The best soaring routes almost always correspond in one way or another to the terrain below, no matter what lift you use.

E.g., you would expect thermal lift over terrain that is most exposed to the sun (e.g. slopes that are most directly warmed by the sun based on the time of day); you would expect convergence lift where terrain features redirect the wind such that air masses collide with one another and are forced upwards; and you would expect ridge lift along long and steep slopes that are more or less perpendicular to the direction of the wind. (It’s no surprise that pilots love to fly along the top of ridge lines where thermal, ridge, and convergence lift often come together.)

It’s no different with wave lift. Wave lift forms when the wind pushes (relatively stable) air downward along the lee slope of a mountain, thereby warming it at the dry adiabatic lapse rate (such that it becomes warmer than the surrounding air near the ground). It will then rise again because it became lighter than the surrounding air mass, thereby starting a wave motion that oscillates on the back side of the mountain. (You can find more details about wave lift here.)

Wave lift will form only if the wind is relatively strong. In most locations, such strong winds usually come from the same direction. In Boulder that is from the west – especially in the wintertime when the jet stream blows at our latitudes. What makes Boulder a particularly great wave location is the fact that a tall, nearby, mountain range – the Colorado Front Range – is conveniently laid out in north-south direction (hence the prevailing wind has to cross it at a perpendicular angle) and the Boulder airport is just to the east in the lee of the mountains.

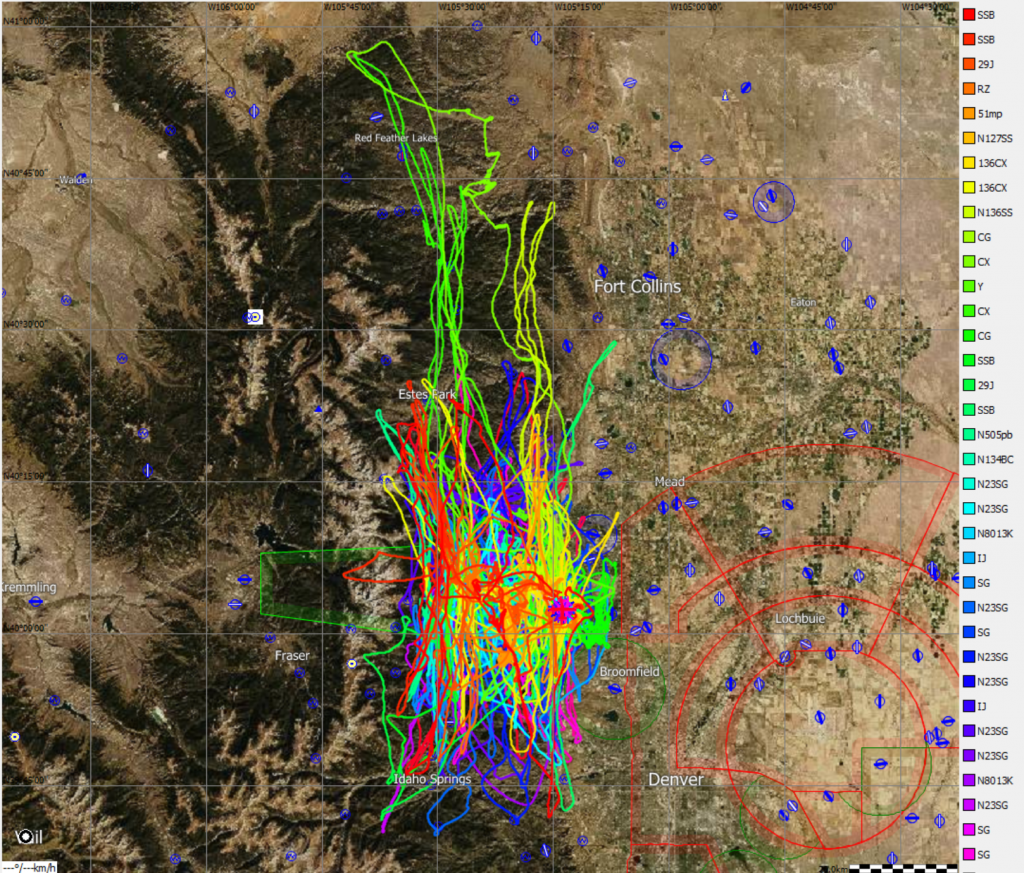

With all that said, it should be no surprise to see that wave flights from Boulder tend to follow the same routes: parallel to the mountains on the lee side. In fact, the following chart depicts 40 wave flights from Boulder from 2010 and 2017 that were longer than 2 hours in duration and extended above 17,000 feet.

If you study the flight logs a bit, you quickly notice that the traces tend to be parallel to the curving ridge line. The distance of each trace to the mountains depends on two things: (1) the wave length on the particular day (it can be longer or shorter depending on the strength of the wind and the stability profile of the air); and (2) in which wave bar the pilot was flying (e.g. the primary, secondary, or tertiary wave). The primary wave is the one closest to the mountains; it usually (though not always) provides the strongest and highest lift. As the name implies, the secondary is the second wave bar behind the mountains, the tertiary the third, and so forth.

Take a look at the red trace that extends furthest to the west – it is the only one in this set that crosses the Continental Divide. This flight was flown by Al Ossorio on Dec 29, 2010 in the club’s DG505 and reached more than 27,000 feet within the designated wave window (Arapaho Peaks Soaring Area). However, note that the high point was not over the Continental Divide; it was several miles further east, just where the red trace blends with all the other traces – the typical location of the primary wave.

Also quite interesting are the two greenish traces that extend furthest to the north. Both were flown much more recently by Bob Faris on two subsequent days in December 2017 (Dec 1 and and Dec 2) in his DG800. Both flights reached altitudes of just under 18,000 feet. During the more yellowish of the two, Bob got above 17,000 feet only on the outbound leg (following a fairly straight line parallel to the mountains). He then lost the wave near the Wyoming border and had to fly the return leg at much lower altitudes between 9,000 and 12,000 feet mostly in thermal lift (a very warm day in December!). During the more greenish of the two traces, Bob stayed in wave above 16,000 feet almost the entire time and actually flew back and forth along the mountains three times, covering 617 kilometers at the remarkable average speed of 174 kph (108 mph).