What do Colorado bears have in common with glider pilots? As soon as the spring sun heats the ground, and the ground heats the air, both come out of their dens.

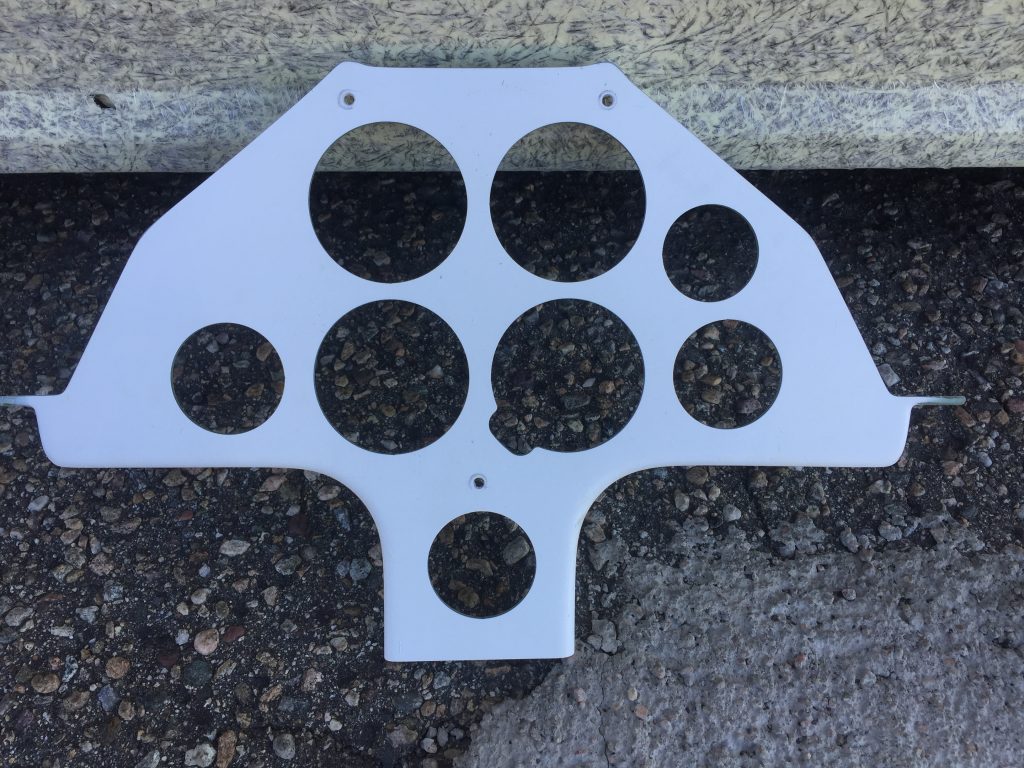

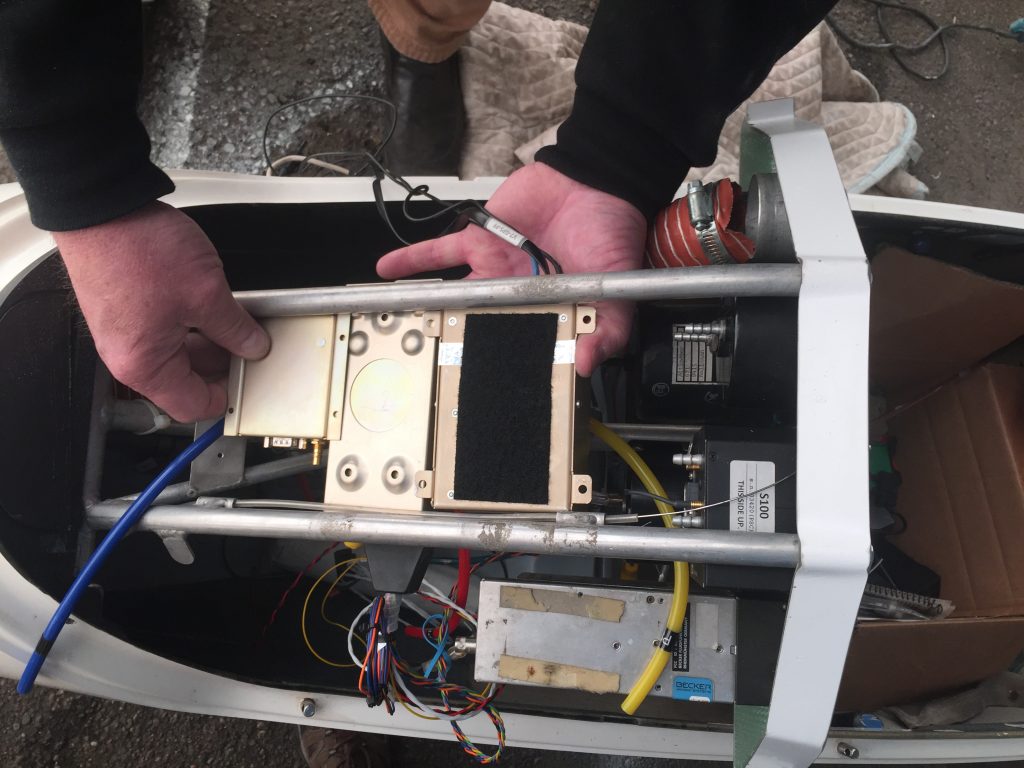

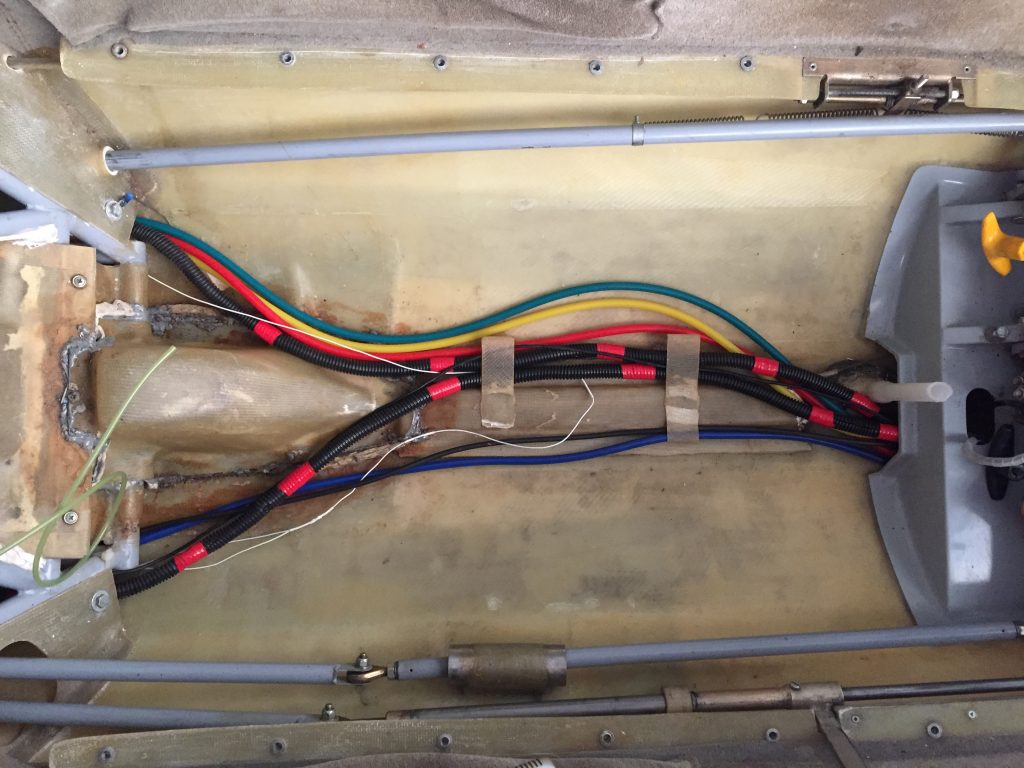

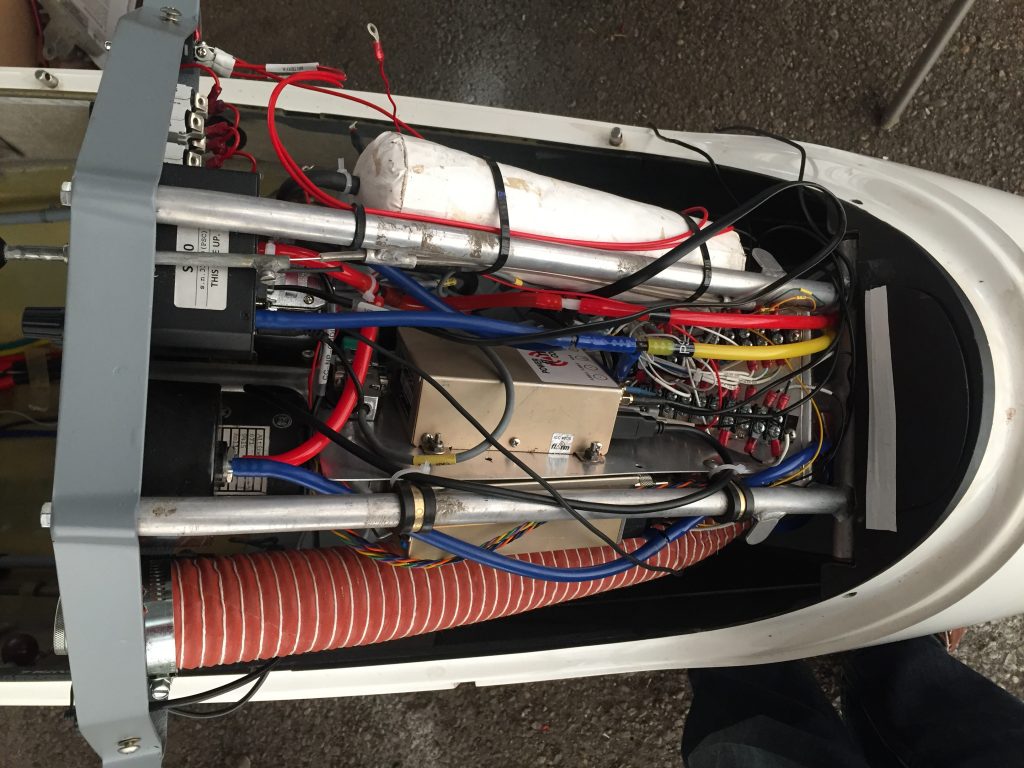

Except that for many of us glider pilots, our den this year was the hangar. And we didn’t get to sleep in. For the past 10 weeks several of us spent a lot of time redoing the panel on our club’s Discus CS under the tireless, thoughtful, and diligent guidance of Jack, our ship manager. Not even a broken leg would deter him…

Then, yesterday, finally, I had the honor of test-flying the ship. And voila, everything worked perfectly. All the little issues that had plagued the ship from time to time in the past such as erratic vario displays due to leaky tubing, power failures due to old batteries, poor radio reception, an unreadable flarm display, stick thermal indications due to faulty compensation settings, etc… all those issues where gone.

The new S100 flight computer, which isn’t just your task planner and speed-to-fly calculator, but which integrates every available information into a central hub is a thing of functional beauty. Other air-traffic, even commercial airliners, showed up on the display, color coded by height. I spotted glider pilots with their call signs on the screen before I could see them for real. The temperature sensor told me when I climbed to freezing altitudes, the gear warning was a friendly voice and not an obnoxious sound the meaning of which has yet to be deciphered. The thermal assistant provided timely and accurate information. The screen is super bright and easy to read at a brief glance even with my polarized sunglasses. Climb and sink indications agreed with the fully-compensated mechanical vario. I could just keep my eyes outside the cockpit, focus on the sky, the wind, and the sun and not worry about any of the little things that can become distractions. That’s soaring as it should be!

As always, the Discus handled perfectly. The coolest thing is that it basically thermals on autopilot. Whenever I put it in a 45 degree bank it just stayed there without further control inputs. You can even take your hand off the stick, adjust your oxygen cannula, take pictures and just make small corrections with the rudder pedals while the ship basically climbs on its own. You can just look outside and watch the world become smaller and smaller.

I want to thank everyone who’s contributed to this major club project. We have a fleet of terrific club ships, which only very few clubs in the United States can offer their members. Come out to the field and enjoy!

So here’s a bit about the flight itself: I got a late launch at about 1:35pm when thermal conditions were almost at their peak. As soon as I was satisfied that everything was working and that I wouldn’t need to test the parachute as well ;-), I released at 1,700 AGL and immediately climbed a few thousand feet off tow. The sky was mostly blue with a few clouds near Thorodin Mountain SW of the Flatirons. So that’s where I headed first. But all I could find was sink. I hadn’t even reached Gross Reservoir when I decided to head back to the prairie. The thermals were still there but the wind had started to shift to the west. That meant the climbs were less consistent and more wind blown with a somewhat “rotory” feel.

As a climbed, a line of small rotor clouds developed NW of the field to the west of Left Hand Canyon. I gingerly headed towards that line, pulling a little in every gust and pushing through any sink. I was able to connect with that line and then fly in cruise mode all the way to the ridge line NE of Estes Park. This was a good stretch to spot commercial air traffic inbound into DIA on the Flarm screen of the S100. It was very comforting not solely having to rely on ATC to see me, but to see the airliners myself on the screen before spotting them in the sky.

I found good lift on the ridge near Storm Mountain where I climbed above 14,500. The sky to the north from there looked pretty bleak, so I decided to retrace my track while another rotor line formed further east. I connected with that line between Carter Lake and Berthoud, climbed back up to over 14,000 and then imagined a straight line south from there with relatively good air. Although there were no clouds the line worked in reducing my sink rate and supporting my glide. I headed past Boulder and the Flatirons towards some rotor clouds north of Golden. These did not work at all, however.

I turned towards the Flatirons, intent on soaring along the top of the ridge where I expected significant ridge lift since the wind speed had picked up considerably and was now 20-30 kts from the west. Unfortunately the push through the lee and into the wind cost just a bit too much altitude and I was not comfortable with my height as I got toward the Flatirons. I remember thinking, “if this were Condor, I would just go for it, and I’m sure it would work”. But this wasn’t Condor, and in the real world I only have one life to live, so it was an easy decision to turn away.

I pushed through the heavy lee sink at about 100 kts and arrived at the field at a comfortable height of just under 2000 AGL. The wind was blowing straight from the west at 20 kts gusting to 25. A sporty pattern flown at about 80 knots brought me to a smooth landing after a flight of 2 hours and 15 minutes. At 168km it wasn’t particularly long, and at 78 kph it wasn’t particularly fast, but I’m satisfied that it was about what was reasonably possible for me with such a late launch and the onset of strong west wind conditions.

Finally, here’s a look at the new panel in flight as I’m cruising in good lift along the rotor line heading north. The small clouds in the distance (right in front of the nose) were my northerly turnpoint near Storm Mountain.

Lessons Learned

- It’s great to be in a club. I have learned so much from all the talented fellow club members during this project. Taking care of a glider felt intimidating to me and for many things I would not have even known where to start. Compared to my club mates I still know very little but at least I have a basic understanding how everything works and I have a reasonable idea as to what I can do myself and where I still need help. The whole thing is no longer a total mystery. And that’s huge progress for me.

- The flight controls of a glider are mechanical and quite simple; but the entire pneumatic, electric, and electronic systems are another matter. While only very little of it is needed to fly safely, it does make flying easier and more enjoyable because – when everything works – you can focus on what’s outside the cockpit and not worry about glide calculations or the accuracy of any of the instruments.

- The flight itself held some new lessons, too. I experienced the transition from thermal to rotor conditions and the effect this had on the thermals in the prairie. When I noticed what went on, I adjusted appropriately to the new situation and switched to “rotor flying”.

- Intent on circling as little as possible, I consciously practiced “feeling the air” as I was cruising along the rotor line. Whenever I felt some lift I would gently pull up into the rising air, and whenever I felt some sink I would try to gently push away from it with careful and limited control inputs. It’s hard to know if I did it right – that would have required another glider to my side flying straight at a constant airspeed – but my subjective feeling is that it worked quite well.

- When approaching the Flatirons with questionable altitude to get above the ridge I am glad I immediately made the right call without hesitation. I always worry a little that flying on Condor might teach me to take undue risks (I actually always tell myself on Condor that I would not do XYZ in real life whenever I approach a risky transition) and I’m glad the same thought came to me in this real life situation with the very clear opposite outcome that favors safety above everything else. I’m committed to keeping it that way.