; plane hit trees short of runway

- Pilot with 2500 hours of experience decided to attempt engine start before selecting land-out field; when engine failed, diverted to field; was surprised by and impacted power line on final

- Pilot failed to make timely land-out decision; extended engine, engine did not start; tried to land but stalled and spun in on turn to final from low altitude; in turns out the fuel line was closed

- Pilot with 1300 hours of experience tried to start engine, engine failed. Pilot impacted ground just before reaching a land out field.

- Pilot tested engine after winch launch; engine failed to start; pilot tried to reach land-out field but hit trees on approach

- Engine did not start; pilot with 250 hours of experience tried to reach airport; came short and poorly executed land-out

- Pilot with 1700 hours of experience launched on winch, then extended engine and inadvertently opened airbrake. Engine did not start. Glider stalled and spun in.

- Pilot returning to home airfield noticed that we was too low; tried to start FES engine but battery was depleted (it showed 20% remaining); crashed into building on final approach

Misjudging the Final Glide

Misjudging the final glide and coming short is also a special case of failing to stay within glide range of an airport or a landable field and in some cases it can also be viewed as a special case of delaying the decision to land-out (provided that adequate fields were available along the final glide route). These cases tend to occur more frequently in a racing context, especially when there is no minimum altitude to finish the race. (If you also fly Condor multi-player races you will be very familiar with this).

- Pilot with 3164 hours of experience misjudged final glide, tried to return to airport, diverted to alfa alfa field and ground-looped.

- Pilot misjudged final glide; tried to return to airport and crashed into trees short of runway

- Pilot with 1200 hours of experience misjudged final glide and hit trees on final approach

- Contest pilot with 700 hours of experience misjudged final glide and hit trees on final approach

Impacting Mountain – Failure to Maintain Sufficient Distance and/or Airspeed when Flying Close To Ridges or Mountains

Ridge running and mountain soaring is likely to be more dangerous than flatland flying although it is impossible to demonstrate this because there are no reliable data available that break down all soaring activities into flatland vs. ridge and mountain soaring. However, a significant number of accidents happen because pilots fly in close proximity to mountainous terrain and without maintaining extra airspeed. The most typical case involves a pilot circling below the top of the ridge or just slightly above it, then getting unexpectedly close to the ridge (e.g. due to unexpected sink / lack of expected lift), pulling up, stalling, and spinning in. The temptation to fly too close and too slowly is greatest in weak conditions when flying at a safe speed and at a safe distance from terrain can make it impossible to climb. Here are some examples:

- Pilot with 700 hours of experience thermalled at low altitude along the ridge, stalled and spun in. (The glider was equipped with a front electric sustainer that the pilot did not use, so it is unlikely that he believed himself to be in real trouble until the accident occurred.)

- Highly experienced pilot soared low above complex rocks and ridges and impacted terrain.

- Pilot circled next to mountain slope and stalled while heading towards the mountain; lowered nose to gain speed and impacted trees; very lucky to survive with minor injuries

- Pilot with 280 hours of experience flew low along ridge, got into sink and had insufficient energy to avoid terrain impact

- Pilot with 500 hours of experience circled below ridge line in windy conditions and crashed into trees on steep slope

- Pilot with 3500 hours of experience thermalled at low altitude along a slope in somewhat turbulent conditions, the glider stalled and spun in

- Pilot with 3900 hours of experience circled in weak lift low along slope, stalled and spun in

- Pilot with 760 hours of experience thermalled too slowly above slope, glider stalled and spun in

- Pilot with 400 hours of experience flew too low along ridge and collided with trees (could have been a stall/spin; details unknown)

Probably all of these accidents could have been avoided had the pilot followed the basic rules of 1) flying figure 8s instead of circling below the top of the ridge and until a safe distance to the top of the ridge is reached; and 2) maintaining extra air speed when flying close to terrain.

Flying into Clouds – Failure to Stay Clear of Clouds

These accidents tend to occur in wave flying conditions when pilots fail to make a timely decision to descend and the cloud layer closes below. Examples:

- Pilot was flying in wave and cloud layer below was closing rapidly; got into clouds and decided to exit with parachute

- Pilot on wave flight descended when cloud layer closed. ASW 27 reached high speed in cloud and broke up, possibly in rotor; pilot parachuted out

- Pilot probably flew into clouds, lost orientation and impacted terrain (cause is not clearly established)

- Airline transport pilot with 12000 hours of experience conducted a forbidden IFR flight directly into squall line thunderstorm, lost control and crashed

Other Decision Mistakes

The examples above account for the vast majority of all accidents that can be traced back to wrong in-flight decisions. Other decision mistakes happen as well but are quite rare. Here are some examples. All of them are one off occurrences.

- Pilot tried to cross a mountain ridge while flying under power. When he got too low, he pulled up, stalled and crashed

- Pilot decided to take off from wet, upsloping turf runway with quartering tailwind and high density altitude; the climb-out was too slow, glider released, tried to make 180 and impacted trees

- Pilot flew two aggressive low passes, then crashed on final 180 degree turn to land

How Can We Avoid “Fateful Decisions” And Resist Temptation?

To answer this question we must first consider that practically all decision mistakes in soaring are preceded by the temptation to do something that we know is objectively unsafe. (But somehow we are doing it anyway.)

There are three important factors at play that determine how hard it is for us to resist the temptation and do the right thing:

(1) how strongly we are tempted;

(2) how great we think the risk is;

(3) whether we have to take an active decision to to something that’s dangerous (e.g. deliberately fly low over unlandable terrain) or if the danger is coming at us and we would have to take an active decision to get out of it (e.g. deciding to switch from thermalling to landing in a field as we get closer and closer to the ground)

We are most likely to make a fateful mistake if the temptation is high; our subjective assessment of the risk is low; and if the risk is coming at us such that we have to take a pro-active decision in order to avoid it.

Consider the following (fictional) scenario: a contest pilot is in first place on the last day of a national competition. He knows that he doesn’t need to win the last contest day but he has to complete the task: landing out would not only cost him the overall win, he would most likely be off the podium altogether. He would also miss his chance to compete in the World Championships, something he has aspired to his entire flying career. In short: his temptation to avoid a land-out is about as high as it can be.

During the flight, he made a minor tactical mistake and on the final leg he finds himself lower than he would like to be. No big deal, he has been in this situation many times before. In his club he is well known for his flying skills. He has thousands of hours of experience and has never had an accident. In other words: his subjective assessment of his personal risk when thermalling close to the ground is likely to be fairly low.

As he keeps looking for lift he is surprised (and increasingly annoyed) that he gets lower and lower as he continues on course. All he needs is one good climb and he can make it home. Somewhere between two fields that don’t look great but are probably land-able he finally finds some weak lift. He is down to 450 feet. This has got to work! He has gained back 600 feet when the lift dies. He’s got to move on and there’s a newly forming cloud just ahead. This is perfect! There also seems to be some kind of field right there. He pushes for the cloud. He’s down to 400 feet again when he encounters lift. He turns. Dammit – wrong turn direction. That hardly ever happens to him. Why now?There’s some big sink – he’s down to 250 feet. The field is within reach but he notices a power line running through it as he tries to center the thermal. This lift is narrow! But it will work! While he tries to center the turn, flying close to stall speed to keep the turn radius as tight as possible, he also tries to get a look at the field and the power line to figure out how he would land should this become necessary. Suddenly there’s a gust from behind, the glider stalls and spins in. The last thing our pilot sees is the ground rushing at him. And he hasn’t even made an active decision to do something that’s risky!

(1) The Strength of the Temptation

When we fly we can be tempted either by our desire to achieve positive flight outcomes (e.g. a personal best, more OLC points, peer recognition) or by our desire to avoid negative outcomes (e.g. having to land out and losing a contest, losing peer respect, missing an important meeting).

Recognizing that “you will be tempted”, as John Cochrane puts it, is the first and perhaps most crucial step towards making better piloting decisions. As John writes, “it’s much wiser to realize that you will be tempted and start preparing now to overcome that temptation, rather than just pretend you’re such a superior pilot it won’t happen to you.”

In applying Prospect Theory to soaring, Daniel Sazhin explains that the two types of temptations – positive and negative – are quite different in terms of human psychology. “People take the biggest risks when they are confronted with losses rather than gains.” I.e., the temptation to avoid a negative outcome is much stronger than the temptation to achieve a positive outcome. That means, for example, that a pilot who wants to achieve a new personal best is significantly less tempted to take great risks (there will be another opportunity!) than a pilot who thinks that he will get reprimanded or ridiculed for landing out.

What really matters, however, is not so much the situation per se but how we as individuals think about it. If you are thinking of a land-out as something that you must avoid at all costs, it’s not surprising that you are likely to wait far too long before you decide to switch from thermaling into landing mode. But you can choose to think about it differently! E.g., one of my fellow pilots in Boulder thinks of land-outs as opportunities to have a great adventure. This is a great way of re-framing the same situation! Instead of being something to be dreaded, a landout becomes something positive. If you can convince yourself to think about it this way, you are much less likely to take great risks when you find yourself low above some farmer’s field!

(2) Our Perception of the Risk Involved

If we think that a particular course of action could put us in grave danger, we are obviously much more likely to resist the temptation than if we think that nothing will happen.

The problem is that most of the time we don’t actually know how risky a particular situation or maneuver is. Instead we rely on our own subjective risk perception. And our perception is primarily shaped by our own experiences.

This means, if we make decisions that rarely but regularly lead to disastrous outcomes, and which Martin Hellman calls 99.9% safe maneuvers, they will appear to us as less and less dangerous because each time we made such decisions “nothing happened”. A glider flies until is doesn’t and we pay no price for repeating risky behaviors over and over again until the one time when it is too late. That’s when we become complacent.

Daniel Sazhin explores the psychology of this in more detail in his article “Experience Can Kill You” where he illustrates why we are prone to underestimate the risks of relatively rare events especially when our decisions are based on past experience.

To stay safe, we must remain aware that dangerous situations and maneuvers are, well, dangerous.

(3) Risks That Find Us vs. Risks We Decide To Take

One way to look at soaring decision accidents is to examine if the pilot deliberately flew into a dangerous situation, or whether the pilot failed to make a timely decision that would prevent him or her from getting into danger.

The accident data shows that only very few accidents were caused by pilots who actively decided to get into potentially dangerous situations. One such accident happened after the pilot had flown two low passes and then stalled and spun in during the turn to land; one involved a pilot who decided to fly into a line of squall line thunderstorms; and two or three cases involved pilots who actively decided to continue their flights over unlandable terrain without keeping a land-able field in glide.

In the vast majority of cases, the pilot did not actively invite the risk; the risk found the pilot, and the pilot failed to make a timely decision that would have prevented the accident.

This is bad news for those who might have thought that accidents primarily happen to thrill seekers. That is simply not the case. There are some thrill seekers in this sport who deliberately lead dangerous lives, but they represent a small minority. Most accidents happen to pilots who are generally risk-averse.

Ironically, being risk averse might make us even more likely to get into an accident in situations where the necessary evasive action carries some inherent risk as well. This is particularly the case when we are low and confronted with a familiar dilemma: should we decide to land in a field and risk hurting ourselves; or should we keep trying to thermal and risk hurting ourselves? Our fear of botching the land-out just adds to the temptation to keep trying to stay aloft, and the temptation continues to grow the closer we get to the ground. We are inclined to delay and delay the decision to land until one way or another, it is too late and we crash.

To stay safe, there are two lessons here: first, we must remember that the risks will find us without us having to go looking for them. We must make the timely and pro-active decision to take preventative actions. Second, we must mentally prepare ourselves for the possibility of having to land in a field. This goes without saying for anyone flying cross-country but it is even true for those who intend to stay close to their home airfield. Remember: eventually the risk is going to find you!

Strategies to Avoid Fateful Decision Mistakes

John Cochrane, Daniel Sazhin, Martin Hellman, and many others have proposed various strategies and I have added my own. I don’t think that there is a single silver bullet that works for everyone. I suggest you pick the ones that will work for you or even develop your own. The key is that you are not only able to think about this while you are on the ground, but that you remain firm in your resolve when you have to make the tough decisions while in the air.

(1) Remember that you will be tempted and try to direct your mind to keep the temptation as low as possible.

- E.g., if you think of landing out as something to be dreaded, try to reframe your perspective and channel your mind to think about all the positive experiences that you can gain from it.

- It you’re flying in a contest, try to focus on the immediate activity to be performed (and not the day or the overall result). Be like a tennis champion who is able to stay focused on each point and not get wrapped up in thoughts about the set, match, or the championship. If the task before you requires a safe land-out, execute it like a champion would. If your mind wants to go back to the bigger picture, broaden your perspective further and think about your family and the many years of soaring ahead. Remember that today’s flight outcome is insignificant provided you stay safe so you can fly again tomorrow.

- I also like John Cochrane’s suggestion that you pick a hero story to help you reduce the temptation: he recounts the tale of his hero, John Seaborn, who refused to fly into a line of thunderstorms during the 2001 US Nationals, thereby forgoing the contest win and a chance to participate in the World Championships. Be like John Seaborn! (Btw: this story continued. At the 2018 US Nationals, John was in first place until the last day of the competition when he ran out of lift and executed a safe landout. Then, one year later, his patience paid off and he finally got his reward and won the 2019 US Nationals. Again: be like John Seaborn!)

(2) Regularly remind yourself that certain maneuvers such as thermalling low (even next to an airport), flying close to ridges without an adequate safety margin, circling below ridge-tops, crossing unlandable terrain (with or without an engine), low-energy final glides, terrain transitions at low altitude, etc, are – and will always remain – dangerous. This is true even if – and especially if – you have a lot of experience. Here are some things you can do to remind you that these risks are real:

- Regularly invoke your memories of situations when you scared yourself. How did you get into these situations and what are you doing differently now to prevent them from happening again? E.g., I write flight reviews with lessons learned to help me avoid repeating my own mistakes.

- Try to learn from the experience of others, especially those that have perished while giving in to temptation (e.g. by reading accident reports). Do not dismiss what happened to them by thinking that you are better then them. Instead, imagine how they got into these situations and how this might happen to you as well.

- Invite flight instructors and peers to critique your flying and tell you if they notice any risky behavior. Correct it before it becomes a habit and your brain tricks you into believing that repeating a dangerous maneuver makes it safer (it doesn’t).

- Recency matters so repeat those exercises from time to time. You can also ask yourself on every flight “what can possibly go wrong” and fly as if everything that could go wrong would come to pass.

(3) Plan ahead because the risky situations will find you and you will have to act to prevent them. Pre-plan the most difficult decisions so when the time comes, your mind is already made up and all you need to do is execute your plan.

- Decide what safety margins you will maintain. E.g. “I will keep a minimum distance from mountainous terrain of at least x wingspans and I will never fly slower than x kts; I will never attempt to thermal below x feet; I will not circle along a ridge until I am at least x feet above; I will always keep a landable field in glide with an arrival altitude of x feet and assuming a glide ratio of x:1 (or a MC setting of at least x); for final glides I will use a safety altitude of x feet and and MC setting of at least x; I will never extend the engine unless I am at least x feet above a landable field.” Write these safety standards down, and promise your spouse and your friends that you won’t violate them. Review your flight logs to see if you kept your promises.

- Some situations are less suitable for such simple decision rules because they require constant adjustments in flight. However, you can still make commitments that will help you stay ahead of the game and avoid the other frequent “fateful decision” mistakes. e.g. a good general rule is the familiar plan A/B/C paradigm: “whenever I decide to attempt something that is not 100% certain (e.g. a terrain transition, flying above unlandable terrain, approaching a ridge, soaring above clouds, etc.) I will always maintain a plan B and a plan C that I can fall back on if plan A does not work out.”

- Pre-planning is especially important for land-outs where our temptation to delay the decision is the greatest. Promise yourself that “when I am x feet above the ground I will land, and I will not change my mind”

- Note that the same set of rules will not work for everyone and everywhere. Your minimums should reflect terrain and site-specific considerations and must be appropriate for your glider and your skill level.

2) Basic Piloting Mistakes

This second category accounts for ~30% of Soaring Accidents. All of the skills necessary to avoid these accidents are regularly taught as part of basic flight instruction. You might ask, why then do these mistakes still occur? I had the same question.

One of the most interesting overall findings is that even the most basic piloting error accidents are rarely caused by true beginners!

In fact, only 10% of all improper aircraft handling accidents involve pilots with less than 50 hours of flight experience, and another 10% were caused by pilots with more than 50 but less than 100 hours of flight experience. The median level of experience of pilots involved in these accidents is 416 flight hours.

That means flight instructors overall do a pretty good job teaching the mechanical skills of flying. The main problems can be found elsewhere!

What leads even experienced pilots to make basic flying mistakes?

Once again, I’ve tried to look at these accidents based on the root causes that got the pilot into a situation where they were unable to react properly and steer the plane.

You might notice that many of these cases also involve some level of negligence or improper decision making. However, I classified all of them as “improper handling of the aircraft” because good piloting skills alone should have been enough to avoid the accident – even if the accident was preceded by carelessness and/or a poor decision.

I am discussing them in the order of how frequently they occurred:

Reaction to Emergency – Failure to React To Standard Emergency Situations

Pilots frequently run into trouble when they encounter a standard emergency situation that they have not personally experienced or trained for in a long time. Many of them occur during winch launches where an immediate reaction is required.

- The winch cable broke at 300ft AGL, the pilot was too slow to react, stalled and spun in

- Winch failed to pull at about 100ft AGL, glider stalled.

- Winch pulled too slowly, pilot stalled and spun in.

- Winch cable disconnected from glider, pilot stalled and spun in.

- Pilot climbed too steep on the winch, stalled and spun in.

- Wing of glider touched ground during ground roll, the pilot did not release immediately, the winch driver stopped the winch, the glider stalled and crashed

- The gear of a glider collapses on take off roll, the glider pilot did not release and launched, the winch driver stopped the winch, the glider stalled

Interestingly, pilots seem better prepared to deal with the clear-cut case of a standard cable break, than they are prepared to react to irregularities in the winch’s operating speed. If you think about it, this makes sense because we have trained for cable breaks and our reaction in this case is more instinctive. When the winch just slows down our instincts don’t work quite as well because our first reaction may be to hang on and figure out what’s going on. By then the glider may have already stalled and our reaction comes too late.

Extensive flight experience is not a good preparation for these types of emergencies. Hundreds of uneventful winch launches make us drop our guard because we are not expecting a problem. In fact, the data suggests that a student pilot who has just gone through cable break exercises is more likely to react correctly in these situations than someone who hasn’t experienced a winch problem in a long time.

Overconfidence and Complacency

Experienced pilots, even when somewhat rusty, are more likely than beginners to overestimate their flying skills. Here are some examples of accidents where the pilot’s plane handling skills perhaps weren’t quite as good as they thought. These accidents could have been avoided had the pilot been a little more humble and avoided maneuvers that required more proficiency.

- Pilot slipped plane into the ground, perhaps through a combination of overconfidence and show-offishness

- Pilot of motor glider thought he could land in a small field, touched down, tried to go around and stalled out during the attempt to clear the tress at the end of the field.

- Pilot decided to land with a tailwind out of convenience and loses control of the glider

- Pilot returned to flying after a longer break and was unable to control glider during a normal aerotow

- After crossing the finish line, a contest pilot decided to land directly rather than fly an abbreviated pattern. When extending the gear near the ground she inadvertently moved the stick forward and drove into the ground at a high speed of 100 kts.

Inexperience – Basic Piloting Errors By True Beginners

Of course there are several cases involving students who lacked the necessary training to react appropriately. Here are some examples:

- Student pilot (age not reported) had only theoretical spin training and did not know how to exit from a spin

- 17 year old student pilot on first solo flight started to oscillate at 1000 ft AGL and lost control of the glider

- 15 year old student pilot with 30 hours of experience lands far too fast, bounces and crashes

- A 76 year old student pilot observed and reported speed fluctuations on the winch but failed to lower the nose when winch slowed. The glider stalled and spun in.

Unfamiliar Aircraft – Insufficient Familiarization with New Aircraft

Several accidents happened after experienced pilots transitioned to an unfamiliar aircraft. Their experience might have contributed to making them less diligent in acquainting themselves with their new equipment. Several of the cases happened after a transition to a more complex motor glider.

- Pilot flew a new aircraft, stalled and spun in during winch launch

- Pilot flew new motor glider and failed to retract the engine. Pilot did not appreciate the degraded glide ratio, flew landing pattern too low and too slow, stalled and spun in

- Pilot forgot to open fuel line on motor glider, over stressed, and crashed

- Pilot flew historic aircraft too slowly, stalled and spun in on final approach

- Pilot with 1700 hours (age 61) failed to notice that he mistakenly opened the airbrakes when extending the engine, over stressed when the engine did not start, stalled and spun in

Inattention

Experienced pilots are likely more relaxed than beginners. While this means that they are less likely to suffer from tunnel vision, the downside is that it can also make them less attentive. Four of these accidents happened when the glider pilot did not pat attention and accidentally climbed too high on tow.

- Pilot did not pay attention on tow and climbed high above tow plane right after takeoff. Luckily, the rope released on its own and the tow pilot remained unharmed. The glider pilot turned to the left and impacted the ground.

- Glider pilot with 1300 hours of experience climbed too high on tow and drove towplane into the ground.

- Glider ballooned after takeoff on aerotow, pilot failed to release in timely manner, and pulled tow plane into the ground

- Glider climbed too high on tow, tow-pilot released; glider touched trees

- Pilot did not account for headwind on final approach and landed short.

How Can We Avoid Basic Piloting Error Accidents?

Basic piloting errors should be relatively easy to prevent. However, since most of them happen to experienced pilots, who likely consider themselves to be least susceptible, the biggest obstacle to reducing their numbers is likely complacency.

Before we are willing to do something to address this risk we must first believe that it is us who are vulnerable! Once that is accomplished, the remedy itself is relatively easy.

(1) Regularly practice standard situation emergencies such as rope breaks spin entries, and irregular occurrences, especially on tow

E.g., if you have not had a winch failure or an aero tow failure in some time it’s a good idea to fly with an instructor and have them pull the release on you when you least expect it. Ask to also practice unexpected things such as a power reduction of the tow plane or an irregular winch speed. These emergencies happen close to the ground and require immediate recognition and an almost reflexive reaction. If we are stunned by what’s happening and are trying to figure out what is going on, the glider might have already stalled and it is too late. Recognizing spin entries is easy to practice on our own at altitude (as long as you really know what to do if the glider does spin in and you first make sure that there’s no one else below you. Practice with an instructor first if you’re not 100% certain.) The important thing is that we instantly recognize what’s happening and reflexively do the right thing to stop it.

(2) Really get to know your equipment.

When you transition to a new glider be as diligent as you were when you transitioned into your first single seater. Do not underestimate the complexity of your new glider, especially if it has an engine or other unfamiliar controls and instruments.

(3) Stay current.

If you have taken a break from soaring for a few months, take a check ride with an instructor before you get back into your own ship. Read the operating handbook again and make sure you know exactly how everything works before you move the glider onto the runway.

(4) Worry – at least a bit.

If you tend to feel very relaxed when you get into the cockpit ask yourself what could go wrong: think of traffic, wind, weather, equipment failure, etc. Imagine the worst and how you would handle it. This will make you pay attention.

(5) Stay humble, seek critique, and critique yourself.

Reflect back after every flight: what did you do well? what could you have done better? what was the most dangerous situation? what could have happened in the worst case? what could you have done to avoid it? When you fly with an instructor, ask them to be ruthless in critiquing your flying. If we develop bad habits (and we all do), chances are that we won’t notice until someone tells us.

3) Pre-Flight Negligence

12% of all soaring accidents are the direct consequence of things that the pilot did or did not do before they even took off. In other words: once the launch process was underway, even the best piloting skills might not have been sufficient to prevent an accident. The chain of events that led to the bad outcome was already in motion.

Once again, these accidents happen primarily to experienced pilots. In fact, 85% were caused by pilots with at least 100 hours of experience and the median flight experience of the pilots involved was 700 hours.

Almost all of these accidents fall into a few groups, listed in order of frequency of occurrence:

Failure to properly assemble the aircraft and/or conduct a Pre-Flight and Positive Control Check (PCC)

The most frequent of these types of crashes involve disconnected control surfaces (mainly elevators or ailerons) and most could have been detected through a proper PCC. Examples:

- Pilot forgot to connect elevator and released after takeoff from aero tow. In this winch case, the pilot luckily made it to the top of the launch and exited with the parachute. In this case, the pilot crashed into trees after releasing from aerotow when he noticed the mistake.

- Pilot forgot to connect the ailerons on an SZD 30 Pirat. The same happened with this Nimbus 3T, this Astir CS, and this LS3a.

- The pilot of the tow plane forgot to remove the aileron gust locks prior to launch and crashed after takeoff. The glider pilot was able to release and land straight ahead.

- A glider pilot had deliberately removed the backrest. When the winch accelerated the pilot was pushed back into the soft seat cushion. His arm was too short to push the stick forward enough to keep the nose down. The glider stalled and spun in during the climb and crashed.

- In this case, the rudder hinges were corroded and the rudder fell off the glider.

Failure to consider a specific pre-take off emergency plan before launch

We were all taught to have a pre take-off emergency plan in place before each launch that includes what we will do in case of an emergency. Unfortunately, as we experience one uneventful takeoff after another, we tend to become complacent and ignore or forget that lesson. Sometimes we maintain a vague plan but it is not specific enough and does not cover all eventualities. The problem is that if a take-off emergency does occur there is usually no time to think. We find ourselves at a low altitude and in a situation where flying a normal landing pattern is impossible. We may even be too low for a 180 degree turn and a downwind landing. The land out options at the airport we are flying from might be poor and we may not have reviewed them in some time (or maybe not even at all). We’re also over-stressed which means that neither our decision making skills nor our flying skills are as good as they would otherwise be. And every second we lose altitude and our options get worse.

Many of these accidents could have been avoided had we already pre-decided what to do. But without a clear and specific plan in place we tend to waver and wander about until it is too late. Examples:

- Pilot attempted 360 degree pattern after release at 450ft. Impacted trees on downwind leg. A 180 degree turn followed by a downwind landing would have been a much safer choice.

- Pilot on winch launch took off too early, touched back down after 150 ft, failed to release, stayed on tow, stalled, and crashed.

- Winch cable broke at 350 ft, pilot wavered, wasted time and altitude when there was room to land straight ahead, then tried to make 180 degree turn from the middle of the runway with nowhere to go, stalled and spun in.

- After aerotow release at 140ft, pilot failed to land straight ahead (despite there being plenty of room), tried to to make 180 degree turn, stalled and spun in. Here’s another similar case.

- Tow plane was unable to climb (in part because glider had flaps in landing configuration), the glider pilot failed to release on time and impacted terrain.

- A wing touched the ground during winch ground roll. Pilot failed to release and cartwheeled into the ground.

- Winch cable broke at 150ft. Instead of landing straight ahead, pilot hesitated, wavered, made several turns in both directions, stalled and spun in.

Failure to review the pre-takeoff checklist

These accidents typically involve either the canopy or the air brakes opening during takeoff. Examples:

- This airline transport pilot with 24,000 hours of flight experience took off without closing the canopy and airbrakes.

- In this case the canopy opened on the downwind leg. Due to increased drag the pilot landed short of the runway.

- Canopy opened on aerotow at 300 ft. Instead of staying on and flying the plane, the flight instructor released and slipped into ground.

Failure to properly prepare a Cross-Country Flight

A few accidents (all in the American West) involved flights where a landing place shown on a map did not exist or could not be found by the pilot.

- Pilot was unable to locate an unimproved airport and had to land on an unsuitable dirt road.

- Pilot landed on a closed runway and hit a fence.

How Can We Prevent Pre-Flight Negligence Accidents?

Similar to accidents caused by poor basic piloting skills, these accidents are easily avoided if we realize that we are susceptible and are willing to be consistently diligent in our flight preparations.

(1) Always use and follow checklists.

The most important ones are: assembly checklist; pre-flight check including PCC; pre-take off checklist; pre-landing checklist. Start over if you get distracted. Never ever skip the PCC!

(2) Have an emergency plan for each takeoff.

Be very specific and consider all eventualities. E.g., what do I do during ground roll if: the wing touches the ground; the towplane won’t climb, the winch slows down. Once airborne, what do I do if the rope breaks or if the tow plane/winch fails at different altitudes. For me, the best tactic is to actually call out loud what I would do “now” if the rope were to break: e.g. land straight ahead; small field 90 degrees left; larger field 30 degrees left; 180 degree turn to the left. This way I know exactly what to do and can focus entirely on executing the plan that is already in place.

(3) Never fly into the unknown.

Even if the sky ahead looks great! You must positively know before the flight where you can land. Also: always keep a landable place in glide.

4) Accidents Caused By Insufficient Situational Awareness

About 6% of accidents are caused at least in part by a pilot’s failure to maintain situational awareness either through audiovisual observations and/or (radio) communications. Most, but not all, of these accidents are mid air collisions that could have been avoided.

Failure to Maintain Visual Awareness

- A glider pilot with 3700 hours of experience on final approach did not observe a winch launch and collided with the falling winch cable during landing

- Two glider pilots flying in the same thermal ignored the Flarm warning signals and collided; all were able to parachute out.

- Two glider pilots were flying together as a team and were in the same thermal at 4000 AGL – no other gliders; they lost sight of each other and collided; one pilot was able to parachute out; the other was unable to exit the cockpit (glider had lost part of one wing and spun uncontrollably)

- Two glider pilots were flying in same thermal and aware of each other; then one repositioned the circle, they lost sight contact and collided in 2000ft AGL; one parachuted to safety, the other was unable to exit in time.

- During a contest, 10-15 gliders were thermaling in the same lift; one repositioned circle and collided with another glider at approx. 3000ft AGL. Only one was able to exit. (A Discus had lost one wing and was in spiral dive; it’s pilot could not exit)

- An aerotow rope (connected to a tow plane) lay across a winch rope; when glider launched on the winch the two ropes got entangled. This caused glider to crash.

- Glider pilot launched on winch and failed to notice that another winch cable was lying across to the ground roll path. This other cable hooked onto the tail of the glider at takeoff and pulled the glider into the ground.

Failure to Communicate

Many of the following accidents could have been avoided if the pilots involved had been communicating more pre-actively and/or listened more carefully to the communications of others. Here are some examples:

- Collision between power plane and glider on final approach; neither pilot had communicated their pattern entry and both were unaware of each other.

- Mid air collision between glider and ultra-light power plane. Glider pilot parachuted. Power plane was able to land. Neither was aware of the other.

- Glider and Cessna collided on final approach; both were able to land. The glider pilot was aware of the power plane but the power pilot was unaware of the glider. Both pilots relied on communications from ground operations. A direct communication from the glider pilot may have averted the accident.

- A glider and motor glider collided several feet above ground; neither had been aware of the other until that point; pilots were very lucky to escape unscathed

- A glider collided with a jump plane; neither was aware of the other; six people died on impact.

- A glider on final approach collided with a gyrocopter that had just taxied onto the runway. The glider pilot had seen the gyrocopter during pattern entry but then concentrated on landing and lost sight.

- Glider pilot failed to communicate that he carried water ballast; tow plane took off at normal speed; glider pilot noticed softness of the controls, assumed something is wrong with the elevator, released after takeoff and initiated ground loop before end of runway.

How Can We Prevent Insufficient Awareness Accidents?

The simple answer is to always pay attention, maintain a good look-out, and communicate pro-actively. That is true but probably insufficient advice. We can’t tell from the accident reports why the pilots did not do those things. It’s probably safe to say that we should

(1) Only fly when we are healthy and well rested so that we are able and willing to pay attention

(2) Ensure that our eyesight and hearing are up to the task. This is particularly important in countries (such as the United States) where pilots do not need a medical to fly gliders.

(3) Train ourselves to make regular position announcements on the radio, especially when we approach or fly in areas where we expect other air traffic. We must consider that glider pilots tend to seek out the same energy lines and are therefore frequently cruising towards each other at high speeds and at similar altitudes when it is close to impossible to see one another.

(4) Equip our gliders with compatible collision warning technology, especially when we fly in areas with other glider traffic. This could have prevented several accidents and probably has already prevented numerous others.

(5) Speak up when we notice something that could get others into trouble even if we’re not directly affected. This includes reminding others to pay attention or to communicate when we notice an opportunity for improvement.

(6) Pay close attention not just in the air but also on the ground.

5) Unavoidable Accidents

Like with any activity that involves dangers we must face the fact that some accidents really cannot be avoided by the pilot (unless of course they avoid to fly at all).

Fortunately, they represent the small minority of the cases. My analysis shows that approx. 8-15% of all accidents could not have been averted by even the most proficient and diligent pilot.

Most of those fall into one of the following four categories (in order of frequency of occurrence)

Technical Failures

These are rare but they do happen from time to time. I found this to be the cause in 9 out of 247 accidents (3.6%). This does not include issues that could have been detected by a thorough pre-flight check or failures that were caused by operating the plane outside its limits. I’m also not counting cases here where the engine of a motor glider failed to start. Here are some examples:

- In this relatively recent case, the rudder of an Arcus got uncontrollable at 17,000 feet causing the glider to enter an irrecoverable spiral dive.

- In this case, a wing of a Duo Discus broke in mid flight at a perfectly normal operating speed due to a manufacturing defect.

- And in this case, the connection between the controls and the elevator of a DG100 disconnected inside the fuselage after takeoff, making the plane uncontrollable.

Medical Conditions

Medical conditions that result in the pilot passing out during the flight could only have been prevented by the pilot not flying at all.

- There were at least four cases where the pilot suffered an in-flight heart attack. Here’s an example.

Certain Midair Collisions

Some midair collisions are avoidable through pro-active radio communications and better situational awareness. I have covered those under point 4) above. However, there are midair collisions that even the most diligent glider pilots would probably not have been able to prevent. These include cases where the other aircraft involved was not equipped with collision detection technology.

- In this extreme case a glider was hit from behind in Class E airspace by a military aircraft traveling at 410 kts.

- Multiple cases exist – such as this one – where two gliders collided head-on and where it was also practically impossible for one to see or take note of the other before it was too late.

Human Mistakes of Third Parties

In some cases an accident is caused by someone else and there is really nothing the glider pilot could do to avoid it.

- One such case involves a winch launch, where a crew member incorrectly attached the cable in such a way that it could not be released by the glider. Unfortunately the winch cable cutter was defective as well and the pilot had to try to land while remaining attached to the winch.

Methodology

Accident reports often just present what is known about the facts of an accident and sometimes even that is very little. In the case of fatal accidents there may be no witnesses. And in other cases, the accident pilot may have had an incentive to rationalize their own mistake(s) and attribute the accident to bad luck.

To understand how we can prevent accidents we have to get to the underlying reasons. In particular, I wanted to identify if the pilot had made a mistake or lacked basic skills that made it impossible for him or her to avoid the accident. This requires an act of interpretation, which is of course at least somewhat subjective. Obviously, no one can really know what went on in the pilot’s mind and in many cases, there are several contributing factors and sometimes a series of mistakes that led to the accident. However, after reading and re-reading so many accidents, clear patterns emerge, and I believe a reasonably accurate interpretation is possible. Someone else might interpret any one individual accident differently, but they would likely arrive at the same themes.

After interpreting each accident, I analyzed and categorized the results to develop recommendations and strategies of what each of us can do to minimize the likelihood of becoming part of the accident statistic.

Conclusions

As I pointed out at the beginning, once every 50,000 flight hours a soaring pilot dies. For every fatal accident there is also at least one accident with injuries. That means serious accidents where people are harmed happen about once every 25,000 flight hours.

The fatality rate of our sport makes it 2x as dangerous as riding motorcycles and 40x as dangerous as driving cars.

However, a careful analysis of accident reports shows that soaring does not have to be so dangerous. Approx. 90% of accidents are avoidable. If we were successful in doing that, we would reduce the risk of the sport by an order of magnitude such that it would only be 4x as dangerous as driving.

Unfortunately, such a dramatic reduction of accidents is unlikely to happen. However, each of us has an opportunity to drastically reduce the risks for him- or herself.

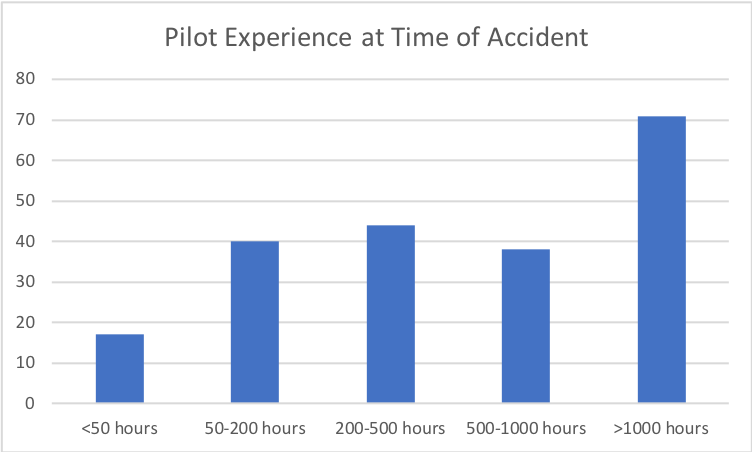

If you have read this entire post you have already realized that there are no silver bullets. You also know that experience alone is certainly not sufficient – in fact, it probably works against you. The median experience of the pilots involved in all these accidents is 522 hours. 34% of the accident pilots had flown more than 1000 hours. The following chart shows the distribution:

Here is a summary of the things you can do to help reduce your risk. I have organized them based on the types of mistakes that caused the most accidents, and the recommendations are listed based on my assessment of which ones are likely to have the biggest impact.

40% of accidents are caused by “fateful decisions” and “eroded margins”. Most of them are made by generally conservative pilots, not by daredevil thrill-seekers. How you can avoid them:

(1) Remember that you will be tempted to do something that’s dangerous and train your mind to keep the temptation as small as possible, e.g. by reframing potentially negative outcomes that you want to avoid at all cost (such as landing out) into positive opportunities (e.g. to have an adventure).

(2) Regularly remind yourself that certain maneuvers are always dangerous and that they do not get safer with experience. You may even be performing some of them regularly and no longer think of them as dangerous because nothing has ever happened. This is a dangerous trap that you have to get yourself out of!

(3) Pre-plan the difficult decisions such as when to stop thermaling and start landing; what you will do and not do when you’re in weak lift along a ridge, when to interrupt a final glide, etc. Your mind should already be made up when you get into these situations so you can focus on executing your plan.

30% of accidents are caused by basic piloting errors. Contrary to popular belief, even basic mistakes are most often made by experienced pilots. How you can avoid them:

(1) Regularly practice standard situation emergencies such as rope breaks and spin entries but also power reductions on tow and irregular winch speeds. We tend to be too slow in responding to situations that require a reflexive reaction if we have not experienced them in a while.

(2) Really get to know your equipment. Transitions to new and more complex gliders (e.g. motor gliders) often causes serious problems.

(3) After a break from soaring take a check ride with an instructor before you get back into your own ship.

(4) Worry – at least a bit. If you’re too relaxed there’s a real risk that you become inattentive. E.g., several people have dies because the glider pilot did not pay attention on tow.

(5) Stay humble, seek critique, and critique yourself.

12% of all soaring accidents are caused by Pre-Flight Negligence. The median pilot experience was 700 hours. How you can avoid them:

(1) Always use and follow checklists. Never ever skip the PCC or the Pre-Takeoff Checklist!

(2) Have a very specific emergency plan for each takeoff that covers all the things that could go wrong. “I can turn around at 200 feet” is very often not enough!

(3) Plan your flight, know where you can land, never fly into the unknown.

6% of accidents are caused by insufficient Situational Awareness. Most of these accidents are mid air collisions. How you can avoid them:

(1) Only fly when well rested so you can pay attention to the sky and the radio.

(2) Ensure that our eyesight and hearing are up to the task.

(3) Make regular pro-active position announcements when flying in areas with other air traffic. Expect other gliders to fly along the same energy lines.

(4) Equip your glider with Flarm and other traffic awareness technology.

(5) Speak up when you notice something that could get others into trouble.

(6) Pay close attention on the ground as well.

A masterpiece, congratulations and thank you!

Alvaro

where in the US do you live?

Would love to have you come and talk to our glider club if possible

Tank you for this, Well done and thorough. I hope you don’t mind if I translate in French and post on our website, I will mention origin of the article.

Salut Marc, bien sûr tu peux traduire l’article. Merci pour tes efforts! S’il te plaît envoie-moi un link lorsque tu l’as publié. Amicalement, Clemens

Congratulations for your excellent and exaustive paper. Your formula “the risk of dying doing what we love” is excellent, because it is a question in which the answer is inside the question !

It is because soaring gives pleasure in our lifes that we don’t want to associate it with the idea of death : how can we ? When the sky is full of little cumuluses, and that you are driving to your favorite little airfield, from which you will take off to reach a marvellous sky, how can you think in the same time that you may find death ? Almost impossible ! Really ? Yes and not. If you are in the Air Force for instance, you are constantly told that if you do this or that, you can die or get injured. This airplane hangar or this meeting room has the name of a dead pilot. There is a culture of risk. Death is put in front of you each time when necessary in the Army. Not very agreable, but very helpfull ! Now think of gliding : i practiced gliding some years, and i noticed that danger had not the same place… How to attract new pilots telling them they can die ? How to mix pleasure and death ? That is quite a challenge, and it is as complicated as it has been to explain to generations why, with AIDS, what gave life and pleasure could also give death. A good cause anyway.

Fantastic article, if just every glider pilot would concentrate on paying attention to half the things you propose…, this beloved activity would become a great deal much safer.

Go on like this!

I have been soaring already 55 years. Mainly over Austrian, Italian, Swizzerlands and France mountains and could accomplish several 1000 km cross country flights. Unfortunately I have lost some friends due to lethal accidents by soaring, therefore I understand very good your very interesting articel. Investigation of “What causes accidents” is the first step for avoiding most of them. In my book “Faszination Gebirgssegelflug”, Motorbuchverlag, ISBN 978-3613041912 there is a chapter “Gefahren (Danger)” but I will give this chapter more attention in my next book.

Excellent article, Clemens!

I would like to add to the Over-confidence issue.

In Paraglidng, we often referred to someone that: “Knows just enough to be dangerous”.

In other words; they are over-confident in their own abilities and do not have the experience to back it up, or even realise the risk of their actions.

Also known as the Dunning- Kruger Effect : >>

https://www.intelligentspeculation.com/blog/the-dunning-kruger-effect

Because, when you’re living on “Mt. Stupid” you don’t even realise it, it is important in a club environment, that the pilots that does have the experience will mentor someone that are taking too many risks due to over-confidence.

I’m that guy! Career powered pilot for over 40 years and just now getting into soaring. I have about 15 flights now and hope to solo here in a week or two up in Boulder. Your blog is very well received and is helping me develop my own set of personal minimums and operating standards that I’m hopeful will lead to a safe and rewarding experience with this new, to me, venture. Thanks for the effort you put into this!

Brilliant article

I will post it on our club Flight Ops.

Thank you!

Thanks for writing this Clemens.

Very informative especially to me with just 30 odd hours total gliding.

The unnecessary risk category… if your in it and you choose to ignore it, then your in it up to your neck all ready!

Thank you Sir, fly safe

George