On May, 17, 2022, I became the sixth pilot to finish the Colorado Fourteener Challenge, which has been open to any soaring pilot since 2008. It took me four years and one day to get it done. The completion of this career goal is my most significant soaring achievement so far. But before I tell my own story, let’s first look at what it entails.

The Fourteener Challenge

The highest peaks of the Rocky Mountains have long captivated all types of adventurers. Intrepid explorers seeking to challenge themselves against the forces of nature. Individualists relishing solitude and self-reliance. And romantics questing for places of spectacular beauty.

The tallest peaks of the Rocky Mountains are all in Colorado. More than 50 of them are higher than 14,000 ft, making Colorado the state with the greatest number of “Fourteeners” in the United States. In 1923, Carl Blaurock and Bill Ervin became the first humans to summit all of them. Since then, some 2000 determined individuals have recorded their completion of this monumental achievement with the Colorado Mountain Club. Each year, approx. 50-75 climbers add their names to the list.

In 2008, inspired by this mountaineering challenge, soaring pilots Colin Barry and Doug Weibel, then-president of the Soaring Society of Boulder, had the idea to adapt it for soaring. “The concept was simple”, says Colin, “soar above each peak within a .25 sm radius of the summit.” The coordinates of each peak were gathered, and the list published on the World Wide Turnpoint Exchange. The Fourteener Challenge was born. “GPS navigation and data loggers were becoming ubiquitous, so not only could pilots locate each peak, but we could also validate their progress.”

Hostile Terrain, Capricious Weather, No Place To Land

The challenge is character building. The Rocky Mountains are comprised of a discontinuous series of mountain ranges with distinct geological origins. In Colorado, the orientation of the major ranges tends to be from north to south (e.g., the Front Range, the Sawatch Range, the Mosquito Range, and the Sangre de Cristo Range), but there are exceptions. Some of the mountain ranges, most notably the San Juan Mountains, are so big and wide that a specific orientation is barely recognizable. Between the mountain ranges are the high plateaus of South Park, Middle Park, and North Park, as well as deep valleys. Some of them can be too wide to cross; some are too narrow to land. For newcomers to Colorado, and perhaps even for some Coloradans, the topography can be confounding.

Complex Geography

It took me a few soaring seasons and a lot of map research and Condor flying before I developed a reliable mental picture of the entire state.

The Fourteener Challenge is so demanding because the peaks are sprinkled across multiple mountain ranges throughout the entire state. The distance between the northernmost Fourteener, Longs Peak, and its southernmost counterpart, Culebra Peak, is 217 miles (350 km). The distance between El Diente to the west, and Pikes Peak to the east, is 175 miles (282 km).

Distinct Weather Systems

The mountain ranges are not just hurdles to cross on your way to the next Fourteener; they also tend to divide the state into different airmasses and weather systems. While soaring is often fantastic in some parts of the state, it can be impossible elsewhere. One sector may quickly overdevelop while the air in other sectors may be so stable that soaring is impossible. Winds, cloud bases, moisture levels, thermal strength, thunderstorm propensity, etc. often vary substantially. On some days you can only soar over the high ground while the valleys remain inverted. On other days you can fly over the plains while huge thunderstorms develop over the mountains. Powerful convergence lines may enable exceptional speeds if you follow them exactly; but try to deviate and the air can be as still as at sunrise. Wave aloft sometimes determines where thermals can and cannot form. Storm systems and rotors can cause 20 kt of lift but also 30 kt of sink. Days that work well across the entire state are rare. In-depth flight preparation is critical.

You Must Know Your Turf

As important as understanding the weather is knowing where one can safely put the glider down. Vast areas of the state are unlandable except for airports; and those can be more than 60 miles apart. To make things worse, airports can’t be taken for granted, either. Runways can be quite narrow; tall sagebrush may grow right up to their edges, making some airports completely useless if you’re flying a wide-wing-span glider.

Wildfires can throw another wrench into the best laid plans. They can pop up pretty much at any time of the year. Not only do they cause firefighting TFRs; dense smoke from fires as far away as California can impact thermal development, diminish visibility, and even bring about IFR conditions.

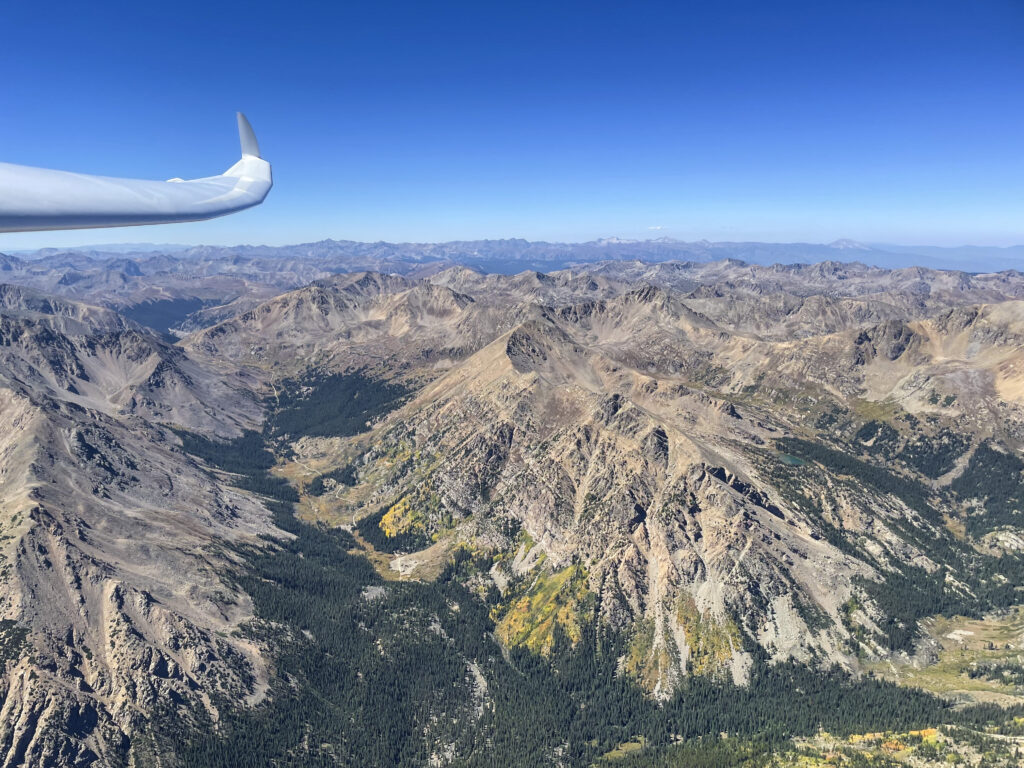

However, as harsh and as forbidding as the Rocky Mountains may be, their beauty is manifest in all directions. In the dry mountain air, the visibility is often 100 miles or more. At 17,500 feet, all of Colorado is spread out below.

For most of us, soaring is not just a science; it is also an art form. We don’t just fly because it is a technical challenge, we fly because there is no better way to see and experience the world. The more difficult the terrain, the more evident its allure. Nowhere is this more palpable than in Colorado.

A Career Goal

For most pilots, the 14er Challenge is best viewed as a long-term career objective. This is particularly true for pilots living in Colorado. Prominent peaks have always attracted glider pilots like magnets and most glider ports in the state have at least one Fourteeners within glide range. Thus, pilots may be able to conquer their first Fourteener within their first or second soaring season. And once a pilot has had a first taste of Colorado Mountain High, they often wonder what else is possible.

For Boulder and Owl Canyon pilots their first 14er is usually Longs Peak. From Boulder, it can be reached in glide range even with the club’s ASK 21 trainer or with a rental glider from Mile High Gliding. For Black Forest pilots the closest 14er is Pikes Peak, also within glide on a good soaring day.

After that, the challenge quickly gets harder. In fact, it involves all the steps of becoming an expert in cross-country mountain soaring: reading the sky; observing the wind; recognizing lift lines and avoiding sink; working the ridges, judging the glide across mountain passes; assessing the odds of finding lift ahead; climbing even in the most broken of thermals; learning to fly farther and faster; and always knowing your turf. It is a journey that cannot and must not be rushed. Ignorance, even one major mistake, can lead to disaster. Pilots must acquire a strong theoretical understanding and accumulate sufficient practical experience to apply it correctly. There are no shortcuts. A steady progression is the way to go.

This will also provide the experience needed to become mentally conditioned for long and strenuous days in the cockpit. “When you’re doing these flights, you’re a long way from home,” says Tom Zoellner, one of the first pilots to complete the 14er Challenge. “The solitary confinement in the cockpit can be overwhelming.”

For those who persevere, the achievement of such a career objective can be very rewarding. For Colin Barry it’s “flying to beautiful remote places,” and the “thrill of planning and completing each mission.” For my part, I think the reward comes from knowing that success is never certain. It’s not easy to put yourself in the right place at the right time, and it may be months or even years until the next opportunity presents itself. This is never more palpable than on a flight when the targeted peak is right in front of you but getting there may put you in a situation where you might have to land out a full day’s drive away from home. Will you give up or will you give it a go? For those who persevere, time and time again, the sense of accomplishment is very gratifying.

Current Trophy Holders

Bob Faris, aka CX, surprised Colin and Doug, the initiators of the Challenge, by completing the challenge on Sep 24, 2008 within its first season. Bob is the chief flight instructor at the Soaring Society of Boulder and holds dozens of state soaring records in Colorado and other states. He owned an LS3 at the time and flew his 14er flights from Boulder (KBDU), Salida (KANK), and Val Air (CD82). Bob considers the San Juan peaks around Silverton the most difficult to achieve. “You have to stay really high there because there are just very few places to land.”

Alfonso Ossorio, aka AO, finished the challenge on Sep 4, 2010 with his most memorable flight – an out and return from Boulder to San Luis Peak in the San Juan Mountains. Like Bob, Alfonso has many thousand hours in gliders. He flew all his 14ers in a Nimbus 2 but rounded many of them also in the club’s DG 505. Alfonso considers the San Juan peaks around Telluride the hardest ones. He reached them on a blue day from the now defunct Val Air airport north of Durango. Al’s advice to prospective pilots is to acquire deep mountain flying knowledge and to always pay attention to the wind. “Watch it, read it, use it.” He recommends Helmut Reichmann’s book ‘Cross-Country Soaring’. And most of all, “to have fun!”

Tom Zoellner, aka XR, became the third pilot to finish the challenge on June 5, 2018. Of all the finishes do date, Tom’s is the most remarkable achievement. Not only did he fly all his flights in an ASW20 without water ballast. He is the only one to achieve the entire challenge from Boulder! Reaching the farthest peaks in the San Juan’s required flights of more than 8 hours and 850 km across all the major Colorado mountain ranges while also tagging some of the most difficult turn points imaginable. Tom comes from the rock-climbing world and finds many analogies. “Like in climbing, skills are relatively easy to acquire. You can learn how to thermal; you can learn how to fly fast.” “But skills will only get you so far. This goes way beyond skills. You might be out there all alone and needing to land out.” “Do you know how you perform under severe stress?” “Ultimately, it is how you feel and your belief system that will give you the greatest success.”

Colin Barry, aka Yankee, the father of the 14er Challenge, finished his own quest on August 30, 2019 in his Discus 2 after starting as early as 2002. 17 years later he still had the most difficult San Juan peaks left to go when he travelled to Salida to get it done. “My last flight to bag the remaining peaks was the hardest,” says Colin. “I had planned it for years. On the day I thought the weather was going to make it impossible, but a cloud street guided my way.” “This is the most isolated place in the Continental United States,” he adds. “Man, it’s high and remote out there!” “But I had put a lot of time into planning safe landing places, and I was fairly relaxed because of that.”

Benjamin Pinnell, aka FE, became the second pilot to complete the entire challenge within a single season. In 2021, he bought a roof-top tent for his SUV and decided to devote the soaring season largely to the Fourteener Challenge. In addition to flying from Boulder, he travelled to Salida and North Fork Valley to get it done. Flying his DG400, he started on April 3 bagging Torreys and Grays on the Front Range. On August 17, only 5½ months later, he completed the challenge with a flight to Culebra Peak, the southernmost Fourteener in the Sangre de Cristo Range. Upon receiving his award, Ben kindly offered to sponsor the next five trophies so the challenge could stay alive.

Clemens Ceipek, aka V1, i.e. yours truly, became the sixth finisher on May 17, 2022. My own 14er journey is detailed below. A list of all 14ers with links to my flight traces for each can be found here.

My 14er Journey

Summits Within Glide Range: The Northern Front Range

I began my 14er quest at the start of my second soaring season at Boulder. On May 16 of 2018 I recorded a 447 km flight during which I bagged Longs Peak, Grays Peak, and Torreys Peak, flying a club Discus CS. At that time, I had a total experience of about 150 hours, and this was my longest flight to date.

A week later I added the remaining 14ers on the Northern Front Range: Mt. Evans and Mt. Bierstadt. In a 40:1 glider, each of these five peaks can be reached within glide range from Boulder if one is able to stay above 17,000 ft.

Going Cross Country: Pikes Peak

Shortly thereafter came my first big jump. Bagging any other 14er from Boulder necessitates a true cross-country flight, i.e., leaving glide range from the home airport. Pikes Peak, 83 miles south of Boulder, also known as “America’s Mountain,” was a compelling attraction. There are long stretches without any airport to cross and a lot of complex and unlandable terrain to fly over.

I was prepared. I had extensively researched land out fields over the winter. And I also visited many of them on the ground. In addition, I studied maps and terrain obstacles to determine how high I would need to be in all parts of my task area to safely reach the nearest landable field at a glide ratio of 21:1, half of the Discus’ best L/D. When the right day came, I felt ready. The forecast supported flying a triangle by first crossing South Park towards Buena Vista and then bagging Pikes Peak before heading back home. It worked; but taking the leap beyond glide range still required summoning all my courage.

Here’s the flight trace and my writeup of this flight at the time.

Getting Comfortable with South Park: Tenmile Range and Mosquito Range

At an elevation of approx. 10,000 ft, South Park is a large high plateau flanked by the Kenosha and Terryall Mountains to the east, the 39-Mile Volcanic Field to the South, the Mosquito Range to the west, and the Continental Divide to the north. Five of Colorado’s Fourteeners are in the Mosquito Range and one, Quandary Peak, is just a little further north in the Tenmile Range.

To reach these six Fourteeners from Boulder I had to traverse the north side of South Park. Often, a convergence line sets up where the prevailing westerly winds at altitude meet the anabatic flow near the surface towards the Continental Divide. When it works, it can be a formidable highway in the sky towards the Mosquito Range and sometimes beyond.

On other days, South Park can be tricky. There are no public airports anywhere. Two of the three private airstrips, Lux and Antelope, are usually landable – except when they are not because a herd of buffalo or elk roams the runway just when you need it. (A third is too narrow for gliders).

But the area is largely flat and there are many hayfields that can be used to land – unless the hay happens to be too high, the field happens to be flooded, or you run into rocks or an irrigation ditch. At any rate, knowing where you can land is key.

This knowledge came quite handy on my flight on July 19, 2018. The convergence had worked until Fairplay but getting onto the Mosquito Range was very difficult. I spent a long-time ridge soaring the north side of Mt. Silverheels in a northwesterly wind, delaying what I thought would become an inevitable landout. But ultimately, I was able to climb back up to altitude and jump onto the ridges between South Park and Leadville where I got my Fourteeners. Four years later this flight is still firmly lodged in my memory as one of the more difficult challenges. Here’s the flight trace and a writeup.

Stretching Out Further: Sawatch Range, Elk Mountains, and Northern Sangre de Cristo Range

More than two years would pass before I was able to add new peaks to my list. It’s not that I didn’t fly in 2019. I just chased different goals, most notably Diamond Distance. One takeaway from my flight into the Mosquito Range had been that 14er summits don’t make the best turn points when you try to fly long pre-declared tasks: they can be nearly impossible to reach!

And one more thing had changed in 2020. At the start of the year, I bought my own glider, a Ventus 2cxT. With flaps and 18m wings it could go substantially further than the club Discuses. Having my own ship also meant that I could reliably fly on the best days of the year. After completing my 750 Diplome (which took me eight attempts over the course of the summer), I shifted my focus back to the 14ers.

The Sawatch Range and the Elk Mountains

The beginning of September brought dryer weather after a wet monsoon season. This meant high cloud bases, no overdevelopment, and no thunderstorms: ideal conditions to go after the tallest peaks. On back-to-back days, September 4 and 5, I flew two awe inspiring flights bagging 14 of the 15 Fourteeners in the Sawatch Range (flight trace, in-flight video) and all 7 in the Elk Mountains around Aspen (flight trace, in-flight video).

If your normal reference point is driving, these mountains are much closer than you’d think. By car, it takes almost 4 hours to get from Boulder to Aspen; in a glider, it can be done in a little over an hour when the conditions are right!

It is awesome to look down on Castle Peak, South and North Maroon Peak, Capitol Peak, Pyramid Peak, Conundrum Peak, and Snowmass Mountain. The scenery is simply spectacular! And the Sawatch Range with its Collegiate Peaks is no less impressive. And of course, there’s Mt Elbert, the tallest summit in all the Rocky Mountains and the second highest peak in the contiguous United States, just 65 feet lower than Mount Whitney in California.

As far as the challenge is concerned, both flights were surprisingly easy. If conditions are right, these peaks can certainly be bagged in a Discus as well.

Mount of the Holy Cross – A Challenge In Itself

That left the northernmost peak in the Sawatch Range: Mount of the Holy Cross. I consider it the hardest peak in these mountains mainly because the landing options are particularly dire.

To get there from Boulder you must first cross the Blue River Valley where there is no place to land south of Dillon Reservoir – unless you want to make yourself the attraction of the Breckenridge Golf Club. From there you head over Vail Pass and the inhospitable upper Eagle River Valley. Here you must stay high enough to always be able to reach some small fields near the town of Edwards. On Sep 13, conditions were right for this adventure. After a difficult climb-out from Boulder near the Continental Divide I had an uncomplicated run to the summit and back. The first snow of the season had fallen in the mountains just days before and the views were extraordinary. (Flight trace.)

Northern Sangre de Cristo Mountains

The following day, Sep 14, was even better. My goal was to start collecting peaks in the Northern Sangre de Cristo Mountains. And I had company! Bob Caldwell, aka BC, one of Boulder’s most experienced XC pilots, joined me on a team flight. This turned out to be of great help as I had never been so far south. I also wasn’t familiar with some of the intricacies of the weather systems impacting the Sangres.

We took a westerly route across the Mosquito Range to the Sawatch Range, then crossed to the Sangres at Poncha Pass. I started to head south along the western edge of the clouds which had been working before. However, I only found sink. Fortunately, BC pointed out just in time that the wind had changed to an easterly direction. The clouds along the Sangres were the result of a convergence between an easterly flow spilling over the spine and a moister, more stable, airmass sitting over the San Luis Valley. That meant the lift was on the east side of the clouds despite the sun being to the west. Once I realized what was going on, flying became easy again. I was able to head south bagging Crestone Peak, Crestone Needle, Kit Carson, and Humboldt Peak.

Here’s the flight trace and a detailed in-flight video of this amazing team flight with BC.

The Hardest for Last: Southern Sangre de Cristo Range and San Juan Mountains

At the end of 2020, I was still missing the five southernmost peaks in the Sangre de Cristo Range and all the Fourteeners in the San Juan Mountains. Much of my spring and summer soaring was devoted to glider racing in other parts of the country. I decided I would refocus on the 14ers during a club soaring camp in Salida in the fall.

Blanca Massif

Sep 13, 2021, was my first day flying from Salida. It was very windy. I quickly got washed out trying to head towards the San Juans and decided to head south along the Sangres. I had imagined that I could make quick progress in ridge lift but found that the terrain isn’t all that suited for ridge running. There simply isn’t one continuous ridge line to fly along. Instead, the wind is channeled and diverted along the many spurs that protrude from the main spine in the center. However, I found rough thermals above the spurs and the more wind-protected bowls that were good enough to proceed.

Heading towards the Blanca Massif the clouds thinned out. But I had come too far to give up. In the worst case, I would land at Trichera, a big private airstrip south of Blanca Peak built for a private jet, from where I could call the tow plane to get back to Salida. Fortunately, that wasn’t required. I managed to bag the four Fourteeners in the Blanca Massif. From there I tentatively sought to fly south towards Culebra Peak in the Southern Sangres. However, hitting strong sink in the lee of the mountains, I didn’t get very far. Prudently, I decided to wait for a better day to tackle the last remaining 14er of the Sangres. Here’s the flight trace.

San Juans – Part 1

The next day, Sep 14, looked much better for going west towards the San Juans. My plan was to fly around the rim of the entire mountain range, bagging as many of its 14 Fourteeners as possible. The day was incredibly dynamic.

Unfortunately, the central and southern part of the mountains overdeveloped very quickly, which confined my flight to the northern edge of the range. But I still bagged four Fourteeners: San Luis Peak, Uncompahgre Peak, Wetterhorn Peak, and Mt. Sneffels.

The fall colors were at their peak and the yellow aspen glistened in the sun against the backdrop of dark clouds, virga, and rain showers. Of all my 14er flights, this was hands-down the most beautiful. The flight trace is here.

On the following days the weather did not support distant excursions. This left the hardest 11 Fourteeners for another season: Culebra Peak, the southernmost peak in the Sangre de Cristo Range, as well as the central, southern, and westernmost peaks of the San Juan Mountains.

Culebra Peak – The Southernmost Fourteener

I thought the next opportunity would arise at the subsequent Salida camp in May of 2022. However, another window opened just two days before the camp when conditions to the south looked exceptionally promising. On May 15, I declared a border-to-border flight from Boulder that I hoped might take me to New Mexico, Wyoming, and back home. If all went well, I would collect Culebra Peak along the way.

I launched early but struggled mightily in rotor lift under a low cloud base until I was south of Highway 285 where conditions improved. Transitioning from the Wet Mountains to the Sangres represented the next big hurdle. I lost 4,500 ft and dropped to 12,500 ft before finding lift at the base of the Blanca Massif where I had to work hard to resist the urge to give up. Most convincing was the fact that I didn’t want to make the same transition again… Maybe things would improve while I pressed on.

The Southern Sangres worked splendidly. At 3pm I reached Culebra Peak and eight minutes later I was at the New Mexico border. No time to relax though – I had a long way to make it back home. I made good time on the return, averaging more than 100 miles per hour. However, once I was back on the Northern Front Range it quickly became obvious that the day would end early. The border-to-border goal would have to wait for another time. But Culebra was in the bag! The trace is here.

San Juans – Part 2

The following day I drove to Salida where I would take off early on May 17 in pursuit of my remaining 14ers in the San Juans. I could not have wished for a better day. The thermals were strong, the clouds plentiful, and the westerly winds light to moderate. The only concern was overdevelopment and virga.

The trick was to start early. Which was not a problem: the first clouds popped at 10 am with bases that were already at or near 19,000 feet. Cloud bases would later rise to about 23,000 ft! I launched at 10:40am, climbed to 17,500 ft right next to the airfield and was on course by 11am. Just an hour later I had covered 85 miles and rounded my first set of 14ers in the central San Juans: Redcloud Peak, Handies Peak, and Sunshine Peak.

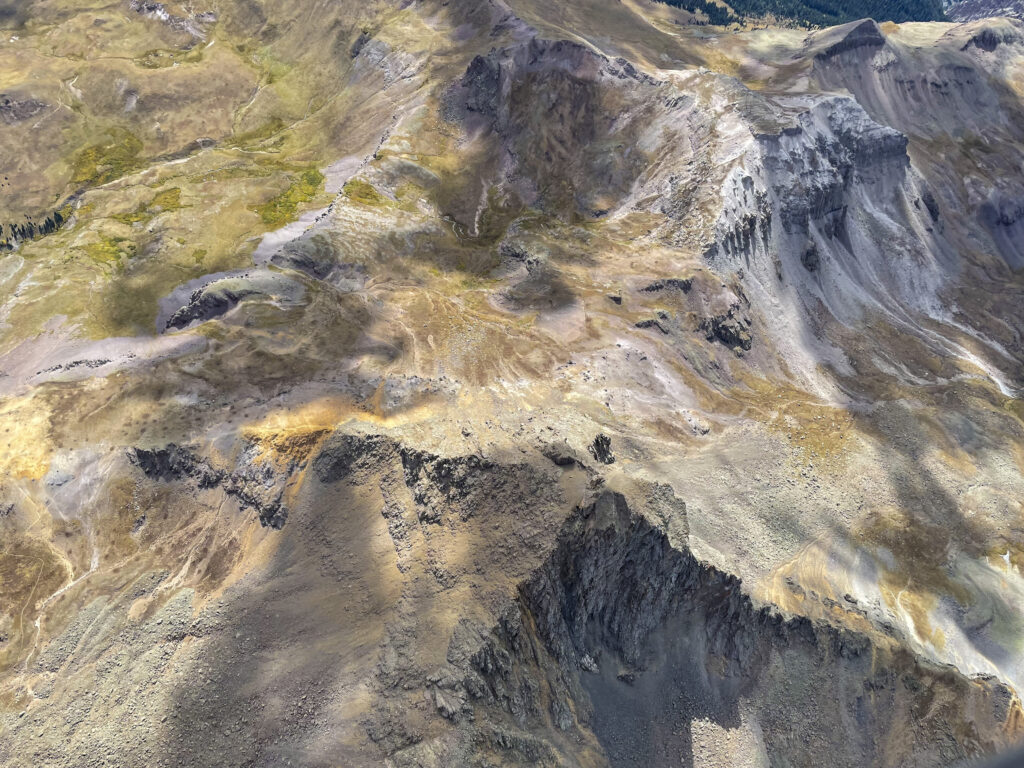

From there came the dreaded 25-mile transition to the southern edge of the San Juans. This is the wildest and most forbidding area in Colorado. The terrain below consists of a sea of high mountain peaks, all about 13,000 feet or higher. The steep and narrow valleys are completely unlandable, and the most accessible airport is between 40 and 60 miles away. There were also some gaps in the clouds in this area. By taking every weak climb I could find I managed to stay high and always kept an out – first to the north, then to the south. Good clouds in either direction gave me confidence that even if I had to take an escape route, I would be able to climb back up. This was the slowest part of the flight. However, I stayed safe, and by 12:30 pm I bagged Windom Peak, Sunlight Peak, and Mt Eolus (as well as North Eolus). That left the three westernmost peaks to go. Fortunately, there were nice clouds along the way too, and 20 minutes later I had rounded them all: El Diente Peak, Mt. Wilson, and finally, Wilson Peak.

Four years and one day (and ~700 glider hours) after I had made it to the top of Longs Peak the Fourteener Challenge was complete!

Practical Information for Aspiring Contenders

The 14er Challenge is open to any soaring pilot. The rules can be found on the homepage of the Soaring Society of Boulder. The Challenge is currently hosted and administered by Benjamin Pinnell at the Soaring Society of Boulder.

Qualifying flights can be flown from any airport. However, Tom Zoellner has demonstrated that the challenge can be accomplished from one single airport (Boulder, KBDU) – a substantially more difficult achievement.

The most centrally located airport for all the 14ers is Salida (KANK). It’s the best choice for visiting motor-glider owners but there are no permanent tow operations and visitors have to bring their own oxygen. Salida is a great mountain town with excellent restaurants and many activities for families. Afternoon winds can be ferocious at times, but the soaring is amazing!

For those without self-launching gliders, Colorado has several airfields with regular tow operations:

-

- Boulder (KBDU) – home of the Soaring Society of Boulder (the biggest soaring club in Colorado) and of Mile High Gliding (a long-established commercial glider operation where tows can usually be obtained on any day of the week).

- Owl Canyon (4CO2) – home of the Colorado Soaring Association

- Kelly Airpark (CO15) – home of the Black Forest Soaring Society

- Eagle Soaring (1CD4) – home of the Steamboat Springs Soaring Association (winch operations only)

The best months of the year for the Fourteener Challenge are May through September. Look for days with high cloud bases (18k and above) and light to moderate winds. Beware of afternoon thunderstorms, especially from July through mid-August (monsoon season). Wave conditions (frequent between October and April) are usually not well-suited for the 14ers.

Also watch this excellent presentation by Soaring Society of Boulder pilot Tom Zoellner about his quest to complete the challenge.

Tackling the 14er Challenge requires substantial theoretical and practical experience in mountain soaring as well as diligent preparation (e.g., terrain and landout field research, in-depth weather briefings, retrieve arrangements, etc.). Oxygen is a must!

Congratulations. A remarkable achievement .

( from a Florida pilot – Highest state elevation 320 feet )