Preface: I wrote the article below in January of 2018 and I have since done more detailed research about the same question. My most recent effort uses slightly different (and probably more reliable data) but the overall conclusion remains valid. If you’re interested in seeing the results of my most recent research that also considers the relative risks of other air sports such as General Aviation, Hang Gliding, Paragliding, and Skydiving, you can find it here.

The tragic death of Tomas Reich during the last day of the most recent Sailplane Grand Prix final in Santiago de Chile and the ensuing debate about the safety in soaring competitions brought – once again – a key question to the forefront of my mind: How Dangerous is Soaring Really?

When I started soaring in 1983 at the age of 16, I often heard people say that “the most dangerous aspect of gliding is the drive to the airport”. Intuitively this never felt right to me and several people have since pointed out that it is indeed far from the truth. (See, e.g., the speech Safety Comes First, delivered by Bruno Gantenbrink).

But just how dangerous is it? To get a better sense we need a reference point. I believe the best way to think about the dangers of soaring is to compare it to the dangers of other relatively dangerous activities we might indulge in: e.g. we could go on a road trip, ride a bike, or ride a motorcycle. And I think the best way to make such a comparison is on the basis of participation hours (rather than on the basis of miles traveled for example). E.g., when we have an afternoon to spend we may want to know: is it more dangerous to spend that time riding our bike or to go fly our glider? We have all seen the white-painted “ghost bikes” on the side of the road marking the spots where a cyclist was killed but we haven’t seen any “ghost gliders”. However, we would be kidding ourselves if we thought that gliding was somehow less dangerous. (Spoiler Alert: the comparison is not even close.)

Unfortunately, good, global statistics about the dangers of soaring are hard to come by. In most countries, a comprehensive and reliable database of gliding accidents does not exist. Nor is there a reliable global record of the number of flights or hours flown that would provide a good reference point.

However, while the available data is not globally comprehensive, there is enough out there to draw these comparisons – at least directionally.

My analysis of gliding accidents is based on data from Germany: the German government keeps meticulous track of all flights and even separates out glider flights and flights in motor gliders. It also maintains a database of all flight accidents and reports on an annual basis the the number of fatalities, and the number of persons injured. Now, one might think that using German data is rather limiting. But that is not quite true because gliding is much more popular in Germany than elsewhere. In fact, according to a report presented to the International Gliding Commission in 2010, Germany accounts for approx. one third of all glider flights worldwide. If there is a limitation to using German data, it might be that it actually underestimates the dangers of soaring elsewhere simply because Germany has such a particularly well developed soaring and safety culture. But, since I can’t prove that, let’s assume the German stats do a fair job of representing the dangers of soaring in general.

So here is what I found. The result is – unfortunately – rather sobering.

On average, soaring pilots have an accident every 10,000 flights (this is based on all flights in Germany from 2002 through 2016 – the exact number is 10,070). Fortunately some of these accidents only damage the glider or some other property. But once every 60,000 flights someone (usually the pilot and/or passenger) is seriously injured, and once in 83,000 flights the pilot and/or passenger dies.

If you consider that the average glider flight takes about 38 minutes (arguably my least generalizable assumptions since it is simply based on the flightlog of all club flights of members at the Soaring Club in Boulder between 2002 and 2017) this means that soaring pilots can expect to get seriously injured every 40,000 hours and die every 50,000 hours.

Wow! Fortunately we do also other things in life because these stats mean that we would die every 6 years if we did nothing else but fly gliders!

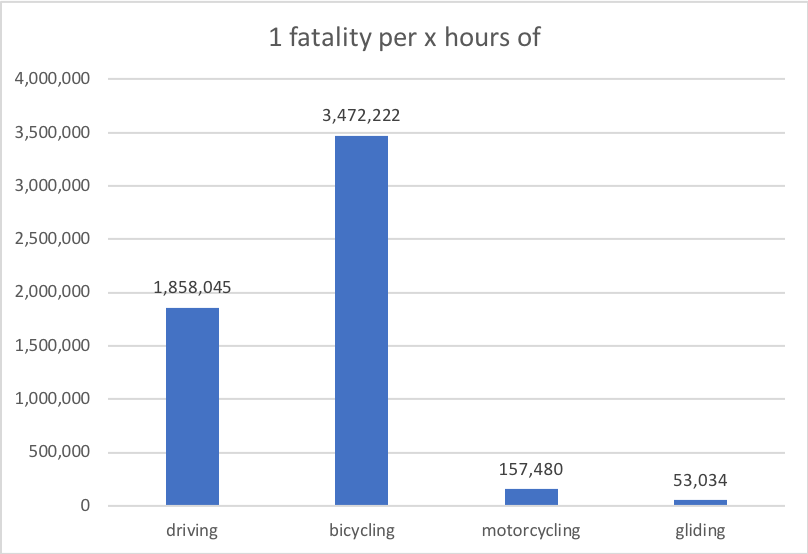

So how does this compare to other activities? Well, not favorably to say the least. On a “per hour” basis, gliding is about 35x more dangerous than driving; 70x more dangerous than riding a bike, and still 3x more dangerous than riding a motorcycle.

Another way to look at this is to say that 1 hour of gliding is about as dangerous as going on a 35 hour road trip in a car, e.g. from Denver to San Francisco and back again. Or as dangerous as riding a bicycle from Denver all the way to Minneapolis (70 hours). Or as dangerous as riding a motorcycle from Boulder to Salida (3 hours).

Is this an acceptable risk to take? I think that is a question we all have to answer for ourselves. But the important thing is that we should all ask that question and think hard about what we can do to minimize the risk in our own flying decisions. And no one should kid themselves into believing that those stats don’t apply to them because they are simply a better pilot. (Instead, they should remind themselves that it’s often the best pilots, like Tomas Reich, who make up the sad statistic.)

With sincere condolences to the family and friends of Tomas Reich.

Thank you for this analyisis. Important to us all.

I’m a hang glider pilot considering a couple of total knee replacements, TKR. Concerned about the risks I googled, fatality rate for TKR. The answer was 1 in 1000. I was appalled. I the googled, fatality rate for hang gliding. The answer was 1 in 1000. For some reason I feel better about the TKR risks. Should I?

It’s worth considering that the hang gliding mortality rate is an annual figure while the TKR mortality is per procedure. You’re only doing a TKR once, hopefully. I would also think that the risk of a TKR is not the same for every one and it might be useful to determine if your risk is likely higher or lower than the median. Whatever you decide, I wish you good luck!