Yesterday, CX scored 350 km in 2.5 hrs for the OLC Speed League, commenting, “today was probably the best cross country day out of Boulder since last September. The convergence was strong and well defined to the North and workable to the South. Unfortunately there was only one flight posted for League scoring.”

I had a fun flight too, but it was all down low and in terms of league scoring? – Nothing! And it’s not that I didn’t try. So I thought I’d try to look at my flight versus CX’s and find out what happened.

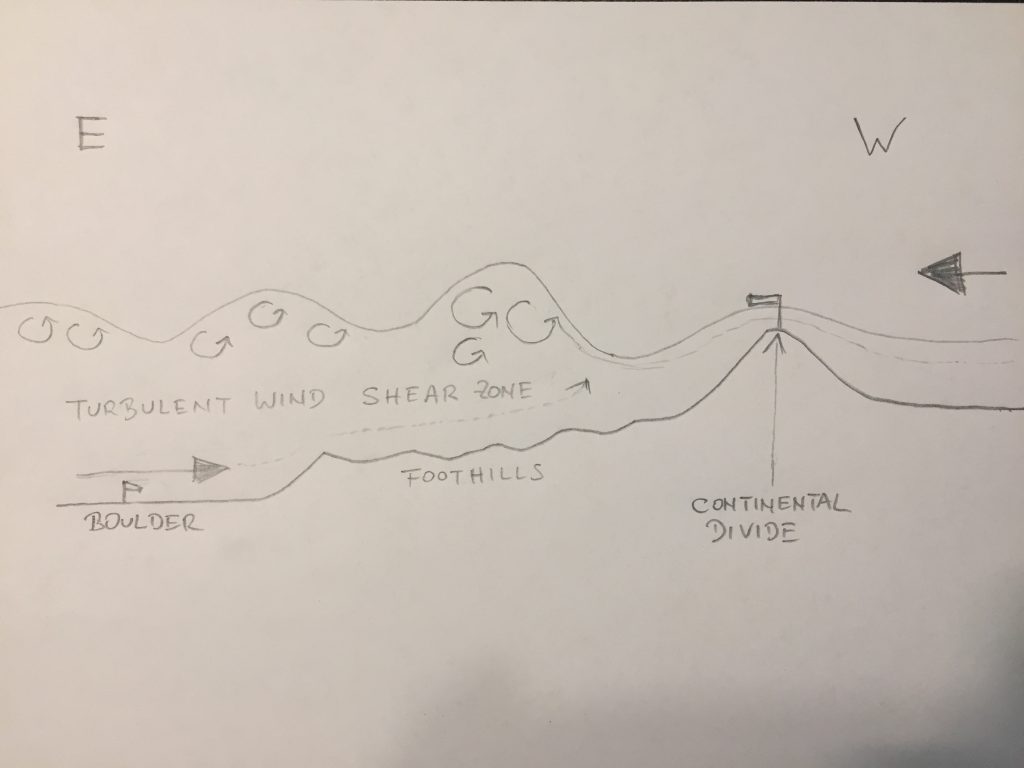

First, let’s recap the conditions. There were very strong westerly winds coming across the Continental Divide. And there was a weaker easterly flow approaching the mountains from the plains. (You could see it at the airport in the morning: there were low clouds moving westwards and building up a stratus layer that later burned off. A few thousand feet higher were rotor clouds that were rapidly moving east with obviously significant wind-shear between the two layers.

These conditions are very frequent at Boulder so it’s important to try to form a mental picture of what was going on. The following is a simplified illustration of how I see it. (This could be wrong but it pretty much matches my still limited experience.)

The trick to high XC-speeds is to find the place where the easterly and the westerly flow converge, i.e. the air is pushed up, and then to follow this line as you fly north or south, usually somewhat parallel to the mountains.

Fast XC speeds aren’t the only reason to look for the convergence line. The air on the west side of the convergence is almost always dryer and clearer (less hazy). This means the ground can heat better, the thermals will be stronger, they will develop earlier, and they will reach higher. Soaring on the west side is almost always better than soaring on the east side, especially in the morning when there is often a ground inversion in the valley that has to burn off before thermals can develop at all.

The differences in air quality to either side of the convergence also mean that clouds will look different. Most notable is the difference in cloud bases – they tend to be noticeably higher on the west side. So if you see a step in the cloud base, always try to stay underneath the higher base to the west. You may also see scraggly looking curtain clouds along the convergence line. Stay just to the west of these clouds and you should be in the area of good lift.

Back to yesterday’s flight. I knew there was a strong convergence line but I didn’t get into it. Why?

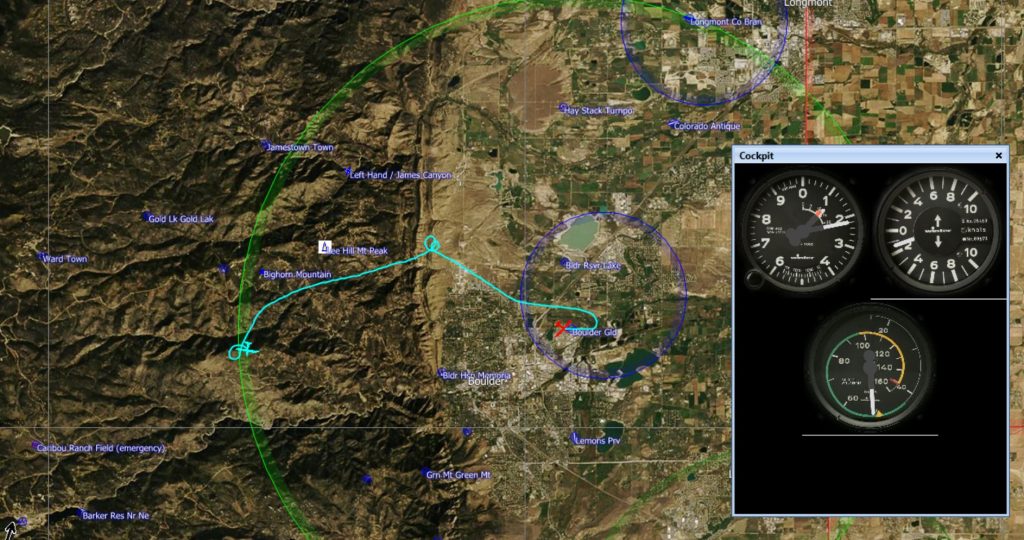

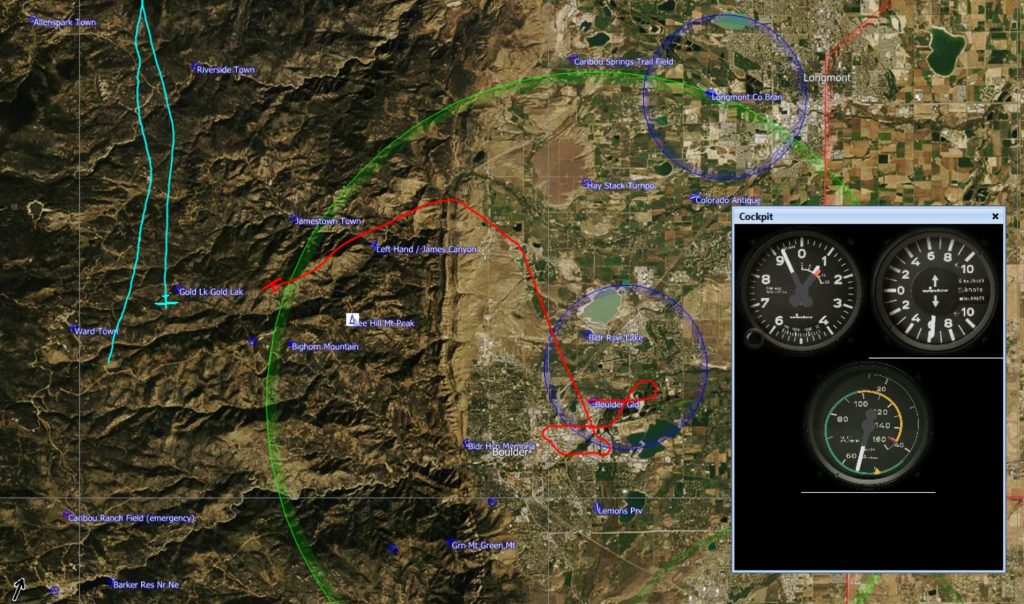

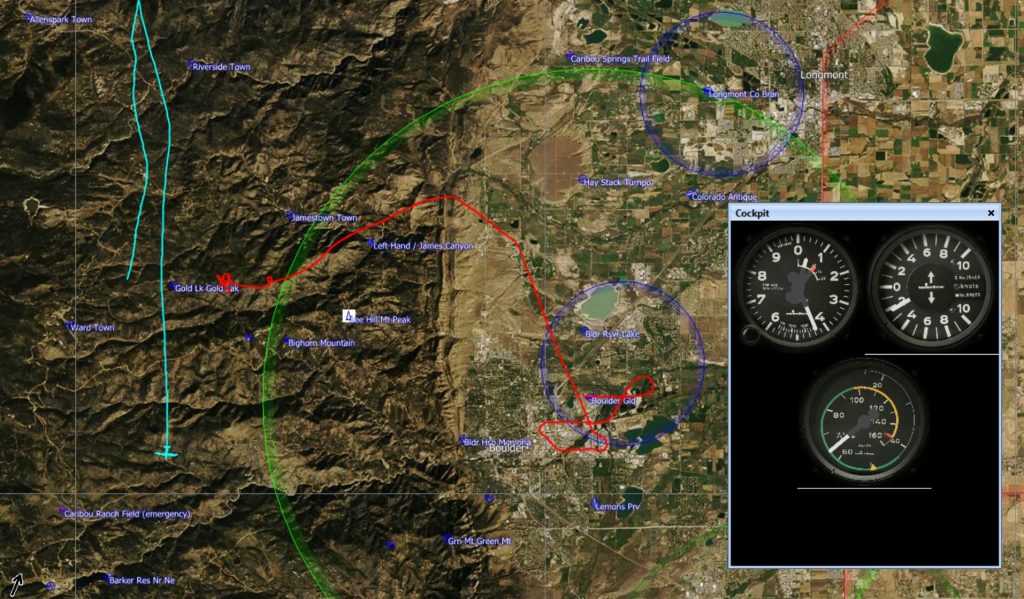

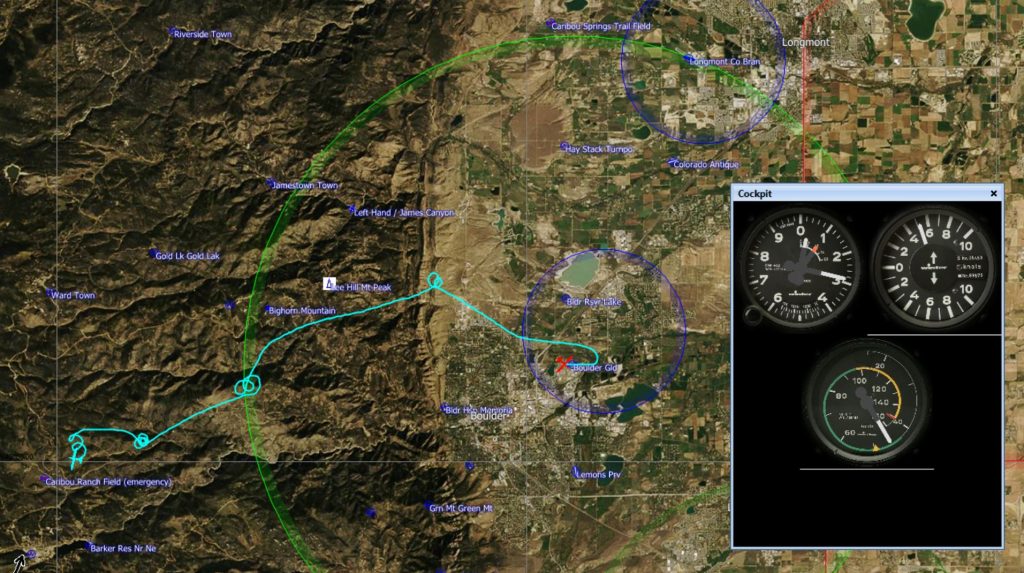

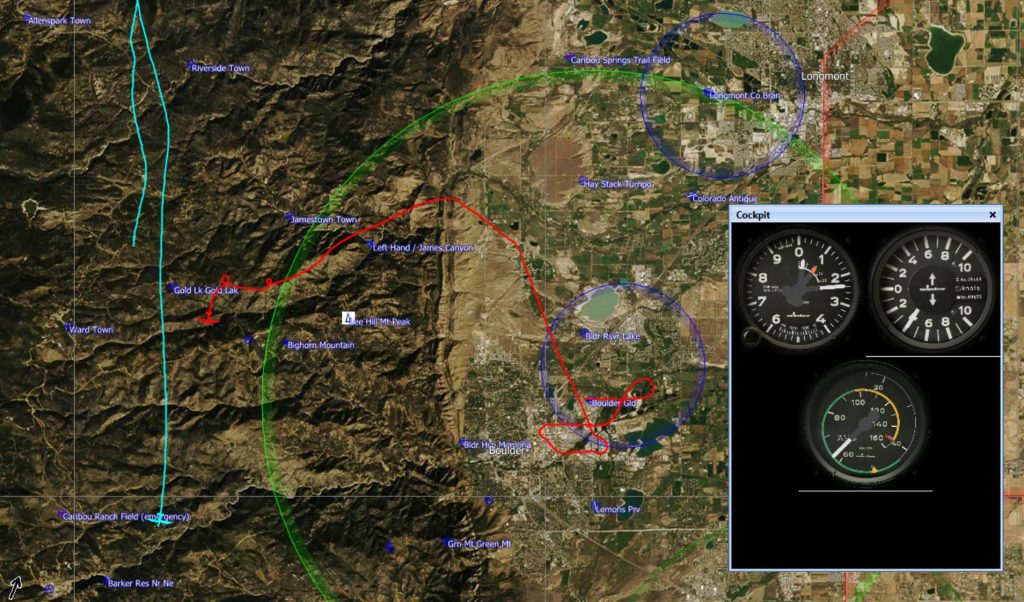

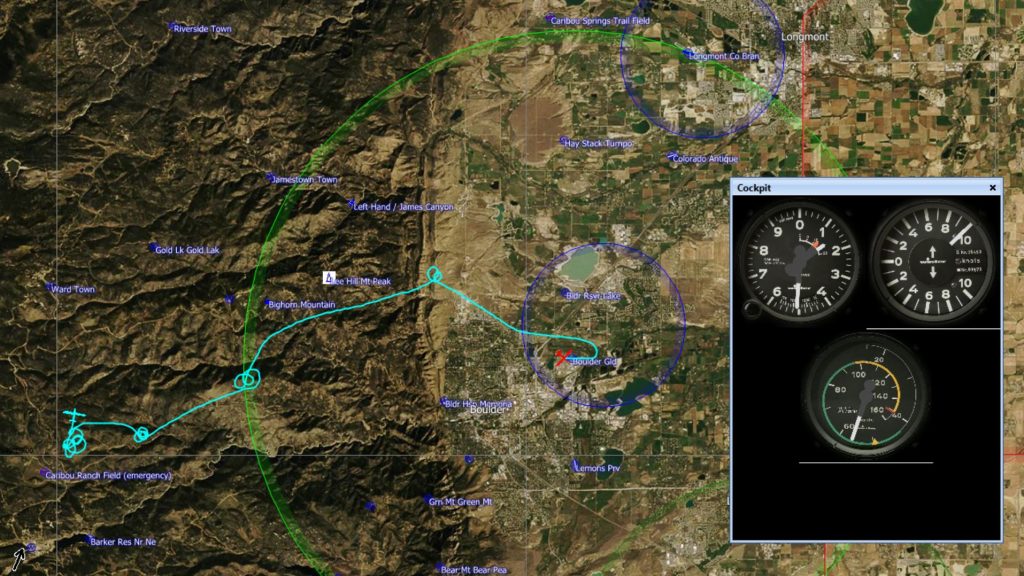

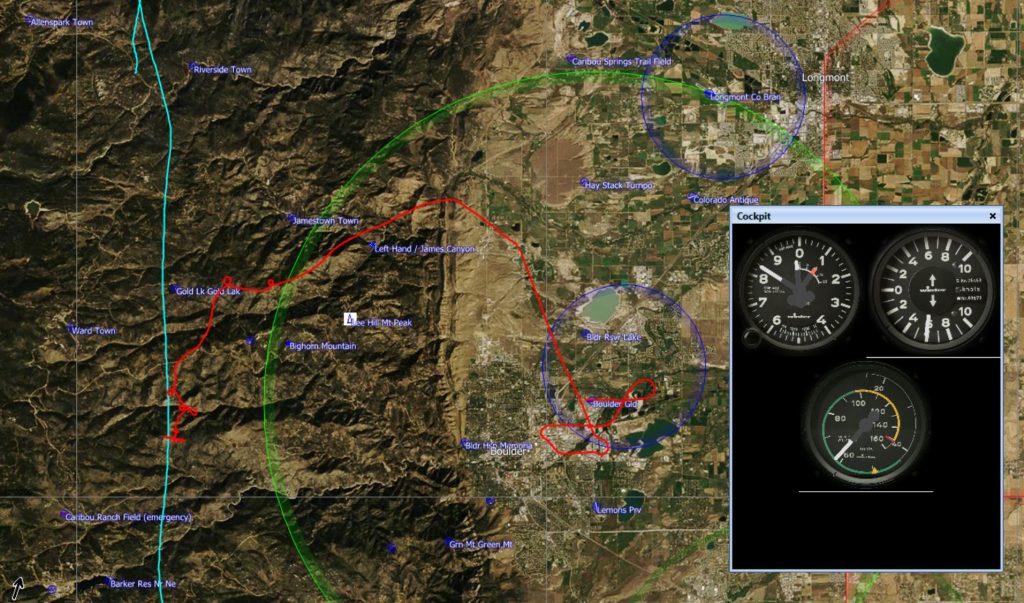

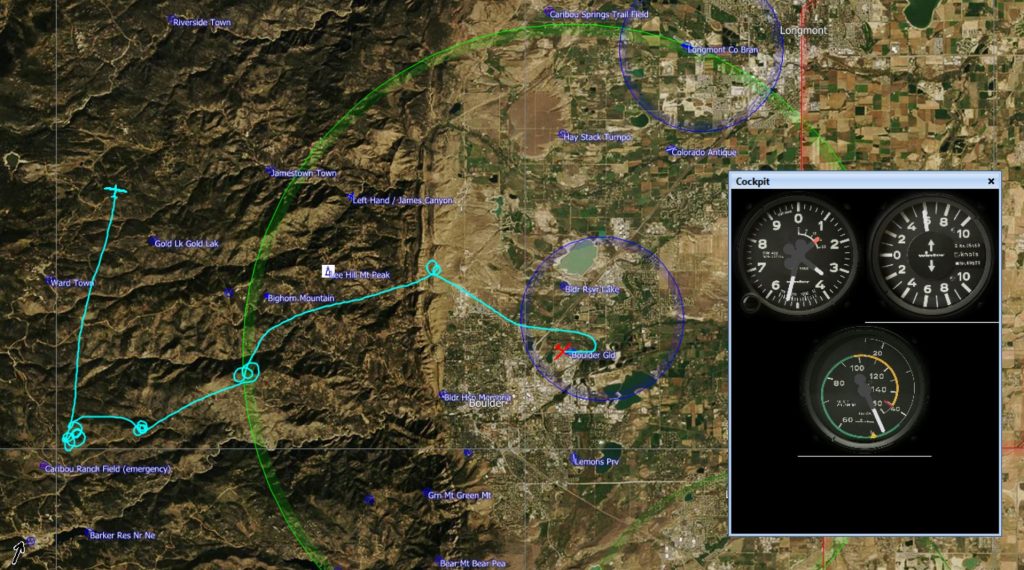

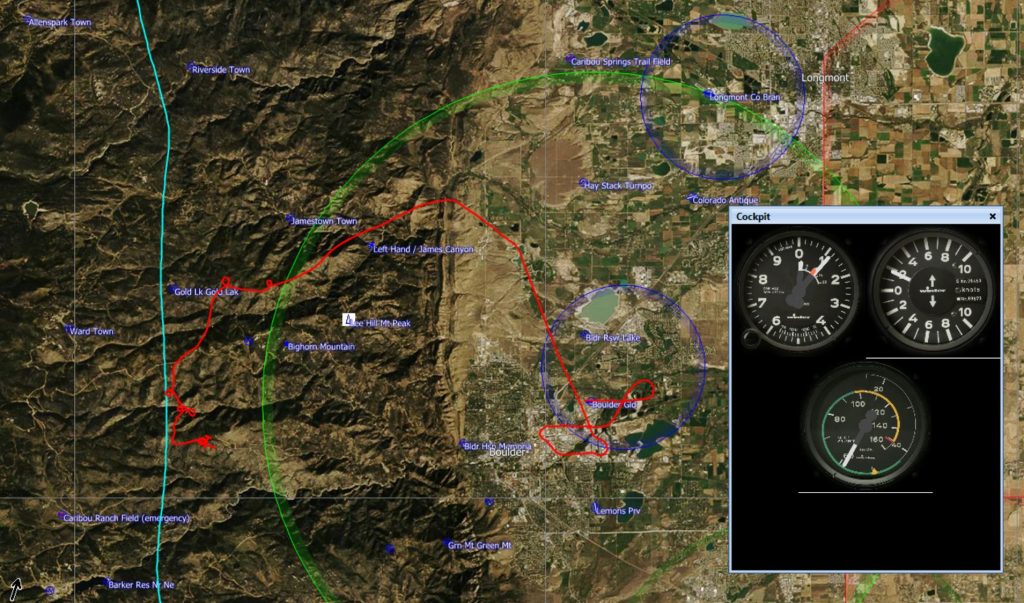

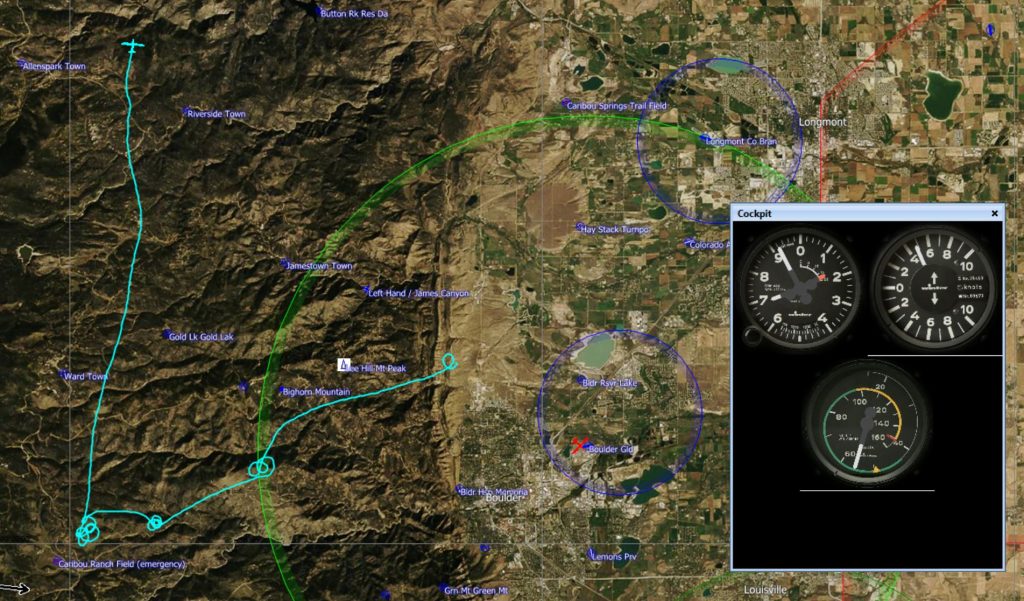

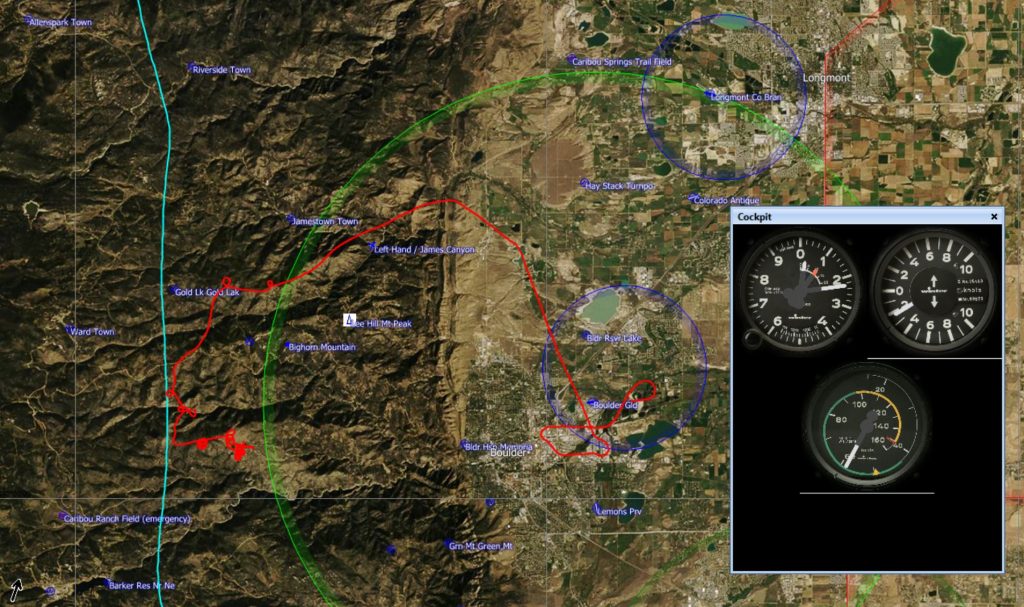

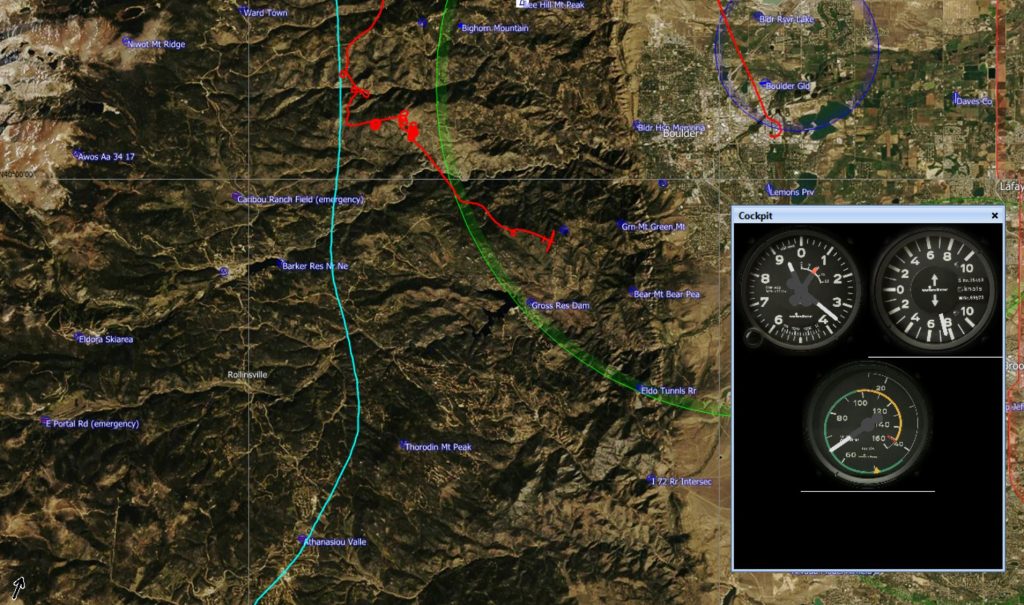

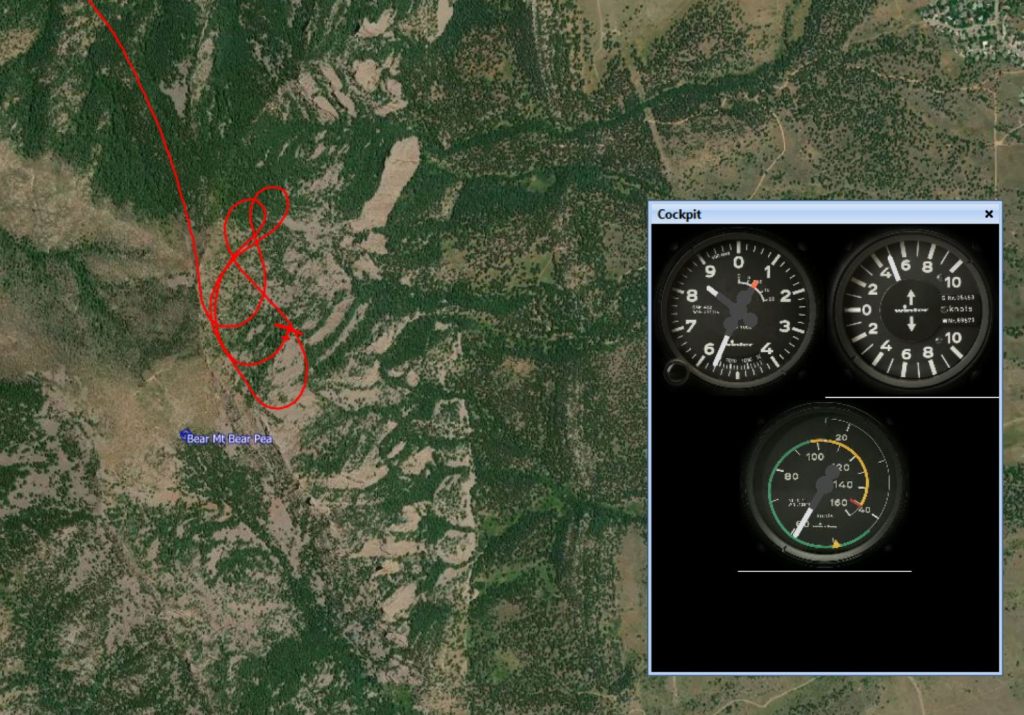

To find the answer I closely compared the early stage of CX’s flight path and of my own flight path to find out where CX was able to connect with the line, and why I missed it. CX’s flight trace is shown in light blue, and my flight trace, SG, is shown in red.

The following screenshots from SeeYou tell and illustrate the story.

After this I continued my flight for a while thermaling over the lower foothills west of the Boulder airport. The thermals were wind-blown and inconsistent and didn’t reach higher than about 8,700 MSL where they were stopped by the wind shear layer between the lower easterly flow and the rapidly moving westerly wind aloft.

So what did I do wrong?

1- I underestimated from the outset how hard it would be to reach the convergence. In particular I did not appreciate that the strong westerly winds aloft would cap the thermal height such that I would not be able to gain the necessary altitude to head west.

2- Because of #1 I also did not have a clear plan for where to tow or how high. On tow I was flying in considerable sink as we approached the 15km ring. Had I released inside the ring, I would have released in strong sink. So I stayed on beyond the sink and released at the first sign of weak lift. That was a mistake because I was just a little too low to comfortably head straight west to get to the convergence. Had I continued on to about 12,000 feet, it would have most likely been sufficient.

3 – I might have had one chance to get far enough west. This was after my first climb off tow when I made it to 10,600 MSL 1 and one mile east of Gold Lake. Had I tried to push another mile west from there it might have just worked and I would have had just enough altitude to do it. Instead, I flew south from there, and at that point my chances to connect without taking undue risks were probably already over.

Here are links to my flight track and to CX’s flight track.

Lessons Learned

- A very strong westerly wind aloft and the associated wind-shear is likely to cap the height of the thermals east of the convergence. The low thermal tops can make it impossible to get the necessary altitude to fly far enough west to reach the convergence (depending on the position of the line).

- In conditions like these it is necessary to tow high enough to have the necessary altitude to fly west and connect with the convergence before running out of safety margin and having to turn back east. (Per launch you might have only one chance to get the line and very little time to connect (perhaps even less than a minute). Seize it when you see it. A few hundred feet of altitude can make all the difference.)

- On OLC Speed League days in these type of conditions (when you can’t get high enough in thermals to penetrate west) there are two alternative strategies to connect with the convergence line and get a valid OLC start: 1) tow to about 12,000-13,000 just at the edge (but inside) of the 15km ring, release, and then head west; or 2) tow further west until you’re confident that you can reach the convergence, connect and gain enough altitude to come back out and dip into the 15km ring, and head back west (and connect again). It is important to consider these alternatives before takeoff and communicate with the tow pilot accordingly.

Post Scriptum

I received several comments via email about this post. Thanks to everyone who read it and took the time to reply. Most comments were about SG’s lack of an engine compared to CX. Here are a few excerpts about what commentators said.

“Big difference you don’t have an engine!”

“Never compare or try to fly with a motor glider!”

“Sometimes it is better to be safe and soar again another day. (The Discus doesn’t have a motor if you get in trouble.) I wonder how that affects personal minimums?”

“If there was sink all the way to just east of Gold Lake I think I would have difficulty deciding to push much toward the divide when off tow. I guess after thinking about it from the back seat, in sink conditions I think I ‘d want to get into some substantial lift before getting off back there.”

Again, thank you for your comments! Here’s what I would say in response:

- In my opinion, the engine factor should not make a difference in a pilot’s judgement (after all you cannot rely on the engine starting when you need it and there are many examples when it doesn’t) but (the limited) empirical evidence suggest that it does influence a pilot’s behavior: a study of all gliding accidents in France over a period of three years showed that the fatality rate in motor glider accidents was almost 3 times higher than the fatality rate in pure glider accidents. The data set is small but it would suggest that pilots of motor gliders are more likely to take higher risks (e.g. fly low over unlandable terrain) assuming that the engine can bail them out if necessary. But when the engine does not start when really needed, an accident is often inevitable and more likely fatal. (BTW – if this is true, it is a classic examples of risk compensation theory – i.e. individuals tend to assume riskier behavior if you add a safety device; frequently cited examples are that motorists drive faster when driving a car with anti-lock brakes; bicyclists cycle faster when wearing a helmet; and skydivers take more risks as their equipment gets safer.)

- I do not think that I should have pushed further west to connect from the altitude that I was at. I think I had an adequate safety margin where I was but my instincts told me not to push any further west and I firmly believe I made the right decision. I do not want to encourage myself or anyone else to take on undue risks.

- I cannot speak for CX but here are a few considerations: In addition to having an engine, CX is a higher performance glider with flaps that enable higher speed penetration through sink, and, most important, the pilot is a lot more experienced than I am. In addition, CX found lift right next to Caribou Ranch, one of the few landable fields in the foothills. (For me it’s just an emergency field, i.e. I would never rely on it, but a much more experienced pilot will probably have no problem landing there.)

- In hindsight, my main mistake on the flight was releasing too early and at the first sign of lift which turned out to be too inconsistent and narrow to climb in. While this decision did not put me in any danger whatsoever (I believe I always had plenty of altitude to come back safely), it ultimately did prevent me from pushing far enough west to reach the convergence line.

- For the avoidance of doubt, I do not at all regret that I did not push further west with the altitude that was available to me. And I most certainly do not want to encourage anyone (myself or others) to take more risk!

Great write up, as usual. Thank you!

It would be interesting to know if Bob’s decision to proceed over Barker was at least partly due to knowing he could restart the engine if he didn’t connect and start over. Not an option in SG.

Great analysis, thanks!