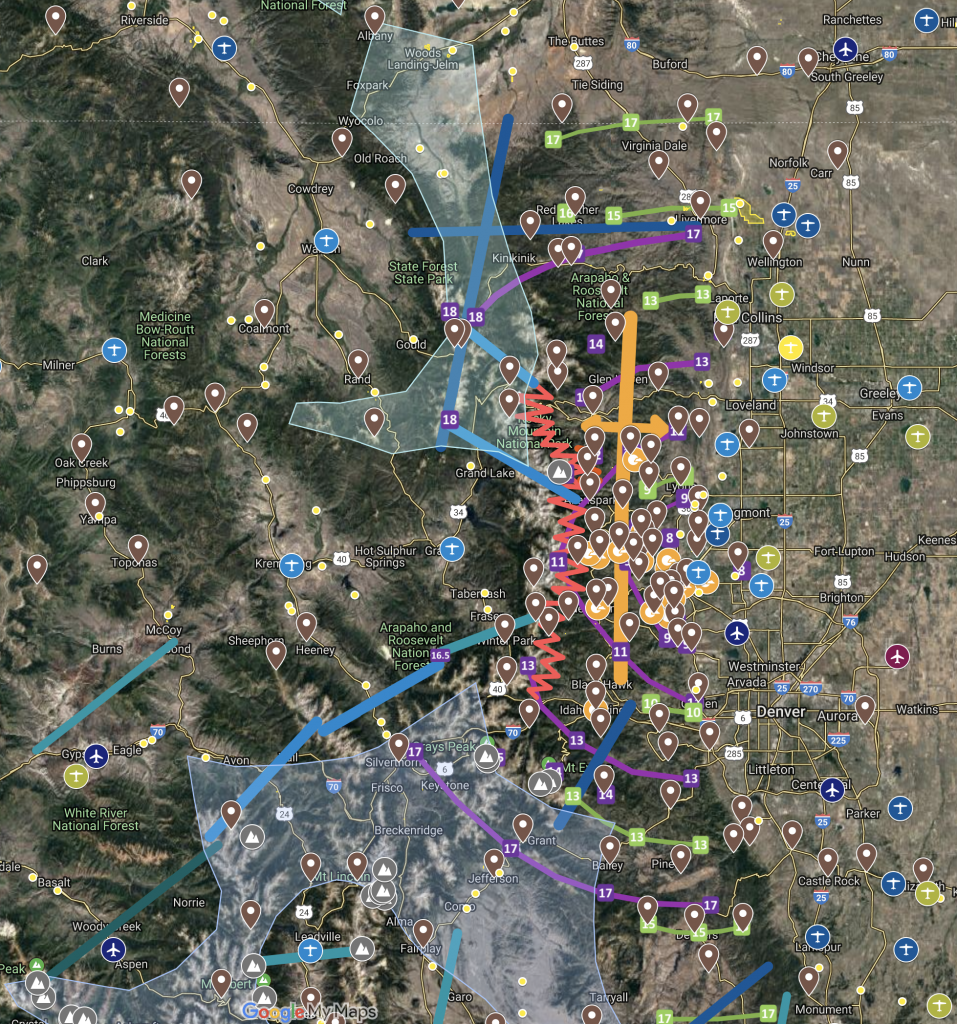

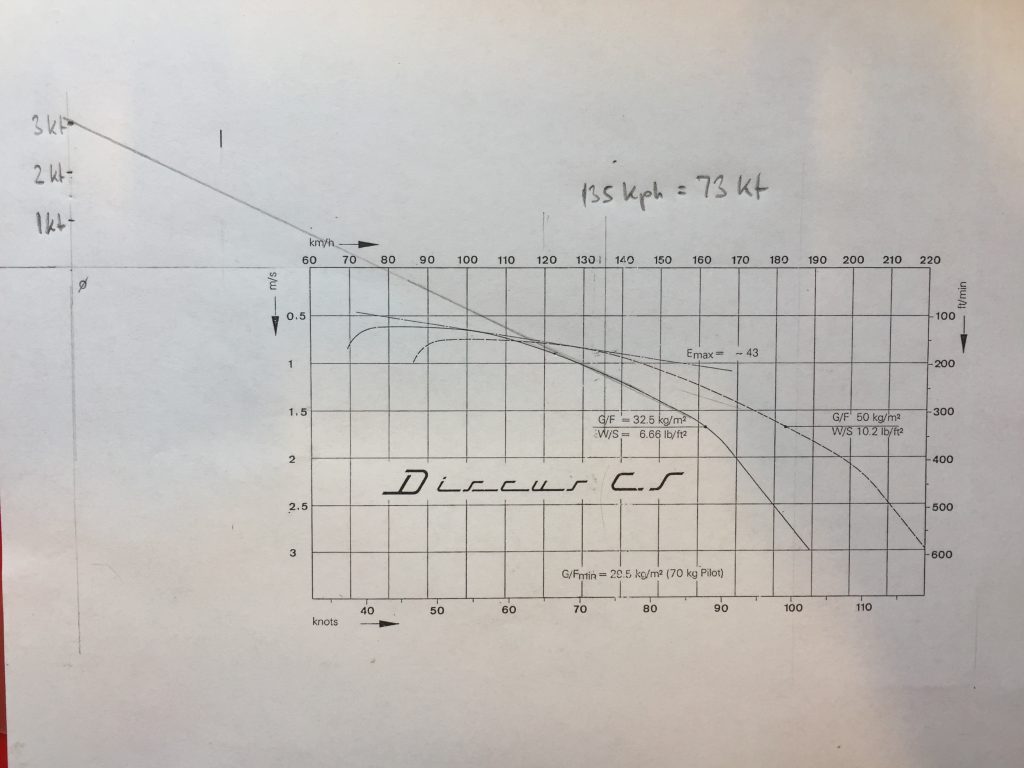

Recently I did a lot of work to update my Boulder 250 sm way point files, including the creation of this Boulder 250 Soaring Map with Final Glide calculations for typical second generation glass ships that would work for our club’s Discus and DG 505.

This past Saturday, I had a chance to test my final glide assumptions in real life.

It was a fun but challenging day for flying. A lenticular cloud shielded much of the area east of the Continental Divide from the sun all morning, causing the day to develop quite late, despite the unseasonally high surface temperatures. A cold front was forecast for the following day. In Colorado, pre-frontal weather is almost always associated with an unstable air mass and a risk of over-development once the sun starts to heat the ground. I expected that the combination of late sunshine and early OD would likely make for a relatively narrow soaring window. Skysight had projected this to be between approx. 1 PM and 4 PM (which turned out to be largely correct).

I launched at 1:20 PM after the first cumulus clouds appeared over the hills behind the Flatirons. For a long time the air was still on tow – the valley was still inverted. I towed right to the edge of the 15 km ring around Boulder and released in the first weak lift over Sugarloaf. (I later found out that I had released just a tiny bit too late to qualify for an OLC Speed League start so I should have “dipped back” into the 15km ring.) That lift disappeared quickly and so I headed further west to the nearest cloud, which was above the town of Nederland. I scratched around for almost half an hour until I found the first decent climb above the windward side of Niwot Ridge (the wind in this area blew at 10kt from the SE – ideal for the ridge).

There I climbed to 16,500 and was able to connect with a convergence-induced cloud street heading NNE. Finally I could switch to cruise mode. The street took me more than 40 miles in straight flight past Lookout Mountain NE of Estes Park. A wildfire north of the hamlet of Rustic generated a lot of smoke drifting east.

Unfortunately, the convergence line went right through the smoke. I did not want to fly into poor visibility and sought to make my way around the fire on the west side. The thermals in this area where weak and wind-blown with significant sink in the lee of Crown Point, one of the mountains along that stretch of the Continental Divide.

When I could not find a comfortable way to get past the fire without losing too much altitude, I reversed course and followed a cloud street back toward the Twin Sisters (S of Estes Park). The sky to the south was now fully overdeveloped and virga curtains ahead stopped my progress. I turned back again towards Poudre where the fire kept burning.

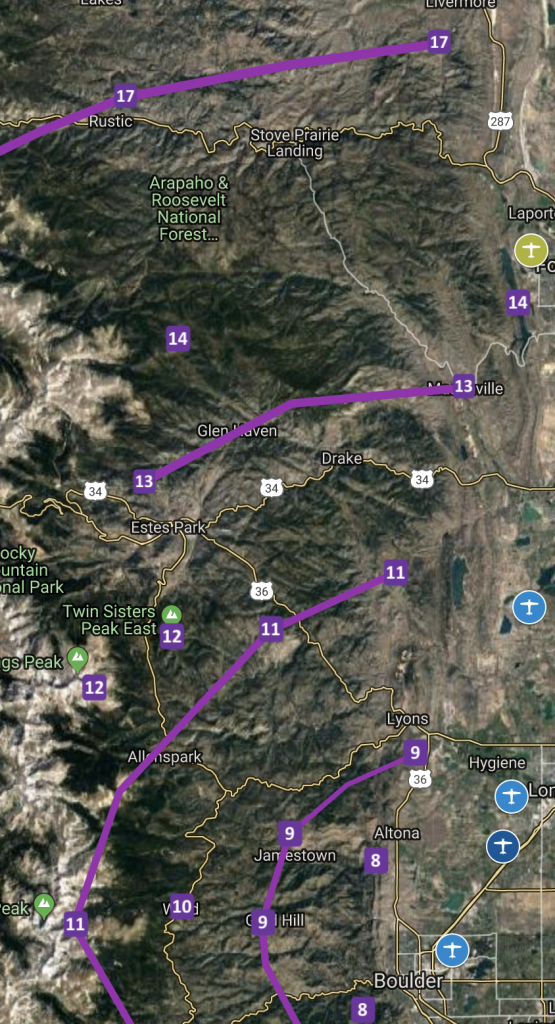

I made it all the way to Rustic on this second attempt, and was now finally able to get past the fire without risk of getting engulfed by smoke. However, the sky was now fully overcast in all directions with many virga to the south and some virga and rain further north. I wasn’t sure how long there would still be lift and so I prudently decided to head back to Boulder, 54 miles away.

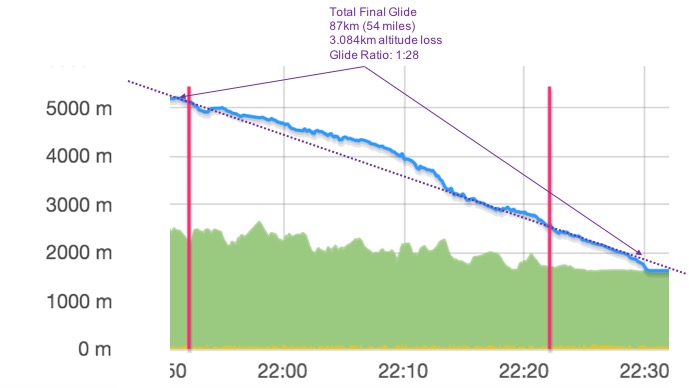

I was at 17,000 ft MSL above Rustic. From my work on the Boulder Soaring Map I knew that this was just the altitude I would need to get to Boulder airport and arrive there at 1,500 ft AGL, flying the Discus (without ballast) at 80 kts in still air (a glide ratio of 1:27). My flight computer, which was set to MC 3, suggested that I would arrive at 3,000 ft AGL, flying at around 70-75 kts.

There was a westerly cross wind of about 10 kts, which would negatively impact the glide performance, so I figured that 80 kts would be too fast. I decided to fly just at a little over 70 kts, and see what would happen. There were several airport landing options along the way (you can also see them on the map below at the eastern edge.)

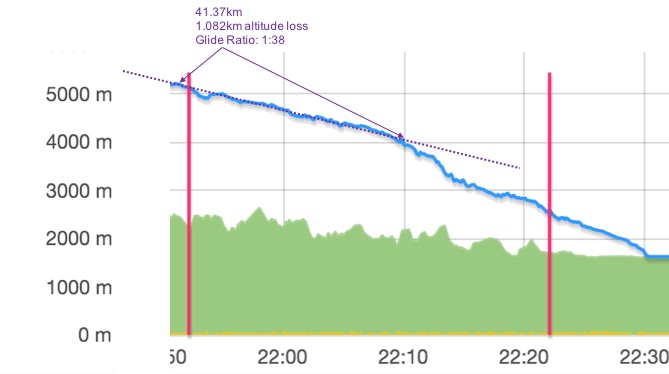

Things were going very well for the first 25 miles of the final glide. Instead of flying the most direct line I picked a path further east that connected several distinct clouds within the overcast layer. Pulling up a little into the wind whenever I crossed an area of lift I kept gaining several hundred feet on my arrival altitude even though my path represented a slight detour. When I crossed CO Rt 34 east of Drake, my flight computer predicted a very comfortable arrival at Boulder at 3,500 ft AGL.

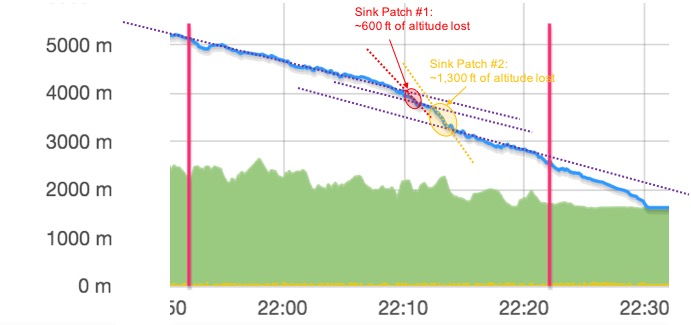

But just as I started to be very happy with my performance and secure in my final glide altitude (I later calculated that my effective glide ratio on this first part of the final glide was a remarkable 1:38 flown at an average ground speed of 76 kts), I hit two patches of sink in quick succession. The first one was relatively mild and lasted less than one minute. The second one came two minutes later as I was flying past Carter Lake, and was quite severe. The vario hit negative 10kts. I pushed the stick forward and accelerated to 100kts to get out of the predicament as soon as possible. Within 1 minute and 16 seconds I lost 396 meters (1,300 feet).

When the sink subsided and I had the airspeed dialed back, my flight computer showed a predicted arrival altitude of only 2,000 ft AGL. Wow! I had just lost 1,500 ft against my arrival altitude within about two minutes and my safety margin was getting thin.

I tried to make out what had caused the sink but no obvious explanation came to mind. I was well clear of any virga lines, I had carefully avoided the lee of Blue Mountain (west of Carter Lake) and the sky looked almost homogeneously gray. For the first time I felt no longer 100% certain about arriving in Boulder at a safe altitude. I took a good look at Longmont airport to my left, which was definitely within easy glide range at this point.

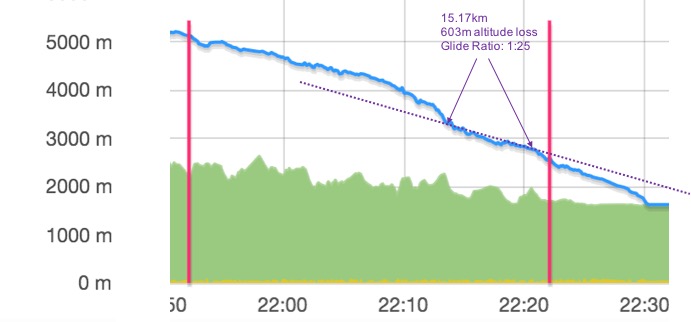

I continued ahead and resolved that I would fly past Lyons and decide then whether or not to divert to Longmont. Fortunately the next stretch of air was better with minimal sink and some small patches of weak lift. I passed Lyons at 9,500 MSL and shortly thereafter my predicted arrival altitude in Boulder had climbed back up to 2,200 AGL.

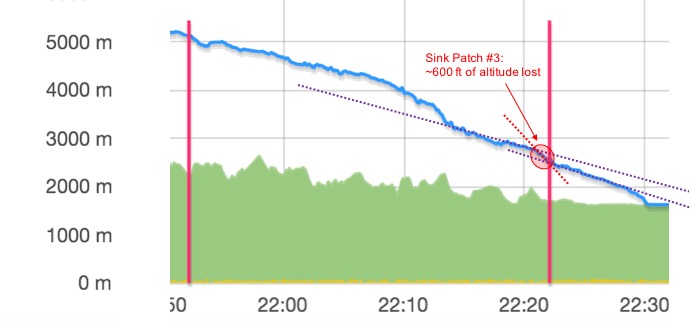

Just after I had decided that I had an adequate safety margin to continue on to Boulder, I hit another patch of sink near Altona with only 7 miles left to go. It wan’t as bad as the prior one, but another 600 feet of altitude were gone and my flight computer showed an arrival at 1,600 AGL.

Turning back to Longmont was no longer a sensible option for Longmont was now equidistant to Boulder and my way back would lead me through the same sink I had just crossed. I made some additional contingency plans: if I would find lift I would stop to re-gain a few hundred feet. If I were to lose another 800 ft against my flight path, I would enter the pattern from the north instead of the usual entry mid-field from the south. In the worst case, I would land in a field west of Boulder Reservoir. This final glide was definitely more exciting than I had expected!

Fortunately, the remaining part of the glide was uneventful without unexpected sink or lift and I did in fact arrive at 1,600 ft AGL; i.e. with plenty of altitude and time to examine the wind socks and traffic, and to fly a normal high pattern to glider Runway 26.

Overall, the final glide was 54 miles long (this includes a 5 mile deviation from the straight course), flown in 35.5 minutes at an average ground speed of 79 kts and with an effective glide ratio of 1:28. (Calculated over the most direct route the glide ratio was 1:26). The three patches of sink made the last 10 miles quite a bit more exciting than I had expected even though I ultimately arrived at a safe height of 1,600 AGL.

The flight track is here.

Lessons Learned

- The glide performance of the Discus seems to be right in line with the glide polar and the final glide rings on the Boulder Soaring Map work. But: the caveat that glide calculations only work if if the air is still is definitely true. It’s also good to remember that we only like to go soaring when the air is not still!

- Even on final glide it is critical to continue to examine the clouds and the terrain and to somewhat deviate from the straight line if appropriate. This way I achieved a glide ratio of 1:38 on the first half of my final glide. This allowed me to build up a significant safety margin which ultimately turned out to be necessary to counter the patches of sink during the second half of the glide.

- A patch of heavy sink can very quickly eat away a significant safety margin. The glide path looks very different after losing 1,500 feet in two minutes.

- Having acceptable landing options available as a contingency is absolutely critical on final glide. Knowing that Longmont was always easily accessible made me perfectly comfortable until I hit the second patch of sink near Altona, when suddenly Longmont was no longer an option. On any final glide the ultimate stretch after passing the last good land-out option will always be the most critical one.

- If I’m not racing, I’ll revert back to planning to arrive higher and go past the airport before coming back to the pattern. The extra excitement in the last few minutes is not necessary. 🙂

- On OLC speed league days I need to pay closer attention to my release point on tow and dip back into the 15km ring if necessary to ensure my flight counts. (It ultimately did not matter this past Saturday because three other club members had qualifying flights with a better performance.)