I’ve had a few days to ponder another failed Diamond Distance attempt on August 6 and reflect on what prompted me to abandon my task very early on a promising looking day.

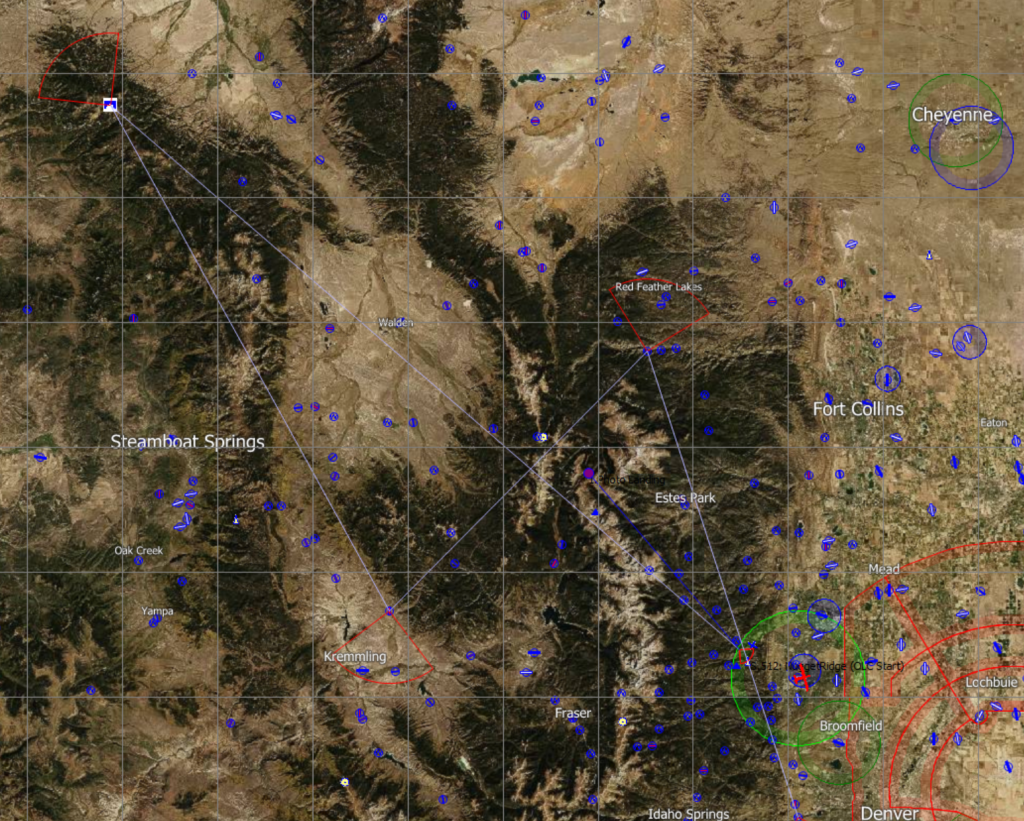

The weather forecast was strong, particularly to the northwest, and I had set an ambitious task with the first turn point at Bridger Peak, 40 miles south of Rawlins WY, and halfway between the airports of Saratoga, WY and Dixon, WY. To get there I would have to cross the Continental Divide into North Park, fly across North Park and then continue along the next mountain range to the northwest. The direct air distance from Boulder is 125 miles. The road distance is more than twice that, and driving there takes about 5 1/2 hours.

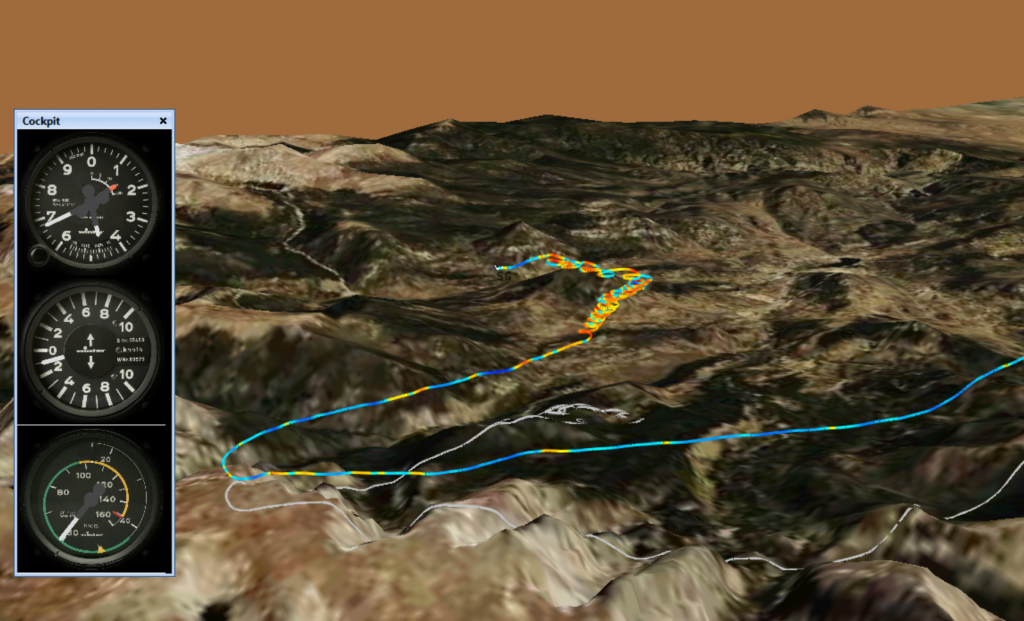

I had a good and early start after releasing from tow south of Coal Creek Canyon (between Boulder and Golden). I then climbed to 16,000 feet over the Flatirons, quickly crossed my start line and headed in north-westerly direction. It was still early in the day with few clouds. My immediate objective was to find a good spot to climb up to the Divide and then cross it at a location that would give me a safe passage into North Park. The best area for that seemed to be northwest of Estes Park.

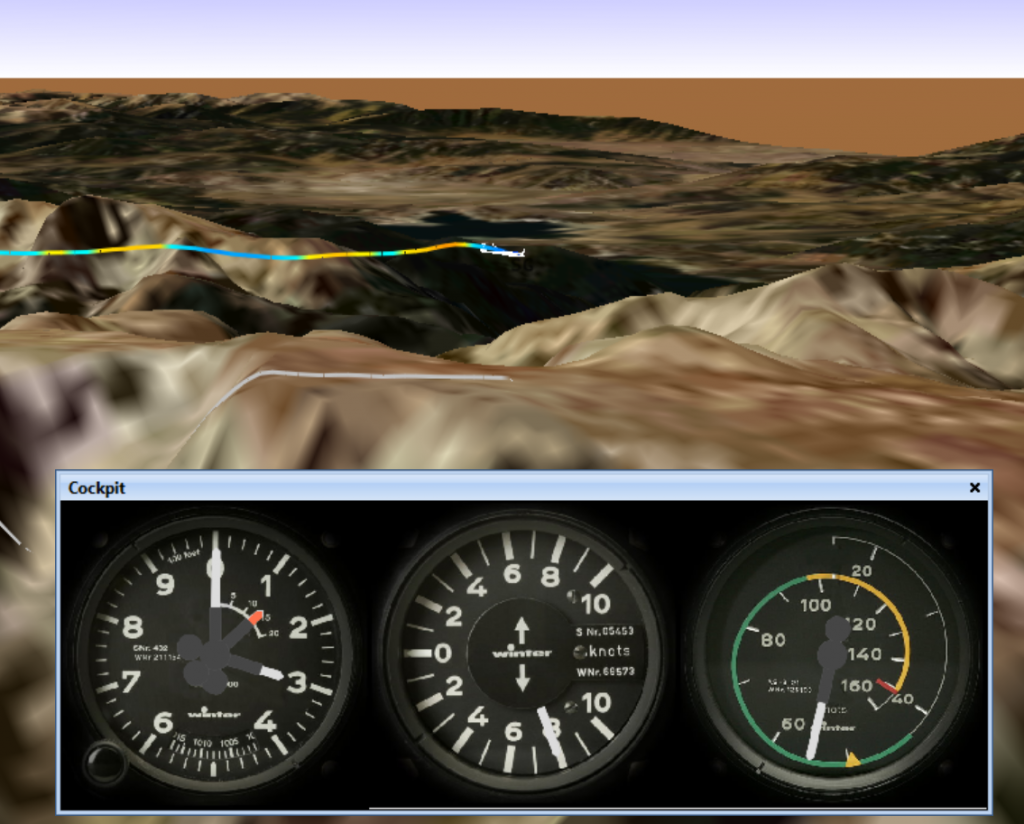

A few miles to the east of the Twin Sisters I found a strong 6-7 kt climb to cloud base at 16,400 ft and headed west from there towards the Divide. Although the cloud bases were still relatively low, my last few climbs had been good and I felt fairly confident that I would find good lift as soon as I would reach the Divide. So far everything had been quite easy.

That’s when my troubles began. The 12 mile push through the lee cost me more altitude than I had expected and when I reached the Divide above Flattop Mountain my altitude had dropped by more than 3,000 feet. I was down to 13,200, which put me at only 900 feet above the ridge. I remember thinking, “there has to be a climb here” and, “what do I do if there isn’t”?

The airport of Granby was in glide range. But the conditions in the Granby Valley, which I could now see for the first time, looked unsoarable and cloud bases there were very low, probably well below 12,000 feet. I felt almost certain that diverting towards Granby would mean accepting a retrieve.

The direction towards North Park looked much better but I first needed a good climb to get there.

Except for the escape route to Granby, 13,000 feet was not a comfortable altitude at my location. The nearest airport to the east was Vance Brand, 30 miles away and there was a lot of high terrain in the way. Fort Collins was 35 miles away, also with high terrain to clear east of Estes Park. I had to decide quickly what to do if I didn’t find a climb fast: turn west, which would almost certainly end with a landing in Granby, or turn back east, find lift or risk having to land in a field near Estes Park.

I still had a high degree of confidence in the thermal conditions to the east. And, very recently I walked a field at the base of Lumpy Ridge, less than 2 miles north of the town center of Estes Park. While I was not thrilled about the prospects of potentially having to end my flight there, I felt reasonably confident that I would be able land in that field without damaging the plane (or myself) if I really had to.

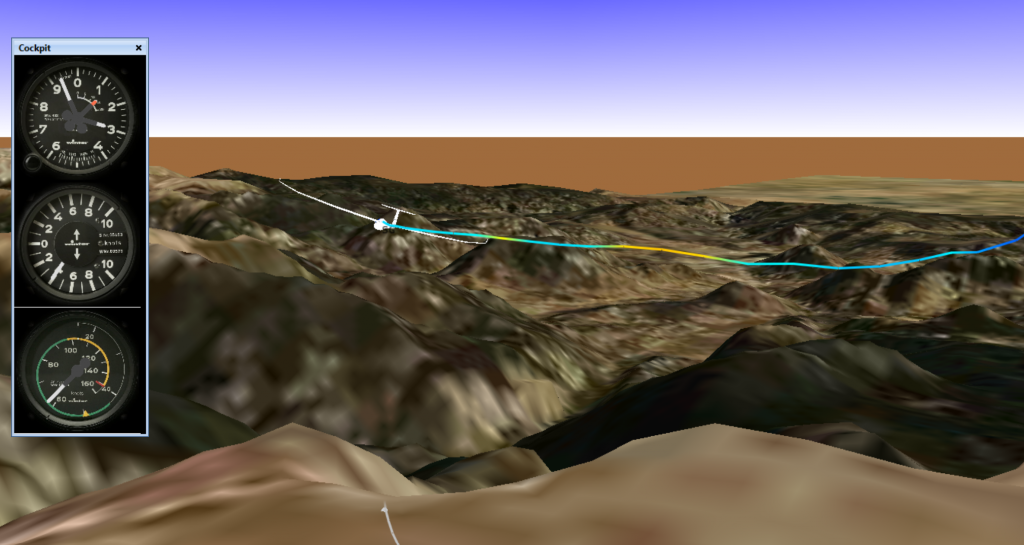

All this went through my mind in the one minute that I flew along the ridge looking for lift. Lift did not come and I ran out of time. A decision had to be made: turn left to Granby and land or turn right towards Estes Park and look for a climb? I turned right.

I still remember vividly the moment when I had to make that decision. Was it a risky choice? Subjectively it felt that way. Objectively, it probably wasn’t. I was at 13,000 feet. The field in Estes is at 8,000 feet. That meant I had about 4,000 feet of altitude to work with before I would have to decide to land. 4,000 feet gave me about 20 minutes to look for lift, maybe more. I had found strong lift several times that morning already and the conditions in Estes did not look any worse than the ones I had been soaring in for the last hour. And I now had a plan B, i.e I knew where I would land if I had to.

I followed a sun-facing ridge line towards Estes and, fortunately, I only needed a little more than one minute of my 20 minute lift-searching-allowance before I found the climb I was looking for.

Eight minutes later I had climbed back to 14,800 feet and the world was once again a better place. But the climb had been odd: between 12,400 and 14,100 the wind drift had been from west to east, and from 14,100 to 14,800 I had to push west to stay in lift and the climb became very uneven. That also meant the average climb rate was only 3 kt, the worst of the day thus far.

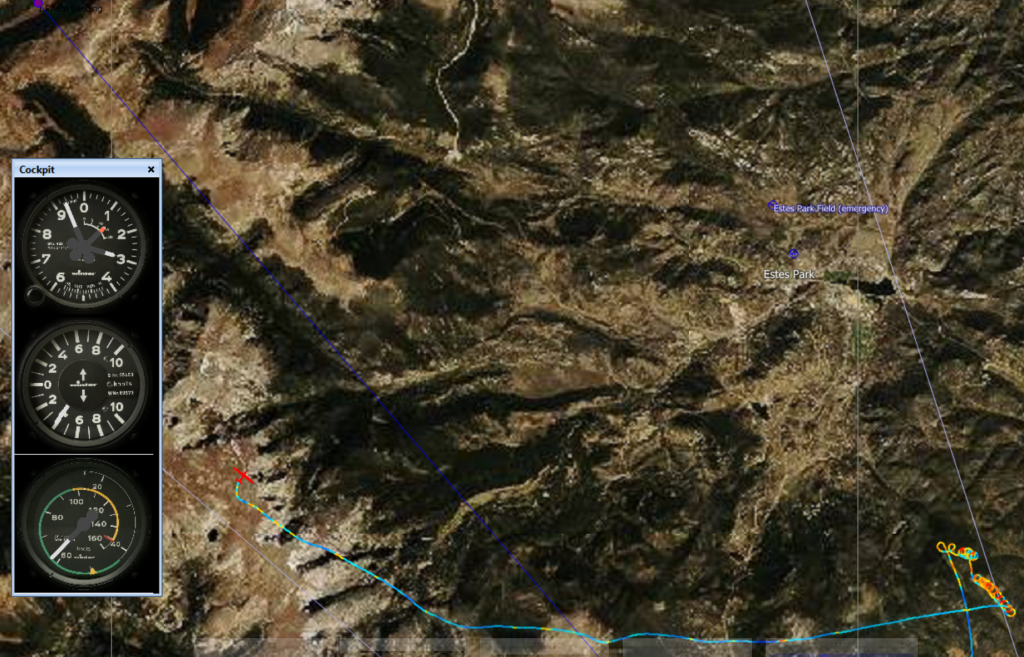

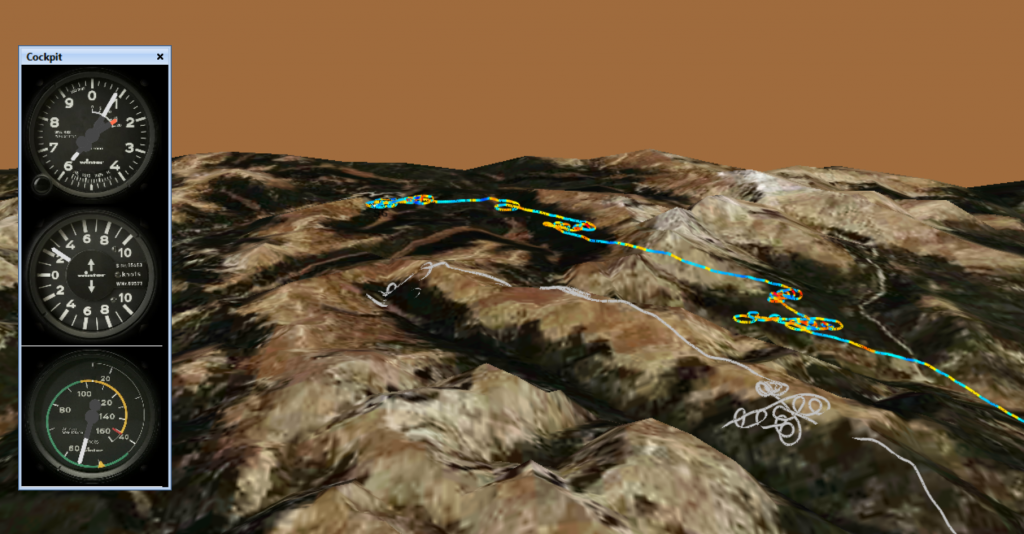

I quickly put that aside, given that I could not be choosey in picking this climb and pushed west again. Determined not to get so low again, I tried to take the next climb but it was very windblown and difficult to center. This time, I only managed to average 2 kts but managed to climb to 15,700.

A few miles further west, I once again only found very poor lift, taking me from 15,000 to 15,600 and the climb rate was less than 1.5 kts. Then, another few miles further west, an even weaker climb topped out at 16,100. That was the highest I could go.

I was clearly high enough to push into North Park and there were clouds on route but I hesitated. And hesitated. I could get there but would the lift be any better than my last 4 climbs, which were extremely poor and got worse as I moved west?

The top of the Divide can be very windy and the thermals there are often weak and uneven. Maybe, even probably, the conditions would be better if I went on. But I did not know that. Would the clouds work? I wanted to try it and then return if they didn’t work as well as I hoped. But maybe I wouldn’t even be able to come back? In which case I would likely be landing in Walden.

On the horizon, exactly in the direction of my first turn point, I could now see a towering cumulonimbus cloud billowing up. It was only 12:30pm. That seemed like an early indication of potentially massive overdevelopment in the afternoon. The forecast had not projected any storms but what about this cloud? It certainly looked threatening. Forecasts have been wrong before.

Circle by circle I was going back and forth in my mind. Should I push on or should I return? I already had my dose of adrenalin earlier when I got low above the ridge. The probability of completing the task seemed like a coin-toss. Maybe it would work, maybe not. Another circle of indecision. Then another. And another.

I looked towards Granby again where conditions had markedly improved in the last 20 minutes but the bases were still lower than to the east and northwest and the cloud bottoms still weren’t particularly promising.

My mind had finally found enough reasons “against” pushing across. In the next circle, I exited towards the south, having abandoned my task.

I went on and had a good flight on the east side of the Divide, but for the rest of the day I kept second guessing my decision. I watched the day improve. Cloud bases rose as one would expect. The weather never overdeveloped except for a few localized virga and showers. In hindsight, I am almost certain that completion of the task would have been possible. But you have to make these decision in the moment and with information available at the time.

To be clear, the decision to abandon the task was not due to a real or perceived safety risk. There was no question in my mind that I could reach the airport in Walden or at least another safe landing place. So the risk I was not willing to take was a sporting risk, not a safety risk. It was one of potential inconvenience: finding myself sitting on the ground in Walden, having to wait for a retrieve, if things didn’t work out.

The real question is of course: what will I do next time when completion seems uncertain? How confident do I have to be in my ability to complete my task? I must be honest: there will never be 100% certainty. Does it make sense to push on if the chance of completing the task is only 25%? Probably not. If the chance is 75%? Probably. If it is 50%? I still don’t know.

My flight track is here.

Lessons Learned

- 13k MSL Can Be Really Low. It always depends on where you are relative to safe landing places and any terrain in between. 13k above the Divide west of Estes Park is too low for comfort. I should not let this happen again.

- Walking Fields Pays Off. Having walked the field at the bottom of Lumpy Ridge, I knew where to find it and how to fly an approach if I needed to. This gave me the confidence to look for lift where I was almost sure to find it, and the clarity of thought to look for it without stressing out over whether or not I would be able to glide out to the prairie. Had I not known this field, diverting to Granby would have been my only viable choice.

- Don’t Ever Get Into a Marginal Situation without a Pre-Decided Plan B. When I approached the Divide I was so confident that I would find lift on top that I had not pre-decided what I would do if I that did not materialize. So I only had one minute to consider my options. This felt too short and too stressful. It’s best to make a Plan B while you still have a lot of options so you just have to execute what you already decided. (This is no different to the decision of what to do in case of a rope break or any other emergency situation. Don’t wait to decide what to do when it happens. You must know what to do in advance.)

- Don’t let your most recent experience in a small area cloud your judgement (recency bias). The day started very strong with solid, reliable climbs along the foothills. When the small area immediately next to the Divide did not work well, I lost confidence in the conditions across the divide as well. Similarly, I did not anticipate that the Divide would not work because I had found such great lift over the foothills. I must try to avoid falling victim of recency bias.

- Learn to better differentiate between safety risks and sporting risks. These are very different things. Never take safety risks.

- Pre-declare (to yourself) the level of sporting risk you are willing to take. Landing back at home is never 100% certain on a XC flight. It may be useful to pre-declare before the flight the land-out probability you are willing to take. E.g., “Today I am willing to accept a 30% land-out probability.” Then you can reflect during the flight what you believe the odds of landing out are if you continue on task. It might make it easier to decide whether to go on.

- Pre-arrange a retrieve in case you need it. There is huge peace of mind knowing that someone will come and get you if you have to land away from the home field. In fact, unless this is pre-arranged it’s really difficult to accept a significant land-out risk.

Sporting Risk vs. Safety Risk is a useful concept, but may be difficult to evaluate in flight. My self-evaluations tend to be much simpler. Ask yourself: Is this flight still fun? If the answer is “no”, it’s time to quit for the day, in as safe a manner as possible.