This past weekend marked the start of the 2018 OLC season for the Northern Hemisphere. For those who don’t know, OLC stands for Online Contest and is an informal worldwide soaring competition. Pilots anywhere can upload their flight tracks to a website hosted by a group of soaring aficionados in Germany. The tracks are automatically analyzed and classified according to the rules of various leagues.

My club, the Soaring Society of Boulder (SSB), is very active in the “OLC Speed League”. The Speed League runs on 19 consecutive weekends starting on the third weekend in April. Club rankings are determined based on the three fastest flights per club on any particular weekend during a 2 1/2 hour soaring window. You can read the full rules here. In 2017, SSB pilots won first place in the US Gold League and came in eight place worldwide (out of 1,162 participating soaring clubs).

Participating in this friendly competition seems to be a good way to track the progression of my own skill level over time when measured relative to the skills of much more experienced pilots. At the same time, I am acutely aware of the potential risks that participating in any kind of soaring competition could entail. I have written before about the risks of soaring, especially in a competitive setting, and ultimately it is up to the pilot to stay disciplined and put his or her safety firmly ahead of any competitive ambitions. This is the only way to stay safe.

Both Topmeteo and Skysight predicted weak to moderate thermals up to about 10-11k feet. A snowstorm had just dumped a few inches over the foothills the day before and – unsurprisingly – the forecast looked best for thermals over the plains that were sure to be free of snow cover.

A strong inversion lay over Boulder as I drove to the airport and the air was still on the ground. Speculating that conditions would likely improve later in the day I delayed my launch until 1 pm and watched other pilots take to the skies before me. The fact that most seemed to be able to stay up was encouraging.

Just before 1 PM I took off into the glider box just south of the airfield thinking that I would try to stay over the plains as the forecast suggested. However, as the tow plane climbed through 6000, 7000, and 8000 feet the air did not stir one bit. That’s when I got on the radio and asked the tow pilot to take me over the foothills where I saw that some white wisps had already started to form.

I kept my hand on the release ready to let go when I would notice a tangible updraft but the air remained still for a long time. We had climbed to almost 11,000 feet above Big Horn Mountain when I decided it was time to set myself free even though we had still not crossed a single patch of rising air.

I pointed the nose straight towards a tiny cloud that was forming above Gold Lake. Just as I hoped, I found the air stirring just enough to slowly gain some altitude back. I could also see a convergence line with a much higher cloud base several miles further west but getting there seemed very difficult or even impossible to me given the lack of usable landing spots over the foothills. With no other reliable options for lift in sight I decided to hold my ground for a while and wait for conditions to further improve.

After flying holding circles for almost 45 minutes a few additional small clouds had popped up here and there and I decided it was now or never if I wanted to get some cruising miles in.

The OLC rules require that the start of any flight has to be within 15 kilometers of the take-off airport. Gold Lake is 20 km away from Boulder and I could not remember whether I had released from tow before or after leaving the 15 km radius around the Boulder airport. So I decided to first head back and fly through the start cylinder near Lee Hill.

From there I returned to the area of lift near Gold Lake. Now I had to decide whether to go north or south. I remember flying several circles unable to decide. There was a promising looking cloud with a slightly higher base about 6 to 8 miles to the south but it was uncomfortably far away. If it did not work when I got there I would have no option but to bail towards the airport. There were a few smaller clouds to the north. Although they looked less compelling and had somewhat lower cloud bases they seemed to offer a more promising path forward overall. My indecision with respect to my course direction clearly was not a good tactical move: I had already crossed the start line, the clock was already ticking, and I was just staying in place…

If took me almost 15 minutes to make up my mind but eventually I decided to take the route to the north. Once made, the decision felt liberating for now I had a direction and a plan I was going to pursue. Why could I not decide quicker?

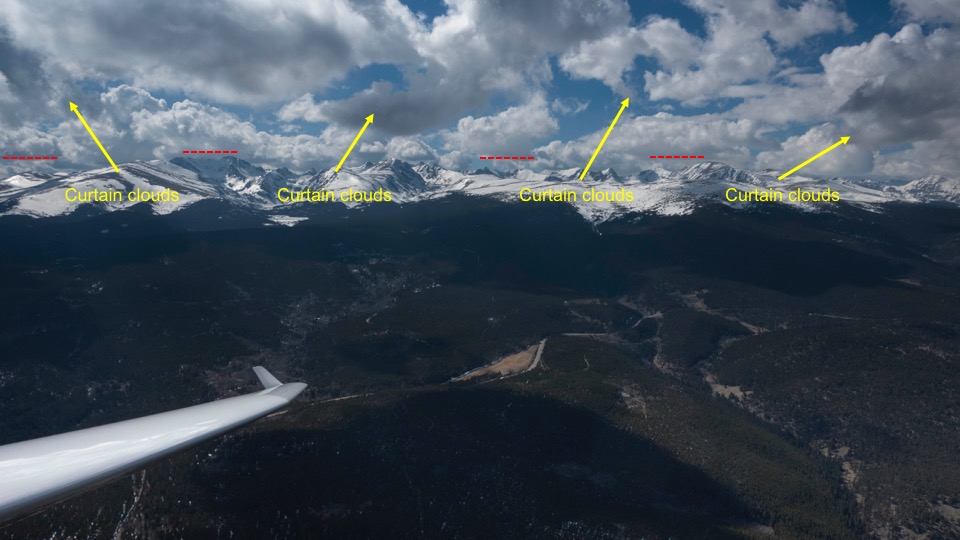

As I headed north towards the Twin Sisters I spotted some newly forming wisps that were about 2,000 feet higher than the cloud I had just left behind. It seemed like a long shot but I wanted to give it a try. I thought that if I could gain another 2,000 feet I might be able to get under the convergence line.

However, as I crossed the area below these wisps there was nothing but sink. There went my hope for reaching the convergence. Fortunately I had already worked out a plan B and a plan C. Plan B was sufficient. A small cloud above some rocky outcroppings north of Cabin Creek allowed me to get back to cloud base at 10,800 feet and to continue my track to the north.

I headed toward another small cloud just across US36 between Lyons and Estes Park. My Oudie indicated that my altitude was now barely enough to make it back to Boulder. The cloud worked again and provided the strongest lift of the day with an average of almost 4kt.

This allowed me to keep going a little further north until I reached a point between Estes Park and the north side of Carter Lake where my Oudie indicated an arrival altitude above Boulder just below pattern altitude. Considering the generally weak conditions it felt the right time to turn and head back south.

I followed a similar route on my return leg tracing along the most promising little clouds. I made sure to maintain a reasonably comfortable altitude above the undulating terrain, rarely dropping below 1,500 feet AGL and never below 1,000 feet AGL. I also always kept an escape path towards the plains and generally was within glide range of the Boulder airport (albeit sometimes with little margin).

Little by little, cloud by cloud, I made it to the town of Nederland, 30 miles from my turnaround point. It was already 4PM MDT and the clouds began to dissolve around me. So I decided that it was a good time to for a scenic cruise back to Boulder.I took advantage of the Discus’ 42:1 glide ratio and detoured via Gross Reservoir to Eldorado Canyon. From there I followed the ridge line of the Flatirons where I provided some entertainment for the hikers atop of Bear Peak. The easterly flow was unfortunately insufficient to maintain altitude when soaring along the ridge. (The windward side of the Flatirons was already in the sun shadow so I suspect any lift from the wind might have been negated by cool air descending the face of the mountains.)

Overall, this was a challenging but satisfying start to the 2018 OLC season. Looking at the score board of the OLC Speed League, my flight was just fast enough to qualify to be scored for the Speed League as the third of the three Boulder flights that count this weekend. (The Boulder pilot who flew the greatest distance yesterday did not fly through the start cylinder and consequently his flight doesn’t count for the speed league.)

A link to my flight track is here.

Lessons Learnt

- Safety First, Always. Not a new lesson but worth keeping in mind, especially when flying with a competitive streak. There is nothing to be gained in soaring competitions; however, many lives have been lost when competitors didn’t always put safety first. Only fools risk life and limb for no gain. So don’t be one.

- Always Keep a (Safe) Escape Path. The terrain over the foothills is tricky. Your computer may tell you that you are within glide range of the airport but it might not account for terrain that’s in the way. Be especially careful south of Nederland where there is higher terrain to clear to the east if you want (or need) to get back to the plains.

- You Cannot Fly In the Foothills, You Have to Fly Above Them. When flying in the Alps you often fly very close to terrain and most of the time the steep valleys provide escape routes into wider valleys with land-out options. There are no land-out options in the foothills and the canyons don’t provide safe escape routes into the plain.

- 1,500 Foot Ground Clearance Above the Foothills Feels Ok. 1,000 Foot Feels Low. That’s for a high performance ship such as the Discus. For lower performance ships, maintain more ground clearance. If the thermals don’t support it, get out of there while you can.

- Don’t (Blindly) Trust the Weather Forecast. Again. Both Topmeteo and Skysight had predicted the best thermals over the plains. In reality the plains – where the inversion was very persistent – provided only very weak lift up to 8,500 to 9,000 foot while the better lift was clearly over the foothills and mountains. (Much of the snow over the foothills was gone by early afternoon and the south facing rocks heated up nicely.) Skysight missed the convergence line along the divide. (Topmeteo does not predict convergence.) I will keep reading the forecast but always consider that reality is likely to be different.

- Good lift can often be found next to lakes. Today the first lift I found was next to Gold Lake. Two of my other thermals were next to lakes too. Most textbooks tell you to stay away from lakes but my (limited) empirical evidence suggests that the best thermals are often next to bodies of water. There’s also a great German soaring textbook called Meteorologie für Segelflieger by Henry Blum (Meteorology for Soaring Pilots) that convincingly argues that humidity enhances thermals and the best ones are often found next to lakes, rivers, or next to moist forests, mainly because moist air is lighter than dry air.

- Indecision Costs a Lot of Time. If I want to improve my performance for the speed league, I need to get better at making decisions based on the information available at the time instead of flying holding circles until I have made up my mind.