This past Saturday we had another textbook convergence line form above the foothills west of Boulder. Climbing into convergence was quite tricky – as it often is – but there are amazing rewards for those who can make it.

I was able to video tape my flight and since there were outstanding markers that showed exactly where the convergence formed, I thought I would put together some in-depth explanations for how to get there and how to follow the lift line once you’ve made it.

You can find all of that in the following video:

In addition, I have tried to summarize 10 key lessons for flying in Rocky Mountain convergence lift from Boulder.

(1) Find a good climb after releasing from tow and climb as high as you can.

If your first climb takes you to 14,000 feet you are probably already set and can head straight to the convergence. However, on most convergence days, the thermals east of the convergence line will top out at much lower altitudes. Above the lower foothills it is common that the lift will only extend to about 1,000 – 3,000 ft AGL. It is therefore very common that your first climb may only take you to 8,000 or 9,000 ft MSL.

On Saturday there was no ground inversion and I was able to release in good lift right above the airport and climb up to cloud base, which was at 10,000 feet MSL.

Note: when there is a ground inversion over the plains there might not be any lift near the airport. If that’s the case you probably need to take a mountain tow to get into the first good thermal that can take you to cloud base.

(2) Once you’re at cloud base, head west towards the hills and look for lift that can take you a bit higher.

The goal is to get high enough to reach the convergence line. How high you have to get depends on where the line is located and, therefore, what altitude you need to get there safely and be able to return to Boulder should you be unable to connect with lift.

If the lift tops out relatively low to the ground (at about 2,000 ft AGL or even lower) you will likely need multiple climbs as you head west. Each climb is likely to take you a few hundred feet higher, commensurate with the increase in altitude of the terrain below. E.g. 2,000 feet above Nugget Ridge will take you to 9,200 ft. The same altitude AGL above Gold Lake will take you to 10,600 ft.

The convergence line might be as far east as the first hogback or it might be as far west as the Continental Divide itself. The altitude needed to reach it safely obviously differs greatly based on how far west the line is located. Most of the time, the line is within a few miles (east or west) of the Peak-to-Peak Highway.

Weather forecasts can help you determine where the line is likely to be. E.g., Skysight has a dedicated page for Convergence and will predict the location of the convergence line throughout the day in 30 minute intervals. You can get essentially the same information by looking at vertical velocity on the RASP forecast. Note, however, that the position of the convergence is notoriously difficult to predict so expect the forecast to be off by several miles.

On Saturday, I found a climb over the foothills to the northwest of Gross Reservoir under a cumulus cloud that took me to cloud base at about 11,000 ft MSL.

(3) Look for markers that indicate where the convergence line is likely to be.

The convergence may or may not be marked. Blue days are difficult because the line can be very hard to find and following it is also very challenging. If there are no clouds at all, all you may have to go by is the “feel of the air.”

More often than not, there are at least some cloud indicators that show the position of the line. However, they are not always as easy to spot as this past Saturday.

This is what the sky looked like when I left my climb at Gross Reservoir at 11,000 ft MSL and continued to head west towards Nederland (at the right edge of the picture).

- Overhead on the left of the picture are remnants of the cumulus cloud that marked the thermal I just left.

- Left of the nose (towards Thorodin Mountain) are additional thermal-marking cumulus clouds, which have a similar base as the cloud that I’m just leaving.

- But the most interesting clouds are the scraggly-looking clouds further west. In addition to their different shape and appearance you can also notice that the base of these clouds is considerably higher. They are not ordinary cumulus clouds but are “curtain clouds” marking the location of the convergence.

Confronted with the situation shown in the picture above, it is evident that I have some ways to go before I reach the convergence. (The curtain clouds appear to be further west than Nederland although differences in distance between clouds and ground features can be hard to judge. Looking for cloud shadows may help make this assessment.) Also, it is critical to consider that the lift will not be directly underneath the curtain clouds but to the west of them!

(4) As you head further west, pay very close attention to any lift or sink and commensurate changes in your altitude and formulate a Plan B and a Plan C in case you don’t find the expected lift.

Knowing where lift and sink are can become critical if you are not successful finding a climb and have to head back east. On days with sink you will need a much bigger safety margin than on days when the air is generally good.

In this picture I am now west of Nederland and rapidly approaching the curtain clouds. Note that I am at 10,700 feet. This feels quite low for the location where I am flying and I am mentally prepared to turn around immediately should I hit any sink.

However, I draw some reassurance from the fact that I only lost 300 feet since leaving the cloud near Gross Reservoir – seven miles further east. The rim of Boulder Canyon is at 8,500 feet – this means that even if I lost more than 1,000 feet heading back east , I would still be more than 1,000 feet above the Canyon rim. On some days (e.g. west wind days with the potential of wave or rotor) this would not be an acceptable margin at all but given the specific conditions of the day I decide to continue towards the west side of the curtain cloud and pledge to turn around as soon as I drop below 10,500 ft.

Note: I find it very important to always consider my safety margins well before approaching a critical decision point. Key factors that go into the decision are (1) the day’s conditions, (2) my skill, experience, and recency level, and (3) the performance of the glider I’m flying. I like to set hard rules for myself before approaching a somewhat marginal situation so that I won’t hesitate to take action before the situation becomes unsafe. (I also had a Plan C – to land at Caribou Ranch – in the worst case scenario of hitting substantial unexpected sink on the way back east.)

(5) Know where you need to be to connect with convergence lift.

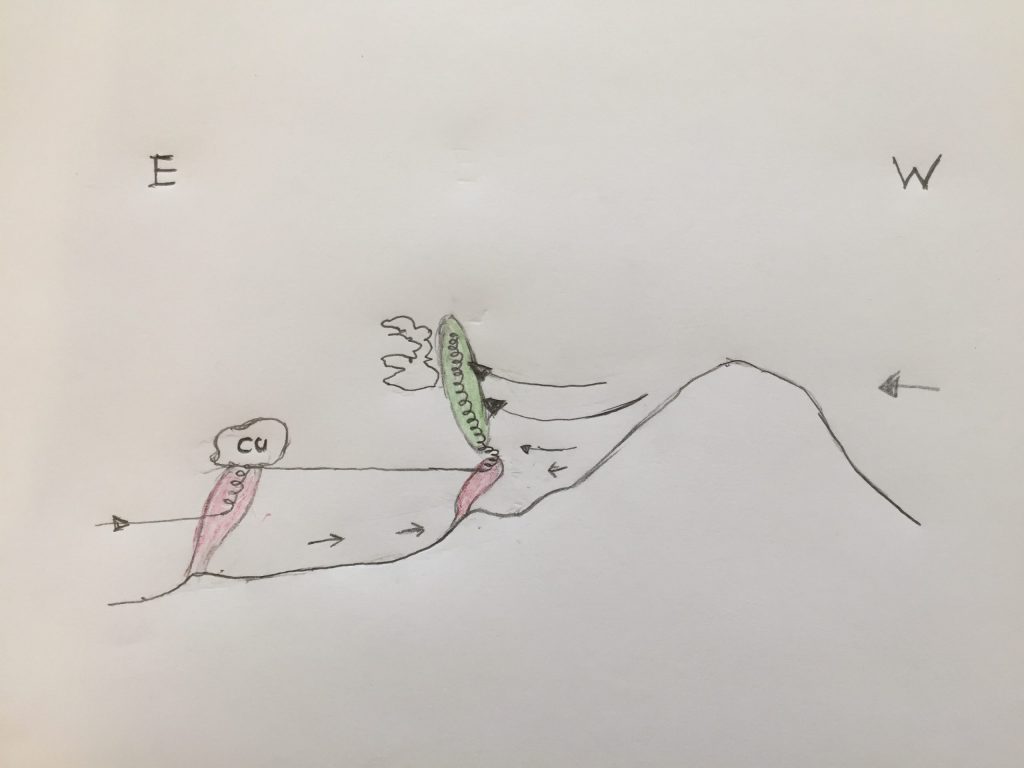

The following sketch illustrates how I think of the process of getting connected with convergence lift.

The glider is approaching from east to west. It climbs in thermal lift (shown in red) under a cumulus to cloud base somewhere over the foothills. From there it keeps pushing further west in the hope to reach the convergence lift (shown in green).

The scraggly curtain cloud is shown to the east of the convergence lift. The curtain cloud always forms at the edge of the two air masses. The eastern air is typically more moist than the western air. Therefore the cloud forms on the eastern side. The best lift is always west of the curtain cloud because the curtain cloud forms where the eastern airmass blocks the dryer western air from advancing east. I think of the curtain cloud as a barrier for the westerly wind: the west wind has to move up in front of the barrier almost like it has to move up along a mountain slope when you’re flying in ridge lift. (This isn’t entirely correct because the eastern airmass is obviously not as solid as a mountain but this model is very helpful in establishing a mental framework for what’s going on.)

Note that convergence lift is very unlikely to come up from the ground because it forms as a result of two wind streams coming together. At ground level there is too much friction and turbulence to form usable lift.

This means that the key to connecting with convergence is to be high enough to get into the (green) convergence zone. If you’re not high enough you will not find a climb.

It is therefore important to take every opportunity to climb as high as possible when you are close to the convergence. In the illustration I have shown a thermal (in red) just below the convergence lift. The glider enters the thermal and climbs up to the top of the thermal.

You’ll often notice that at the top of the thermal the lift becomes very weak and unorganized because it gets sheared off by the west wind and and the air becomes more turbulent. But very often you are now right at the cusp of making it, and with a little bit of luck you can continue your climb into the convergence.

When you analyze your flight afterwards you’ll notice that the wind drift in your climb changes half-way through. As long as you were in the thermal, you kept drifting from east to west and as soon as you enter the convergence lift, the wind drift changes from west to east.

In the picture above I am approaching the top of the thermal that is right below the convergence. The wind drift is still from east to west. Seconds later, the climb rate weakens as wind shears the thermal off.

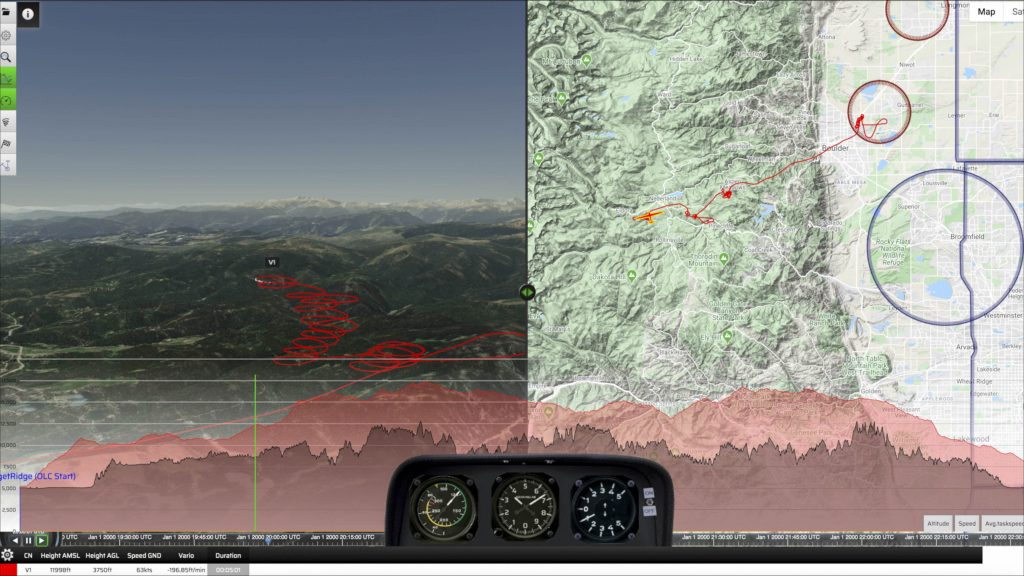

In the post flight analysis you can recognize the change in the wind drift half-way through the climb. (You can best see this on the left side of the chart above that shows a 3D image of the climb. Note how I drifted from left to right (east to west) in the bottom half of the climb, and how I started to drift right to left over the past three circles.)

(6) Be careful to conserve and top up altitude until you are solidly connected.

The illustration above has shown why a minimum altitude is critical to reach the bottom of the convergence.

One complication can be that the first contact with convergence may not be good enough to let you climb much higher. If that is the case, you need to explore nearby to see if you can gain more altitude before you start to fly along the convergence.

If the convergence line is marked by clouds this should not be too difficult. Look for any signs of air moving up and make your way to the upwind side of such markers.

In the picture above I am heading to the upwind side of the curtain cloud just to the left of the nose.

I turned as soon as I found lift and climbed up to 14,000 feet MSL.

You can now see that the wind drift is much more significant and firmly from west to east. This is a clear sign that I am now established in the convergence.

(7) Once you’ve made it, everything becomes easy: just follow the line on the upwind side!

Depending on the strength of the convergence, you may be able to cruise fast in straight flight without circling at all. Always stay on the upwind side of any marker clouds! If the convergence softens, you may need to decrease your cruising speed, and if the convergence is weak or if there are big gaps in the line you may need to stop in stronger lift from time to time to top up altitude.

In this picture I am cruising northbound along the convergence from Mount Evans to Longs Peak. I flew the entire ~45 mile stretch without a single circle and lost only 2,300 feet – an effective glide ratio of almost 100:1 at about 80-90 kts. Not bad!

(8) Make sure you don’t fall out of “the band”.

We’ve discussed earlier that convergence typically does not reach all the way to the ground. Therefore you must maintain a minimum altitude to stay in convergence lift.

The flying technique is similar to flying in ridge lift. The best lift along the ridge tends to be at ridge top – not higher and not lower (unless there are differences in the steepness of the slope). In convergence lift there is obviously no visible ridge top but I found that the lift tends to be best somewhere between the bottom and the top. It rarely pays to fly at the top of the lift band because the lift tends to be weaker. And you have to be very careful not to drop too low and fall out of the band! (If you do, you have to begin the process of climbing up into the line all over again. This is likely just as difficult and time consuming as it was when you entered the line and if the conditions change it might even become impossible.)

Be particularly careful if there are big gaps in the line of curtain clouds. Sometimes such gaps are just the result of reduced moisture and the convergence lift continues unabated between the clouds. But sometimes gaps can also mean that the lift line itself is interrupted.

Approach such gaps with some caution and think of them as transitions, just as you would approach gaps along a ridge line. You do not want to keep pressing ahead at full speed and then arrive at the next marker cloud too low to reconnect.

(9) Watch the lower lying clouds and always maintain an escape route

Flying in convergence may allow you to fly much higher than the cloud base on the downwind side. In this sense, it is similar to flying in wave. Always observe what is happening below you, especially if the cloud layer is becoming thicker and more dense.

On Saturday, the convergence line moved further west during the day and ended up directly above the spine of the Continental Divide. At the same time, upslope conditions over the plains caused increasing low level clouds to the east. When the sky to the east looked like this I decided it was time to pull out the spoilers and begin my descent below the lower lying clouds to the east.

(10) Have fun and fly safe!

Convergence conditions offer some of the most rewarding soaring in Boulder. Flying in convergence is easy and fairly safe provided you stay away from other aircraft (a transponder and Flarm are highly recommended). However, as discussed earlier, getting into the convergence can be fraught with risks – especially if the convergence line is west of the Peak-to-Peak highway and the thermal lift to the east of the line does not extend much beyond 11,000 feet.

I’m always trying to set safety margins that are appropriate for my skills and experience, the performance of the glider I’m flying, and the conditions of the day. A large percentage of accidents happen because pilots delayed a critical decision and found themselves in situations that simply offered no safe way out. Know your margins and always maintain a Plan B and a Plan C that you know you can execute safely if necessary.

My flight track is here.

A link to the video of the flight (with explanations) is here.

This is great stuff! I’m stumped as to how are you getting the flight analysis screenshots. I have SeeYou but cannot get my display to look like this in the cloud or PC version: https://i0.wp.com/chessintheair.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Screen-Shot-2020-05-12-at-1.29.19-PM-scaled.jpg?ssl=1

I see. About Me ->My Tools. http://www.soaringlab.eu. Have not heard of that previously and will try it out. Price is nice.

Hi Lon, yes, you found it! For me soaringlab compliments but does not replace SeeYou. The graphics are great, especially the quality of the maps. Glad you liked the article.