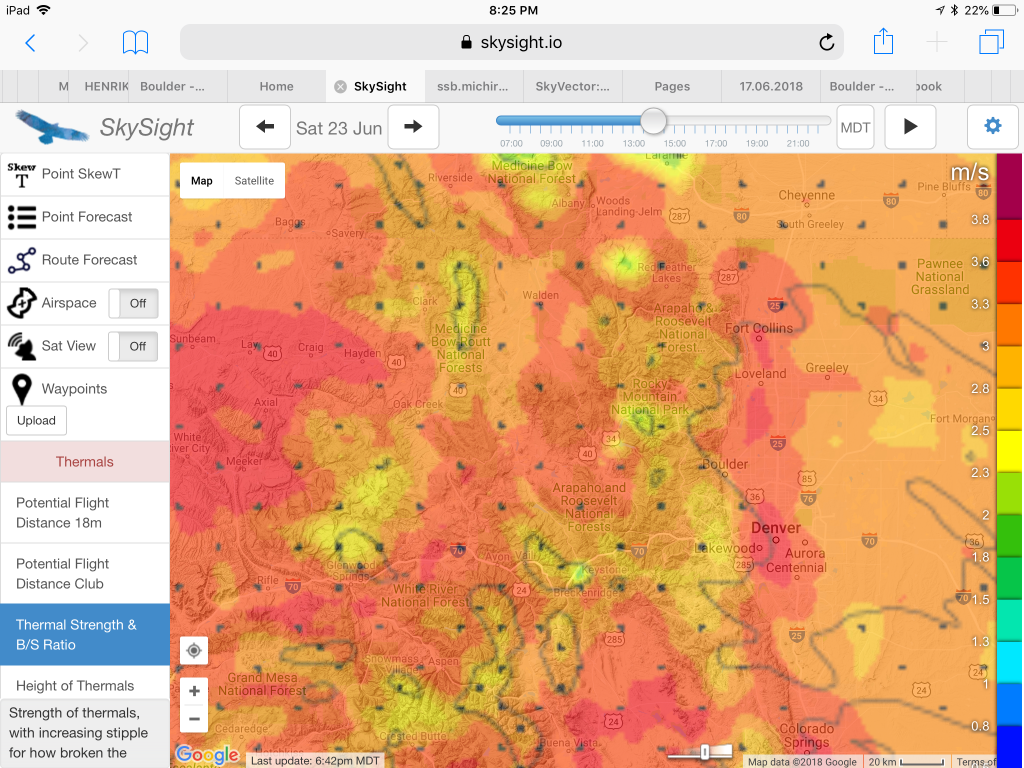

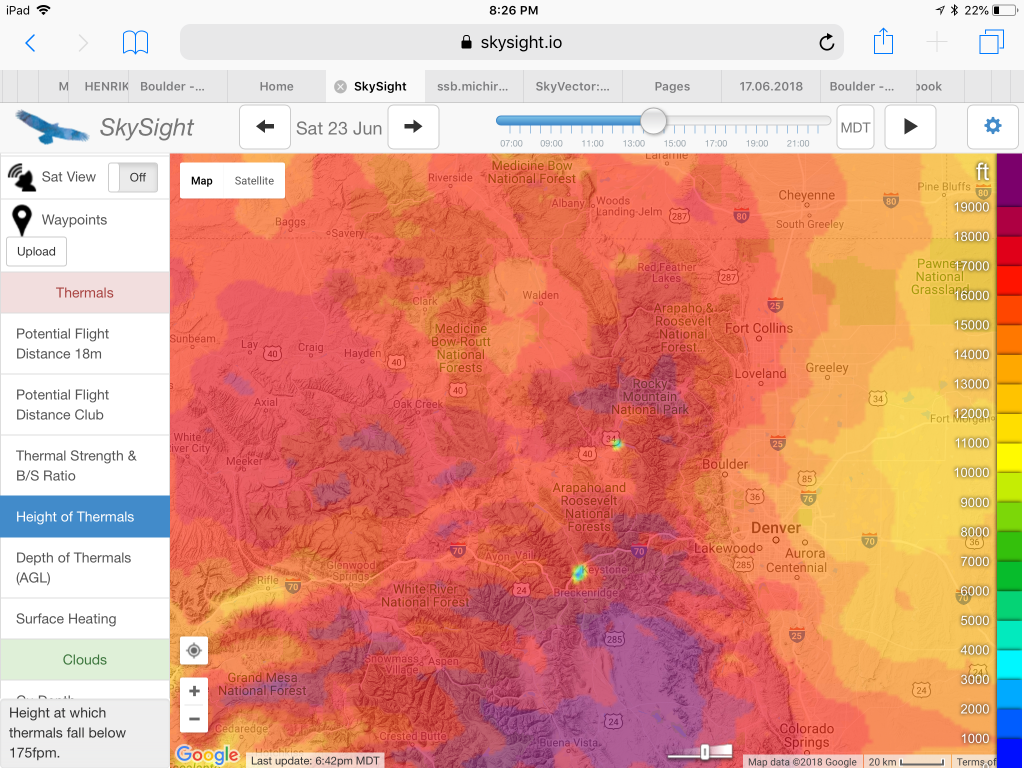

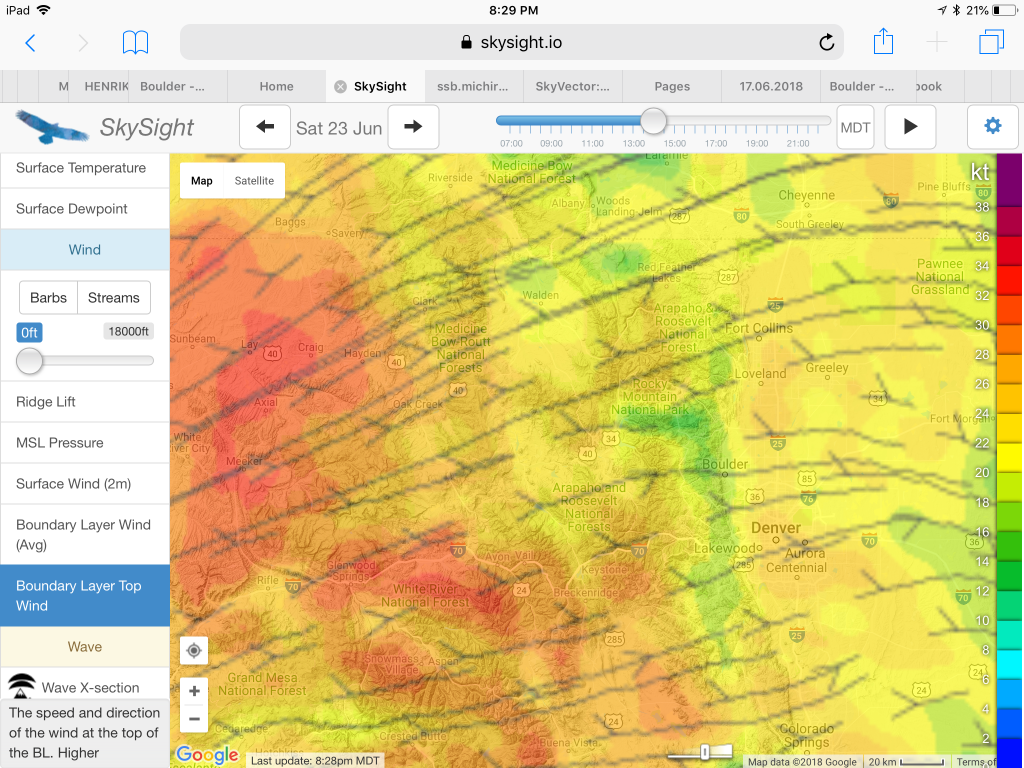

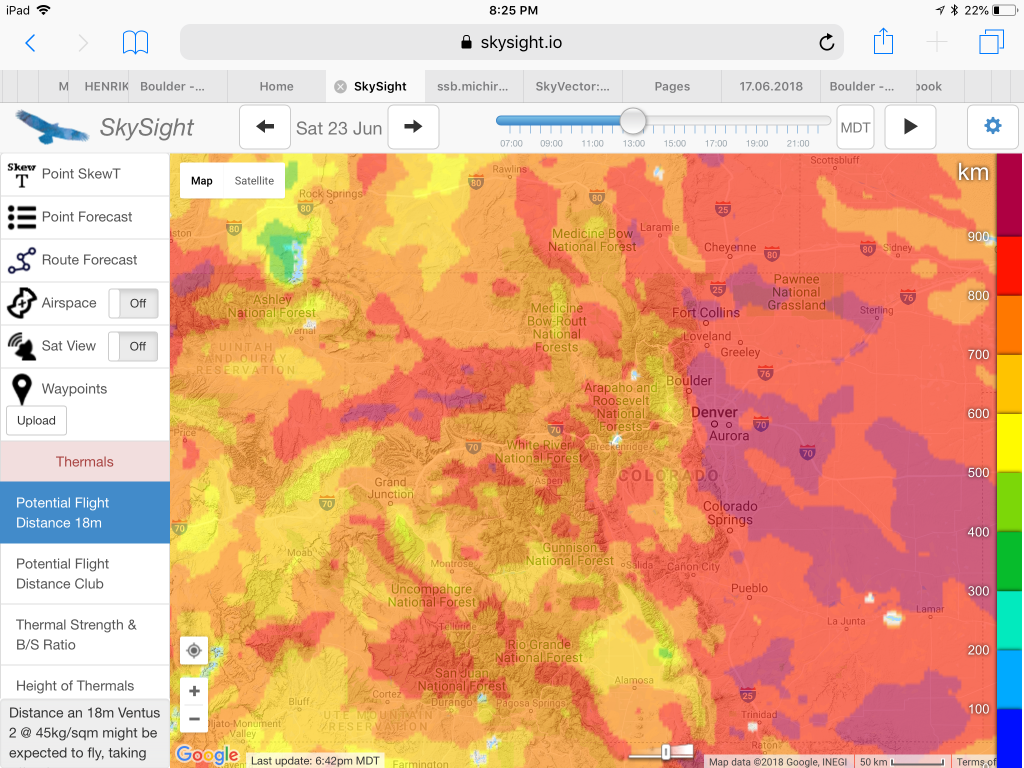

The soaring forecast for this past Saturday suggested strong thermals along the lower foothills but strong westerly winds – and therefore much more difficult conditions – on the west side of the Continental Divide.

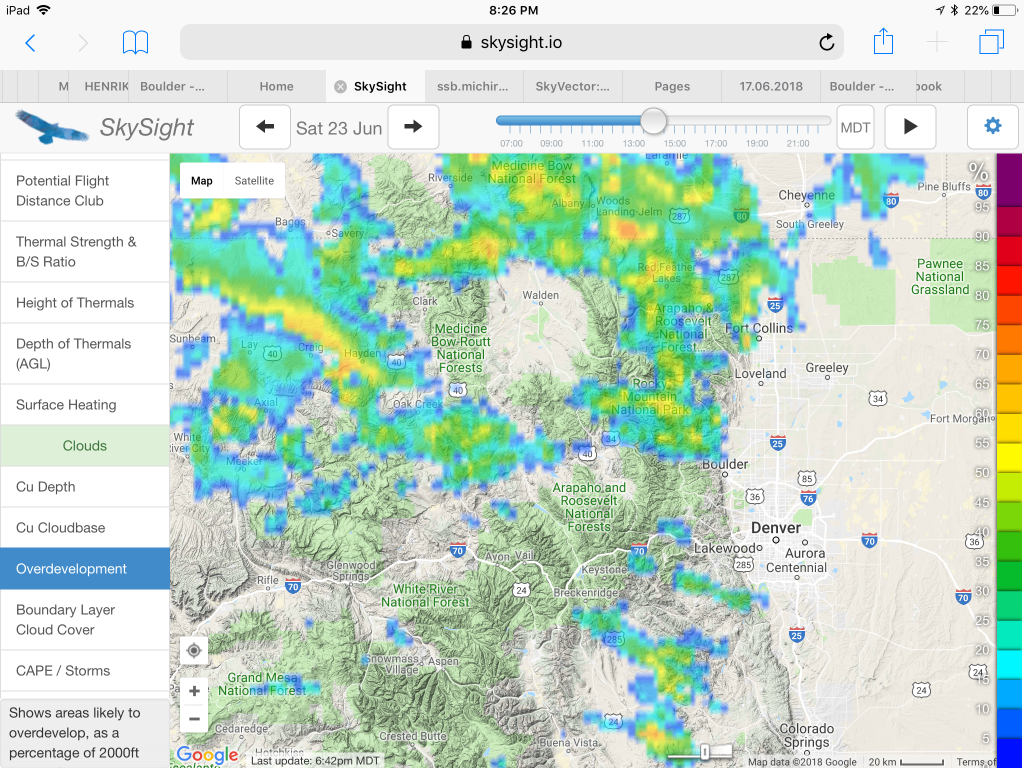

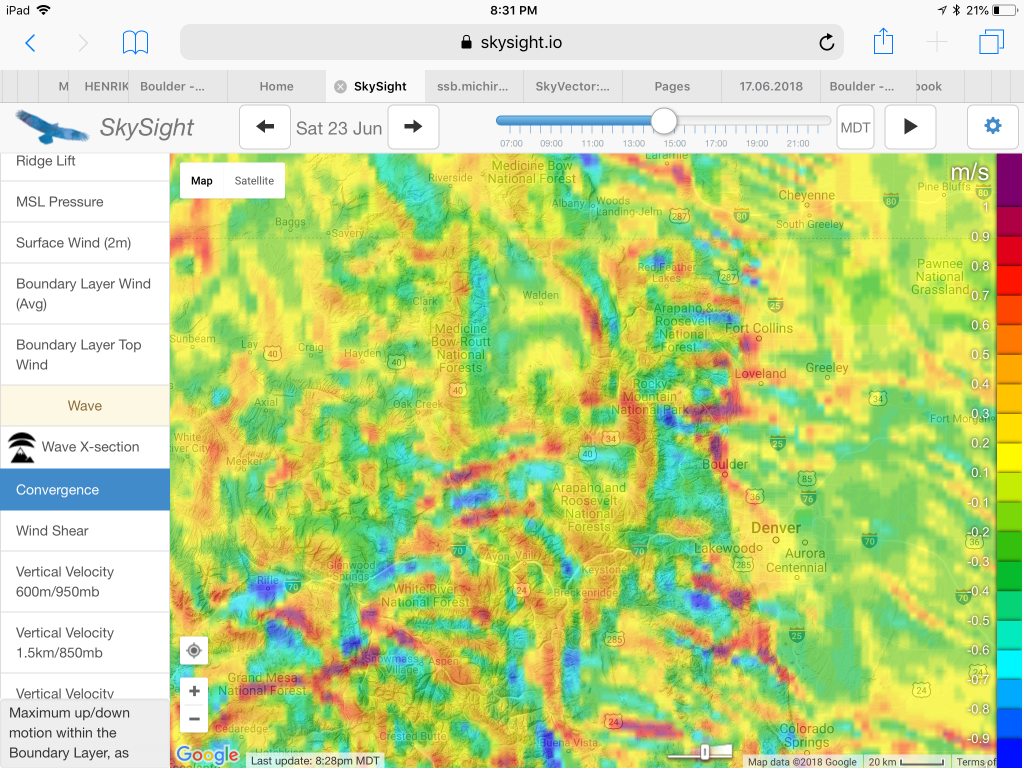

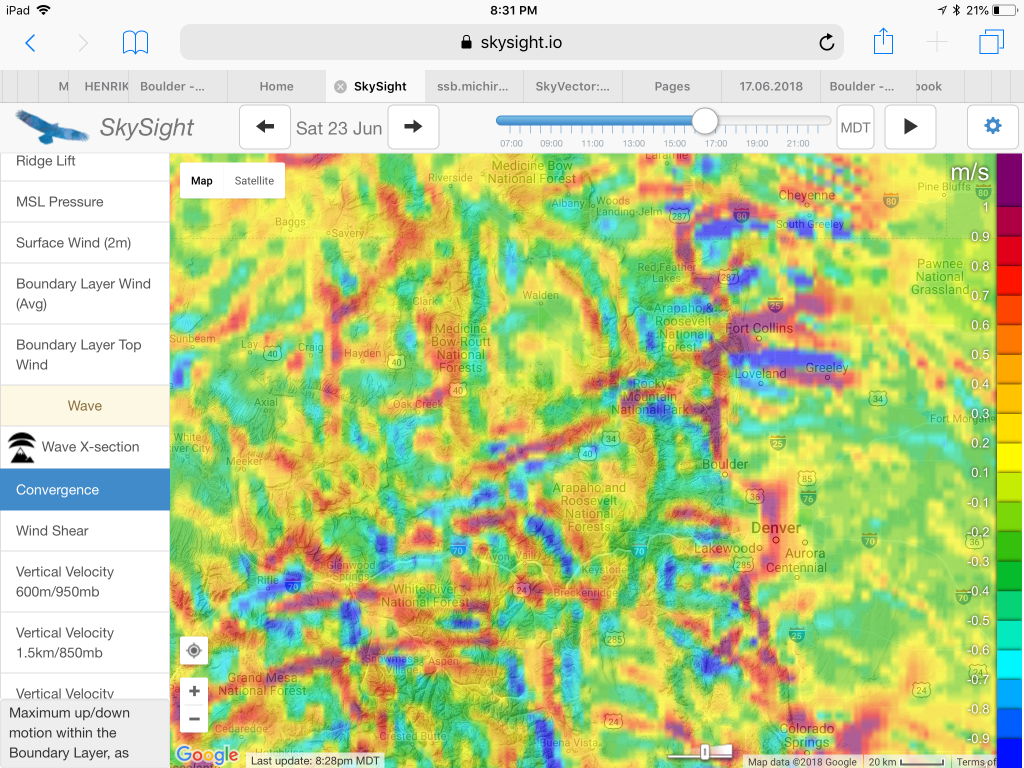

Here are some of the key weather charts that I looked at the night before my flight:

Plus, very important to look at, especially in Boulder, is the convergence forecast.

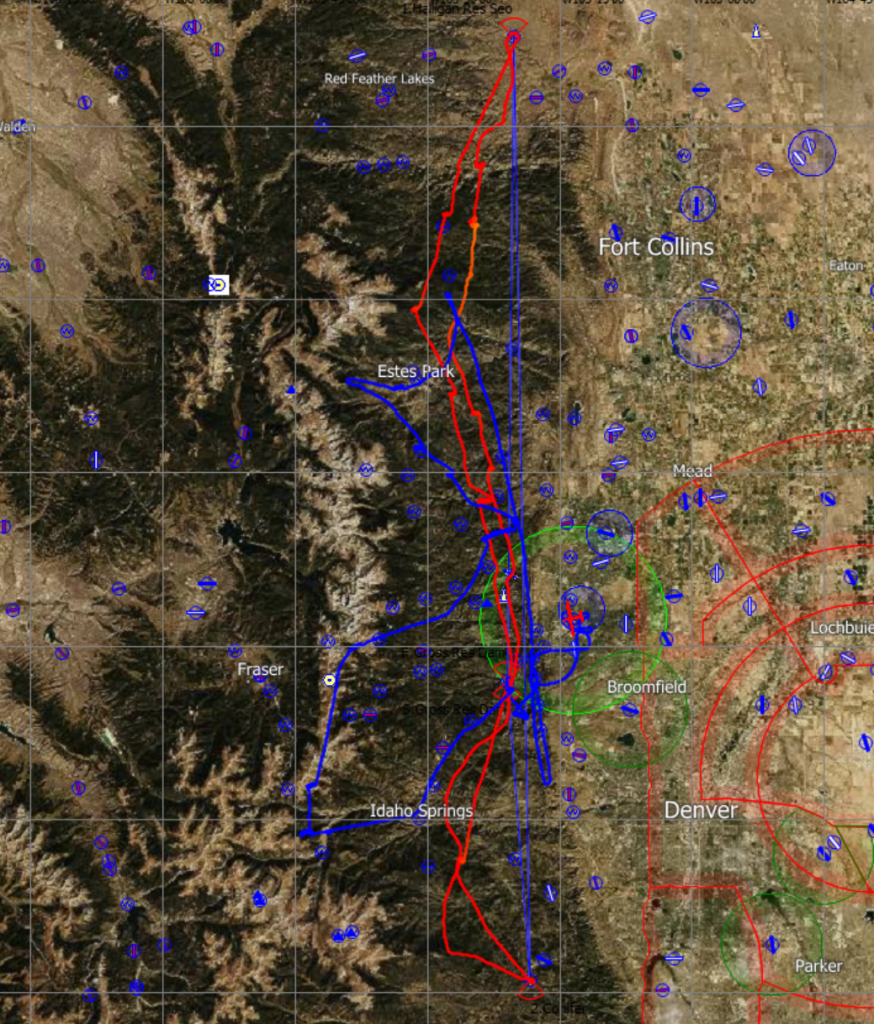

Given these conditions I decided I would stay on the east side of the divide and plan a pre-declared 300km triangle route that would take advantage of the strong thermal conditions along the lower foothills as well as the convergence lines. If the convergence forecast would hold and if I did my planning right, I might even be able to fly relatively fast and get some points for the OLC speed league as well.

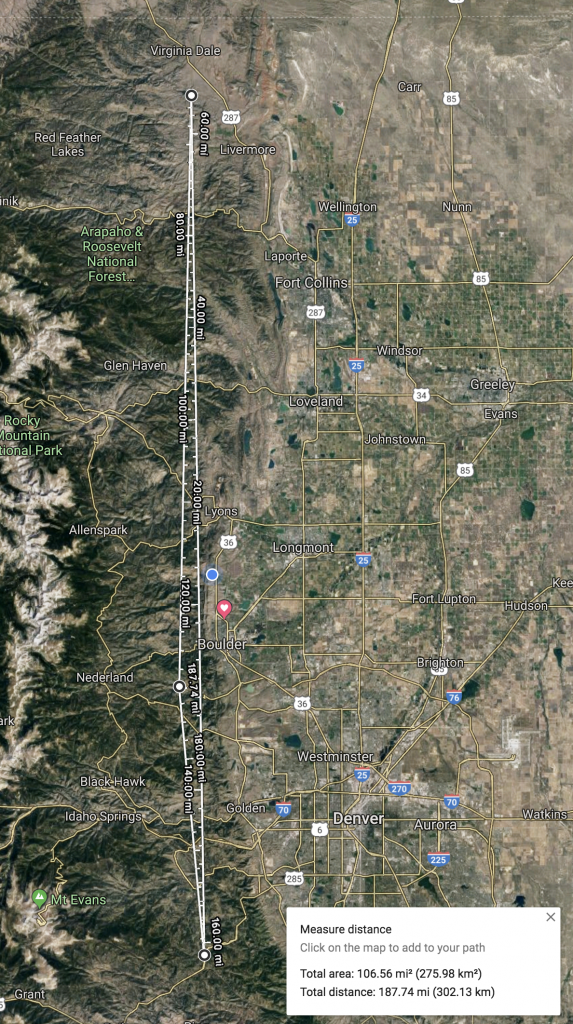

With these objectives in mind, I declared the following triangle that would meet the requirements for a Diamond Goal Flight according to the FAI.

Start at Gross Reservoir Dam. I wanted the start to be within a 15 km radius around the Boulder airport since you have to fly through this cylinder after getting off tow to qualify for OLC speed league points. Gross Reservoir is just within the 15 km mark. It is also on the west side of the Flatirons, where thermals tend to start much sooner than on the east side where the inversion can be very persistent. Another advantage is the fact that the south-tow route from Boulder runs along Eldorado Canyon, just a little south-east of the reservoir. (When towing north, a good alternative start point within the 15 km cylinder would be Bighorn Mountain.)

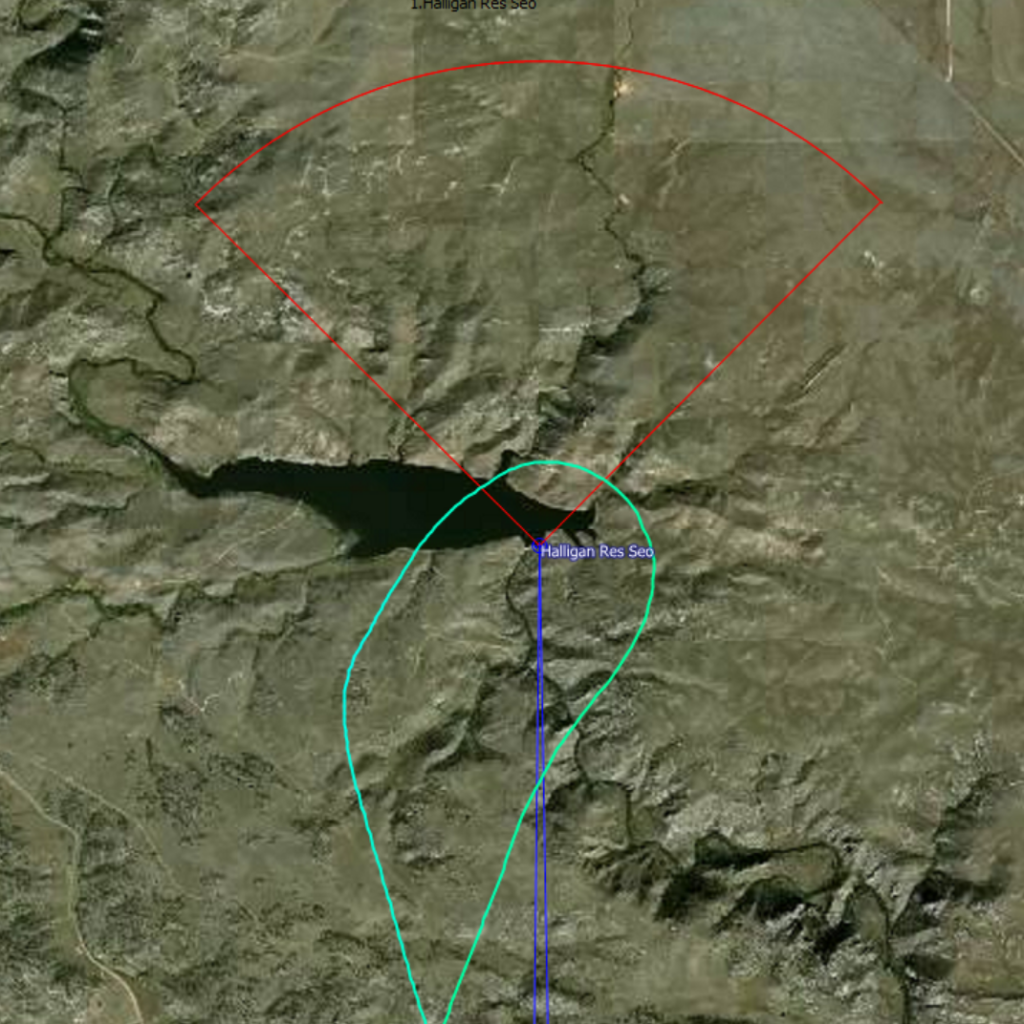

First TP at Halligan Reservoir, 103 km to the north of Gross Reservoir. According to my forecast, the convergence line would likely be a few miles east of Halligan. There were two reasons I wanted to stay on the west side: 1) the lift tends to be much weaker once you get into the more humid air mass that typically lies east of the convergence; and 2) the cloud bases on the east side are often much lower. The last thing I wanted was to be forced to descend down low just to round a turn point and then have to work my way back up. I also considered moving the TP further north but the mountains get lower the closer you get to the Wyoming border and this often means that the prevailing westerly winds tend to be stronger and therefore the thermals weaker and less organized.

Second TP at Conifer, 151 km to the south of Halligan Reservoir. The projected location of the convergence was, once again, among my top reasons to pick Conifer. It also has the advantage of being less than 60 km away from Boulder, which means that given the forecasted height of the cloud base around 18,000 feet, it would be well within final glide range of the Boulder airport. I therefore considered it a stress-free turn point even if the conditions would be less than ideal.

Finish back at Gross Reservoir Dam, 48 km to the north of Conifer, for a total triangle distance of 302 km (164 nautical miles).

I knew, of course, that reality never exactly matches the forecast. To prove this point, as I drove to the airport in the morning, a long and wide lenticular cloud shielded the sun from reaching the ground along the foothills over a stretch of at least 100 miles. The temperature at the airfield was pleasantly cool but this only meant that without direct sunshine, thermal activity would start much later than 10:30AM as projected in the forecast.

However, given that it was June 22 – just one day beyond the summer solstice – there was a lot of daytime left for the lennie to disappear and for the day to develop.

Around 11:30AM the cirrus shield had become noticeably smaller and thinner and the temperature on the ground started to rise quickly. The more impatient pilots decided to launch, unfortunately only to return to the airfield 20-30 minutes later. Clearly, it was still too early. I kept telling myself that there was no reason to rush. Sunset was at 8:34PM and thermal activity would likely last until well past 6PM. And my task should not require more than 4 hours, maybe even considerably less.

I decided to remain on the ground until the first pilot would stay air born. That was the case around 12:30PM. I waited for one more pilot to launch and finally took off just before 1PM.

A beautiful cumulus cloud had formed right above the Flatirons – ideal for a south tow towards my start point. I stayed on tow probably a little longer than necessary and released in the second good lift at just under 10k feet MSL. My climb rate immediately improved once I was off tow – funny how that works – and within minutes I was up at 15k feet and ready to get on task.

There were some nice looking cumuli right along the task line interspersed with some blue gaps in between. The first gap was perhaps the biggest at about 15 miles but I wasn’t bothered by it. I had enough altitude and the cloud ahead looked very promising. I was also within glide range of Boulder and knew that in the worst case I could try again. I also saw some developing wisps along my path and slightly adjusted my route by a few degrees here and there to take advantage of any rising air, always staying slightly on the upwind side.

A very powerful climb near Estes Park (up to 15 kts average!) took me to 17,000 feet and another over Signal Mountain to 17,500. The path forward to my first TP was along the convergence zone: generally the air was just rising up by 1-2 kts and I was able to fly in a straight line while maintaining altitude as long as I wasn’t pushing for speed.

As I got closer to Halligan Reservoir the cloud base dropped a little so I flew a bit faster to come down as well, rounding the turn point at an altitude of 16,000 feet.

Looking back to the south after my 180 turn, I noticed the convergence had continued to develop and the line was now better marked.

West of Ft. Collins I stopped to get back to over 17,000 feet before continuing my convergence surfing: the line wasn’t completely straight so I curved gently along its west side, flying faster in sink and slowing down in lift, for the most part able to avoid any thermaling.

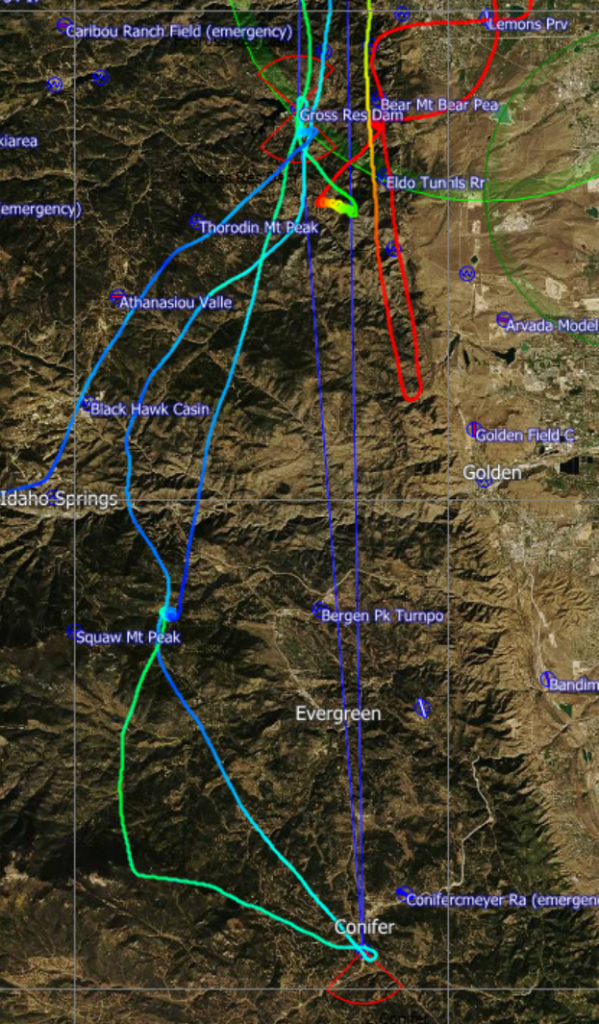

West of Golden, the convergence line made an obvious turn toward the west so I decided to make a little detour as well:

Conifer lay about 10 miles east of the convergence requiring me to temporarily leave the air mass that had carried me so well. Once again I had to drop down to about 16,000 feet to make the turnpoint and stay clear of the clouds.

After rounding Conifer, I headed right back toward the convergence line, following along a ridge towards Mt Evans where the air was slightly ascending which meant I was also to get back to the convergence without losing much altitude. Near Squaw Mountain I stopped in a thermal to top up to 17,700 ft and from there it was a straight glide to the finish line over Gross Reservoir.

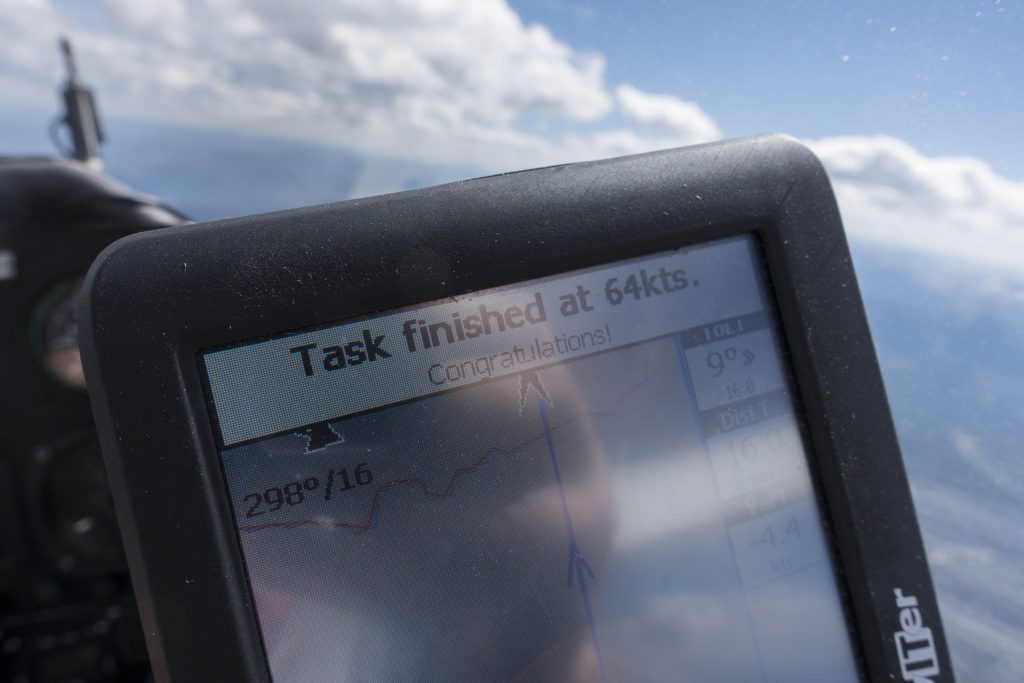

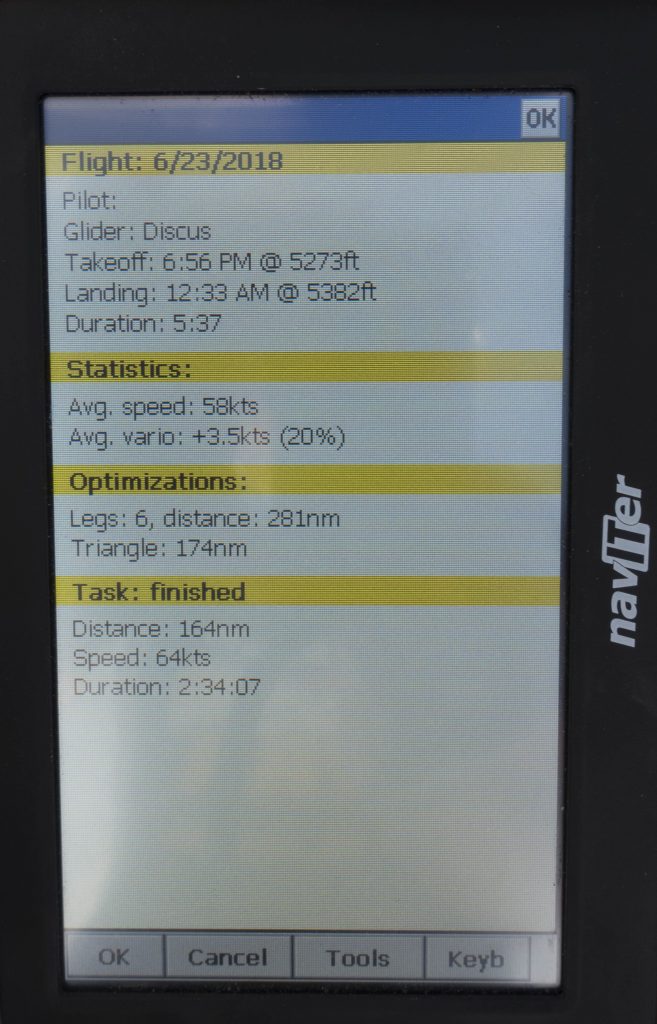

A glance at the flight computer told me I had completed my 302 km task in just 2 hours and 34 minutes. That equated to a respectable average task speed of 118 km per hour. I’m sure an experienced XC pilot could have shaved off another 20-30 minutes but I’m definitely happy with this result for my fist 300 km goal flight. (I even arrived 1000 feet higher than I had started out!)

With my task completed, I wondered what I could add-on to enhance my OLC score. I thought it would be great if I could turn my overall flight track into into a big FAI triangle. To do that I would have to cross the Continental Divide and fly west to a point roughly perpendicular to the line between Halligan Reservoir and Conifer, and approx. in the middle of it. Kremmling, I thought, would be an ideal turnpoint to shoot for. If this worked I might be able to post a 400 km FAI triangle.

The first practical question was how to get to the Divide. The straight line west from Gross Reservoir did not look promising as it meant pushing into a big blue hole against a 15-20kt headwind. There were no clouds for 20 miles and I expected a lot of sink in the lee of the mountains. Quick decision: I would return towards Mt. Evans where the convergence line had already proven to work – then I would fly north along the divide and look for a cloud street that could take me west.

In trying to execute this add-on plan, the first part worked well. Within 20 minutes I was on the divide near Silver Plume Mountain.

As I continued to head north along the ridge I hit significant sink. I stopped at Mt. Flora to get back to 17,500 before a blue gap to the next cloud near Mt. Jasper. There I only found a very weak climb in turbulent conditions.

Unfortunately the clouds to the west of the divide were now rapidly over-developing. As I circled around Mt. Jasper I could see more and more virga and rain showers developing in the direction I wanted to fly in and so I decided to shelf my FAI triangle plan for another day.

Continuing along the divide also seemed pointless as the thermals on the ridge were weak and extremely wind-blown. The convergence over the foothills still looked promising, however, and so I headed back towards Gold Lake. With the wind from behind this was a quick transition but I still lost quite a bit of altitude flying through the lee side sink. I had been right not pushing into the wind earlier.

A mediocre climb near Jamestown (I wondered: would I have taken this had I been trying to get somewhere?) took me back to 17,000 and a vicious rotor over the Twin Sisters (i.e. in the lee of Longs Peak) brought me to 17,500 feet. From there I tried to connect with the clouds on top of Trail Ridge Road to maybe push a little further west from there. However, by now I should have known better than to approach the Divide from the lee side on such a windy day. After hitting heavy sink I scrapped that plan as well and headed back to the tried and true convergence line north of Estes Park. By now overdevelopment set in almost everywhere around me and although the lift was still strong, the lack of sunshine in the cockpit meant I was getting cold.

With 6pm approaching the next decision was simple: enough for the day. I started my final glide north of Estes Park, flew straight to Golden and from there back to Boulder where I arrived with plenty of altitude to spare.

My total flight distance ended up being 523km. My bonus goal of earning OLC Speed League points for our club worked out too. With 118 points I scored second for SSB this past weekend and first among those flying from Boulder. The flight track is here.

Lessons Learned

- Careful task planning can pay off. Usually a pre-declared route should mean a lower average speed than simply following the best visible lines. However, by carefully planning my task in accordance with the thermal and convergence forecast I was able to pre-plan the flight in a way that took advantage of the best projected energy lines. And since the reality was not very far off from the forecast, requiring only a deviation of about 20 miles or so, I was able to complete the task as quickly as I did.

- Flying with a specific goal in mind greatly focuses in-flight decision making. On previous flights when I took off without a specific objective in mind, the choices were endless. This meant I often took a while to make up my mind and I also found myself reversing decisions I had made simply because small changes in the sky momentarily made some other direction look more promising. This Saturday I had a clear goal and all my decision were made to safely get to the goal as fast as possible. The difference this makes to the thought process is amazing. At any given point there are much fewer choices available and I’ve found myself homing in on those choices much faster.

- Flying with a specific goal makes soaring even more fun. Sure, even without a goal it is fun to take advantage of the wind and the sun and enjoy the amazing sight-seeing that can be had high above the Rocky Mountains with all of Colorado spread-out below. However, I’ve found that on days when staying up is super easy the level of fun increases to another level by adding some additional challenge and being able to measure progress against that challenge. Try it out!

- Convergence lines can be the key to flying fast – especially in this area where they are a very frequent phenomenon. Even if the lift along the convergence is only 1-2 kts it basically means you can fly in a straight line (maybe with slight route deviations here and there) without having to stop to thermal. You are much faster overall when floating along at 60 kts IAS at 17,000 feet than to push 80 – 90kts between thermals, then stopping to climb before putting the nose down again.

- Always remember the power of lee side sink. I made the right call when I decided to transition to the divide from Gross Reservoir via an established convergence line towards Mount Evans. Flying there directly into the wind would have likely been impossible. I should have remembered this lesson when I tried it again a bit later over Estes Park. Although the distance to bridge was much shorter flying in heavy lee-side sink against the wind requires a lot of excess altitude.

Bravo well done Clemens!

thanks! all your advice has helped a lot, Al! Still much to learn 🙂

Congratulations on a terrific flight and a wonderful write-up! Thank you!

Marc Arnold

thanks, Marc!

How could you complete Diamond Distance on that flight? This has to be done around pre-declared turn points as well as far as I know 😉

Albert – “The FAI Diamond Badge involves 3 required elements. Diamond Altitude is a 5,000-meter (16,404-foot) altitude gain above an in-flight low point; Diamond Goal is a 300-km (186.42-mile) cross country flight using a pre-declared Out and Return or Triangle course; Diamond Distance is a 500-km (310.7-mile) cross country flight.” So my reading is that the 300 km must be pre-declared (which it was) and the 500 km does not require pre-declaration.

Albert – I stand corrected. I’ve been advised by the SSA that Diamond Distance must be indeed around pre-declared turn-points (unless it is a straight distance flight from the release or a start point). I’m assuming that this is to be inferred from the following list of definitions of Soaring Performance Types, which suggest that a distance task can only be a straight distance flight without TP or a pre-declared distance flight from start to finish with up to 3 turn-points. The (arguably unnecessarily complex) definitions are below:

SC3 1.4.2 – SOARING PERFORMANCE TYPES

a. GAIN OF HEIGHT A SOARING PERFORMANCE conducted per 1.3.5 for a given

badge (see 2.2.1c, 2.2.2c and 2.2.3c) or a record (see 3.1.7a).

d. STRAIGHT DISTANCE A COURSE without TURN POINTS starting from RELEASE or a

declared START POINT.

e. GOAL DISTANCE A COURSE without TURN POINTS, from a declared START

POINT to a declared FINISH POINT.

f. 3 TURN POINT DIST. A COURSE from the RELEASE POINT or a declared START

POINT to any type of FINISH POINT, using one to three declared

TURN POINTS in any order.

g. OUT & RETURN A CLOSED COURSE with only one declared TURN POINT.

h. TRIANGLE A CLOSED COURSE via 2 or 3 declared TURN POINTS flown in

the sequence declared. When 3 TURN POINTS are used, the

COURSE distance is the sum of the legs between the TURN

POINTS.