August 12 was my second day flying in the Alps this year. The forecast conditions were rather poor, which surprised me because a cold front had passed through the day before, finally putting an end to the oppressive heat wave that had lasted for more than three weeks. Post-frontal weather often offers good soaring in the Austrian Alps.

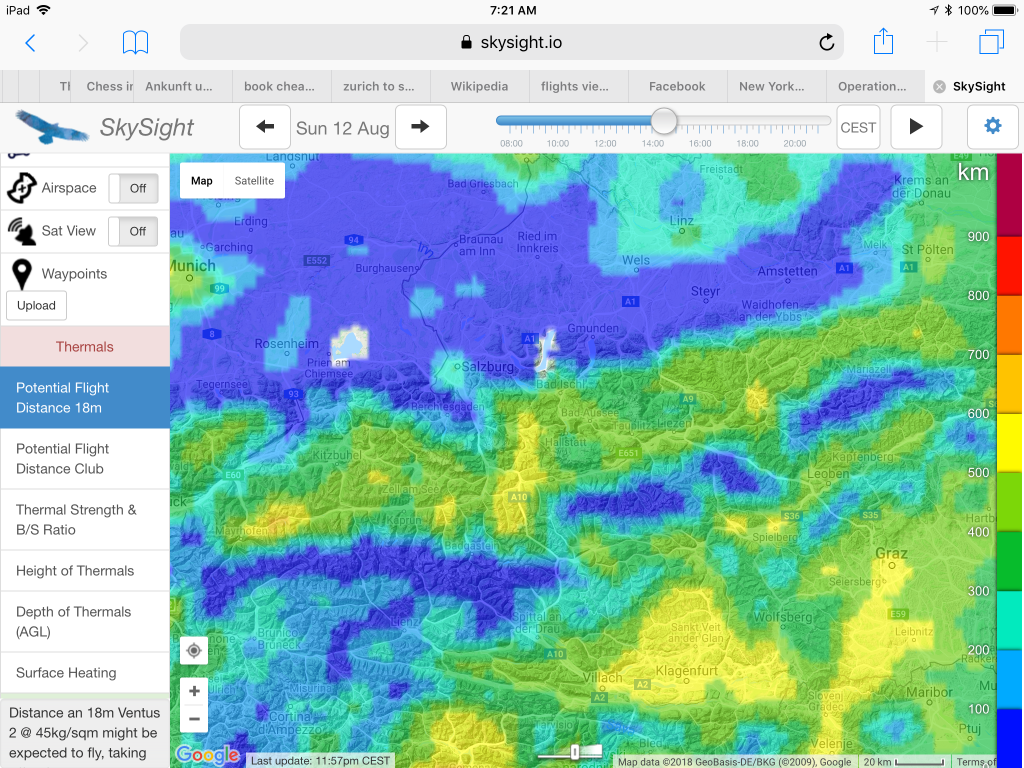

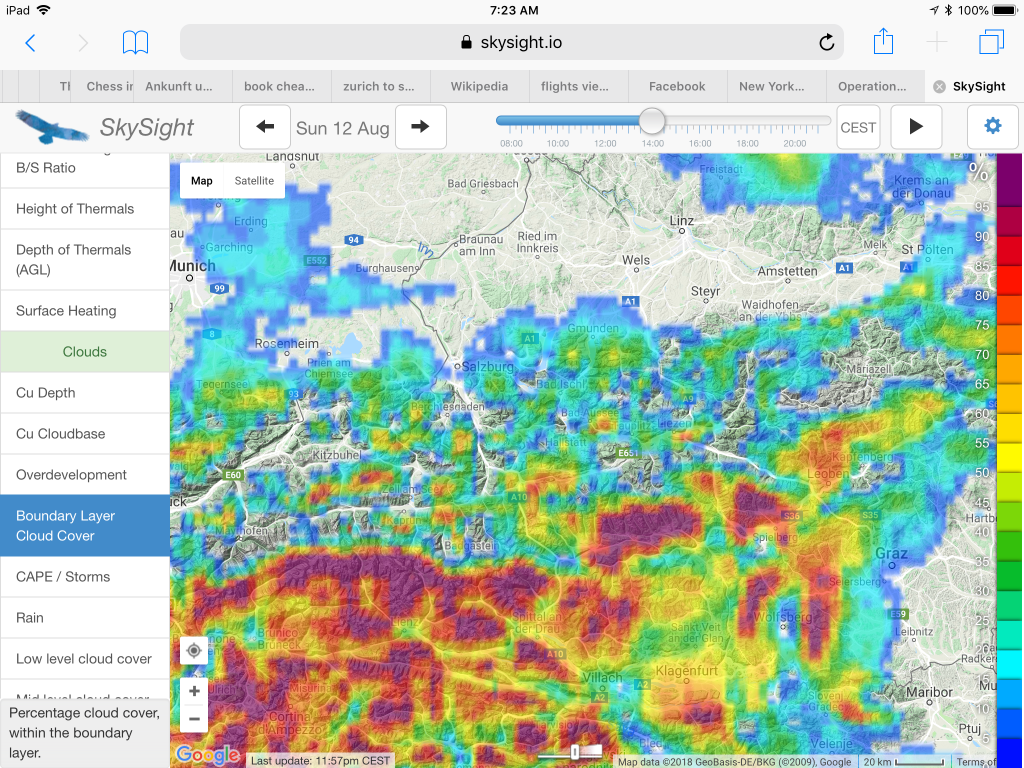

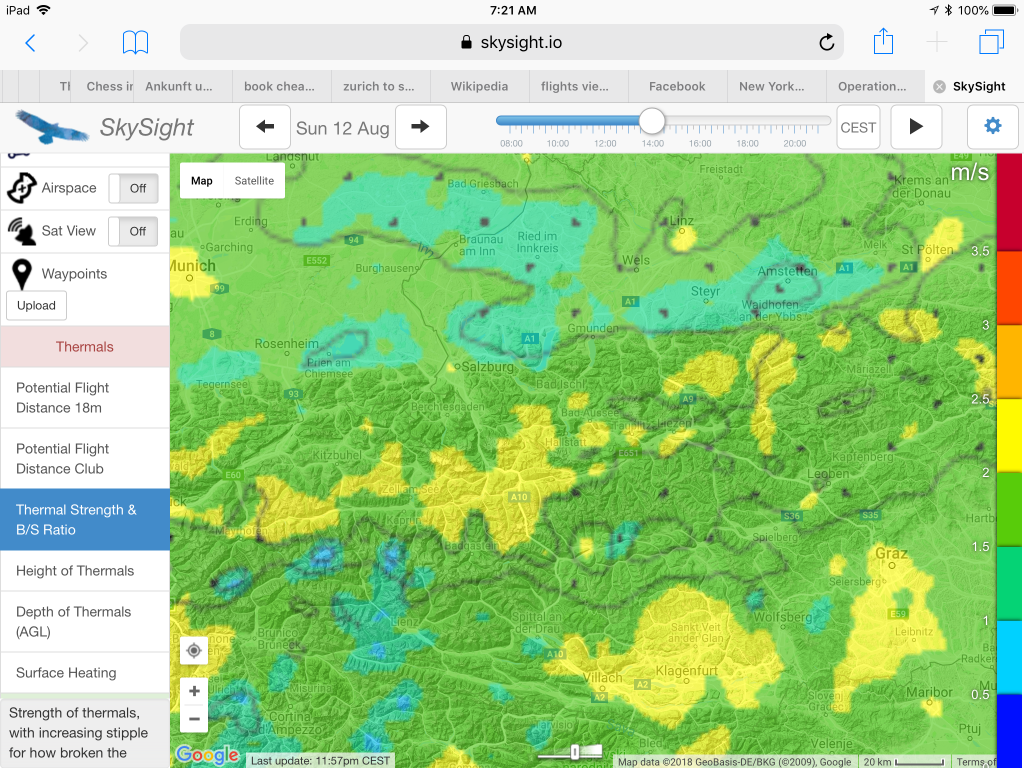

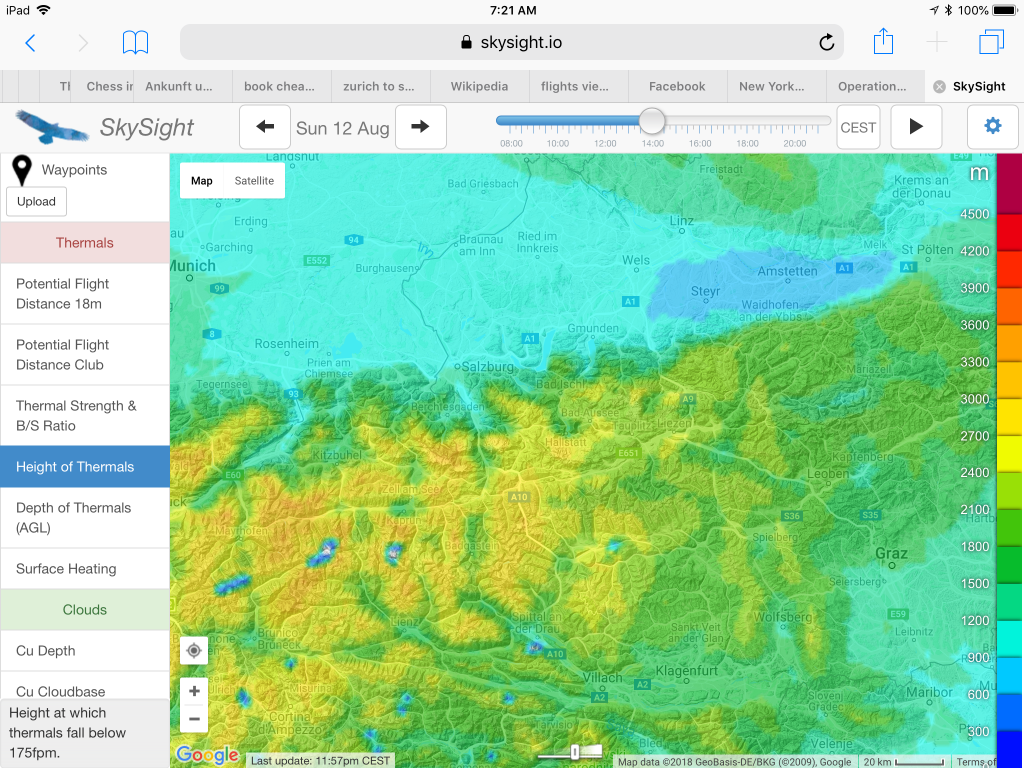

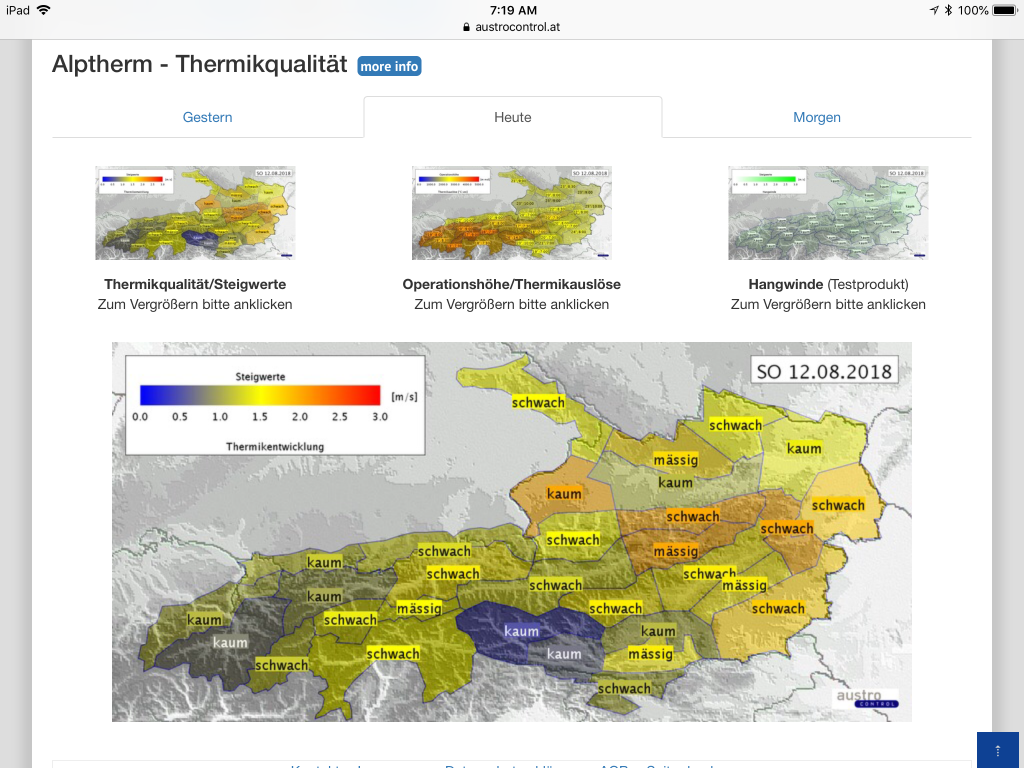

The local forecast from AlpTherm predicted weak (“schwach”) climb rates around 1 meter/second (2kts) with thermals up to 3,000m (10,000 feet). SkySight was more encouraging, indicating a potential flight distance of 400-500km (in an 18m ship) supported by a long soaring day starting as early at 10am, 1.5 – 2 m/s thermals, nice cumulus clouds, no OD, no storms, and no significant high-cloud obstruction. Light southerly winds would contribute to dense clouds stacking up on the south side of the Alps’s main spine, but were likely too weak to be usable for ridge soaring. SkySight projected even lower cloud bases than AlpTherm at the east side of my soaring area – as low as 2,400m (8,000 feet) – yet gradually rising to 3,300m (11,000 feet) further west.

My drive to the airport started at the southern side of the Alps under a layer of dense clouds. As I crossed to the north at Wald am Schoberpass, the clouds gave way to deep blue skies. The air was also much clearer than in recent days: obviously the cold front had removed the inversion layer. A few low-hanging clouds clang to the slopes of the mountains, remnants of the moisture that the heavy rains of the passing cold front had left behind. There was no doubt that the sun would quickly dissolve them.

By 10:30am the first new wisps started to form above the hills, indicating that lift was already starting to form. I moved the glider out onto the grid at Runway 04 while the air on the ground was perfectly still. I was confident that it would not take long for the valley breeze to kick in. At 11:30am the windsock finally came alive – a clear sign that it was time to launch because the thermals above the hills were sucking in air from the valley below.

I was number three on the start list and airborne by 11:44AM. Once again I asked to be towed to the trusted release point near Karlspitz at 1,800m MSL (6,000 feet), around 1,100m (3,300 feet) above the valley floor, where I released in the first lift above the ridge seven minutes later.

Unable to climb from my release point at less than 300 feet above the ridge I thought I might have released a tad too early when a thermal above the nearby hill Zachenschöberl lifted me to cloud base at 2,400m MSL (8,000 feet). My average climb rate was 1.5m/s (3kts) – not bad considering that the day had only just started.

I had set a tentative turn point 126km further west above Pass Thurn. To get there, I would have to first fly along a mountain chain called the “Schladminger Tauern”, followed by the “Radstädter Tauern”, and eventually the Hohe Tauern.

The peaks of the Schladminger Tauern and the Radstädter Tauern top out at about 2,850m (9,500 feet). The ridge lines along the foothills are typically about 1,800 to 2,400m high (6,000 – 8,000 feet). Every 5-8 km or so I would have to cross one of these ridges.

A cloud base of 2,400m did not leave a lot of wiggle room: I would have to climb to cloud base above a ridge line, glide through sink to the next ridge, hopefully arrive there with a decent safety margin, find a climb that would take me back to cloud base, fly through sink to the next ridge, and so forth. To make progress, pretty much every ridge line had to offer a climb and I would have to be able to locate it quickly once I got there. Should a ridge not work upon arrival, I would have to follow it towards the main valley (perpendicular to my intended route) and look for climbs along the way. Should I find myself unable to work my way back up, I would eventually have to land at one of the few land-out fields in the main valley.

Eventually I would get to the “Hohe Tauern”, which were much taller with peaks around 3,600m (12,000 feet). Low hanging clouds, tall mountains, and soaring don’t mix very well; therefore, I planned to cross the Salzach Valley around Zell am See to the north side and then continue along the lower Kitzbühler Alpen, which top out around 2,500m (8,300 feet) until I would get to my turn point. From there I would retrace my route back towards the east, continuing on to a second turn point at Admonterhütte near the town of Admont and then return back to Karlspitz for a total task distance of 325km. That was the plan.

As I headed out on task I observed a seemingly endless line of clouds along the south side of the Alps, just as Skysight had predicted. On the north side, where I was flying, small but pretty cumuli started to form right above almost every ridge line.

My first ridge to cross would be near the peak of Gumpeneck, 2,226m tall. I had hoped to arrive just at the level of the peak, high enough to connect with the thermal breaking off the mountain. However, when I got there I was down at 2,080 meters, just a little too low to get into lift. That meant plan B: follow the ridge out towards the Enns Valley. Only one kilometer later I found weak lift above the ridge, worked my way up to to 2,300m, flew back to the Gumpeneck, and climbed back to cloud base at 2,370m. On to the next ridge!

I arrived 130m AGL (400 feet) above the next ridge and quickly found the next climb, which took me from 2,200 to 2,570m. Great! The cloud bases were getting higher. Onwards!

The next ridge was 2,200m high. I arrived there 300 feet above ground, following along the ridge for about 2 kilometers but did not find a climb. Time for plan B again: change direction, and fly above the next lower ridge line out towards the Enns Valley. 50 meters AGL I found the next climb, taking me from 2,150m back to cloud base at 2,480m. Time to push west again!

The next two ridges were good enough to maintain altitude but provided no climb. I was only 1 kilometer north of a peak that was 2,450m tall – too high. The lift was probably above the peak but I was down at 2,350m and couldn’t get there. So I continued on.

The next ridge was slightly lower at 2,150m. I got there 100m AGL and found a nice climb back to cloud base at 2,580m.

This is how my flight towards Zell am See continued. I found climbs to cloud base above each of the next three ridges, then skipped a ridge and had no choice but to take the next climb back to 2,500m even though the climb rate was dismal. A fun way of soaring but mentally very demanding. And so slow!

Then came the next ridge and finally some reprieve: my first 2 m/s (4kt) climb of the day took me to a new high: I was at almost 2,900m! The airport of Zell am See was now within easy glide range and I could relax a bit. But I was already 90 minutes on task and had only covered just a bit over 50km!

I continued to push on and the flying finally got faster and easier. Climb rates continued to improve and the cloud bases increased further. The additional altitude gave me room to increase my inter-thermal cruise speed from 120 kph to 140 kph. Above Bernkogel I averaged 2.5 m/s and climbed to 3,050m. Oh what luxury!

Finally I had time to look ahead towards TP1. At least in theory there were two ways to get there: 1) continue on the south side of the Salzach Valley and cross to the north side near TP1; or, 2) cross to the north side near Zell am See (as I had initially planned) and then continue along the Kitzbuühler Alpen.

The southern route looked very challenging: the mountains to my left were intimidating: the peaks towered high above my glider and were well above cloud base. The ridge lines ahead were short and provided few options to find good climbs. There was still some wind from the south and I dreaded the prospect of flying in the lee of these monsters. Unfortunately, the northern route did not look very promising either. The sky in that direction was mostly blue and the cloud bases were much lower. Crossing over to the north looked straightforward but would I be successful in crossing back south? I didn’t know.

For a while I contemplated my options. The airport of Zell am See – one of the premier soaring sites in Austria – was right below and provided an easy and safe landing option in case my adventure to the north side did not work out. However, I could not see any other gliders around, which caused some doubt in my mind regarding the conditions on the south side. Also, it had already taken me more than two hours to get here and I didn’t know how long it would take to get back. It was 2:15PM and Skysight had predicted thermal activity to weaken considerably as early as 4PM. Ultimately, the doubtful voices prevailed. I decided to abandon my task and turn around.

In hindsight, my concerns were probably overblown. Conditions continued to improve. I averaged almost 3 m/s on my next climb and reached 3,150m. Finally I was able to skip some ridges if the attainable climb rates did not reach my expectations. My average speed, which had only been 56 kph on my outbound leg, improved to 78 kph on my next leg.

Once I was back within final glide range to my start airport in Niederöblarn I reversed course again to head back west to see if I could further improve my average speed. Indeed: on my second westbound leg that took me back to Zell am See again I averaged 82 kph.

I briefly thought about continuing to TP1 now as the Kitzbühler Alpen looked considerably improved, but it was almost 4PM and prudent caution won again.

I had not anticipated that things would get better still until thermal strength peaked around 4:30PM. On my second eastbound leg I averaged 105kph. I started to wonder if I could even score for the OLC Speed League despite the excruciatingly slow start.

Around 5PM, however, it quickly became obvious that the day was coming to an end. I crossed the Enns Valley, found another climb over the Grimming and added a sightseeing flight along the Northern Limestone Range. I had hoped for a similar late-day “radiation-lift” effect from the steep south-facing cliffs as I had noticed on my prior flight on August 4. However, this time the air along the shaded cliffs just produced sink.

Near Dachstein I crossed the valley again and found the day’s last thermal over Planai Peak, famous for world-cup ski racing. From there I followed the ridge lines, which had become completely still, back to the airport in Niederöblarn for one of my smoothest touch-downs ever in completely calm conditions just before 6PM.

Total flight distance 392km. Average Speed, unsurprisingly slow, at 68.5 kph. The flight track is here.

Lessons Learned

- Flying low is (mentally) demanding. The work load is dramatically higher when you have no choice but to fly low. Having a plan A (where to go for lift), a plan B (where to go if lift does not materialize), and a plan C (where to escape to – if necessary to land – if plan B does not work) is critical. And what your plan A, B, and C ought to be changes constantly. I.e., every few minutes you may need to formulate a new plan A, B, and C. That’s a lot of work.

- Lift above the ridges can be very narrow. I noticed that the lift close to the ridges can sometimes be just a thin band that may be impossible to circle in. If it is wide enough to circle a steep bank angle (40-45 degrees) is often required to stay in lift – also and especially because you can’t afford to get close to minimum speed while in close proximity to the terrain. Two or three times I found myself circling with other gliders who ended up dropping out of the lift because their circles were just to wide.

- Always arrive above the ridges. Hopping from ridge to ridge only works if you can be sure of arriving above the next ridge line, ideally above the highest peak along the ridge for that’s where you will most likely find the next climb. If you’re not 100% certain of that, than your plan B must include a path over another (lower) ridge line that you can reach for sure above the ridge (plan B) and from where you can escape to a landable area (plan C).

- Always watch your airspeed as you approach a ridge. When you are approaching a ridge close to terrain you might intuitively pull back on the stick and inadvertently reduce your airspeed. Never let that happen. Flying close to terrain is dangerous and flying too slow and too close to terrain can be a fatal combination. I kept reminding myself of this throughout the flight.

- The combination of low cloud bases and weak lift makes you SLOW. The obvious part of this is due to the fact that you take a long time to circle in weak lift and that you have to maintain a modest airspeed even in cruise mode. Less obvious are the other delays: i) you have to take (almost) every climb simply because it is still better than plan B. ii) And if plan A does not work you may be forced to significantly detour from your intended flight route simply to find the next climb and stay aloft – as a result you end up flying many more unintended miles along the way and this is what really slows you down.

- Skysight has been remarkably accurate. Always read any forecast with some skepticism and never expect it to be 100% correct in every respect. However, once again Skysight was very close to reality: e.g., by mid-afternoon, climb rates were a little stronger than forecast and cloud bases a little bit higher. The most clouds were almost exactly where Skysight had predicted them to be. The start and end of the soaring day were both perhaps 30-45 minutes later than forecast. The southern side of the Enns Valley worked a bit better than forecast and the north side a little worse. But overall, Skysight was remarkably on target. Having worked with it now in different geographies and widely different conditions I believe it’s the best soaring forecast out there at the moment.