Faster. Farther. Smarter. Most of us want to become better and safer glider pilots. But how? I made it a practice to set specific goals for the coming year so I can monitor and track my progress. As the year draws to a close it’s now time to review how I did against the Soaring Goals I had set myself for 2021. There’s a lot of ground to cover, literally and metaphorically.

Goal #1: Stay Safe

… by always heeding my own advice.

Progress against this goal is hard to measure. But the goal is essential and success is a pre-requisite for anything else. So here’s my assessment. I was 291 hours in the air and flew a total cross-country distance of more than 26,540 km without accidents or incidents so I suppose this has to count for something. I also can’t recall any seriously scary moments. There were definitely a few sketchy situations, e.g. during this flight in Nephi at 58:30, and also during this flight at 11:30. However, I don’t think that I was ever in a truly dangerous spot without a realistic and safe Plan B. At the contests in Montague and Nephi there were two or three instances were other gliders got closer than I would have liked. I have a lot of respect for big gaggles and don’t really like them. However, I can’t recall any real near misses, hazardous takeoffs, or precarious landings. On several occasions, I got close to my personal limits (e.g. during this flight at 3:50 and 25:00, and 44:03) but I never crossed my own red line. Going forward it will be important to stick to my margins and not let them erode.

The following video shows a flight over the desert in highly dynamic weather conditions during the 18m Nationals in Nephi, UT. It was one of those flights where a lot of judgement is required to stay out of trouble.

2. Improve Specific Flying Skills

In particular: improve netto in cruise, use more of the available altitude band, and work on precision thermalling skills.

In 2021 I participated in the 18m U.S. Nationals Soaring Contest in Nephi. This means I now have some great data to benchmark myself again. Compared to the very best U.S. pilots I still have a lot of room for improvement in all these areas. The following data are based on a detailed analysis of all eight contest days. They only include data from pilots who finished each race, hence the average is inherently skewed towards the best pilots. (Note: I performed this analysis with the help of the excellent tool IGC Spy. I uploaded all contest flights to IGC Spy and then copied data from IGC Spy into a spreadsheet for more detailed analysis.)

-

- Netto in cruise. My netto values were better than those of the average contest finisher on only two of the six contest days and worse on the other six days. In aggregate across all eight contest days, my netto value in cruise was 0.2 kts worse than that of the median score among all contest finishers. 0.2 kts doesn’t sound like much but when you fly straight 90% of the time, it is equivalent to underperforming in climbs by almost 2 kts. When conditions are strong, netto is the single biggest contributor to a race outcome. I believe that the following elements contributed to my relative underperformance.

-

- (1) In Nephi I flew often too far on the upwind side of the clouds when it would have been better to stay directly below the darkest parts of the clouds.

- (2) I did not always correctly observe and judge which lines of clouds were developing and which ones were dissolving. I produced a detailed race analysis video of the fastest race day of the Nephi contest where this is most directly visible.

-

- Netto in cruise. My netto values were better than those of the average contest finisher on only two of the six contest days and worse on the other six days. In aggregate across all eight contest days, my netto value in cruise was 0.2 kts worse than that of the median score among all contest finishers. 0.2 kts doesn’t sound like much but when you fly straight 90% of the time, it is equivalent to underperforming in climbs by almost 2 kts. When conditions are strong, netto is the single biggest contributor to a race outcome. I believe that the following elements contributed to my relative underperformance.

-

- Altitude Band. I am biased towards flying high because it has multiple important advantages. TAS > IAS at altitude, and more altitude also means more choices because of a greater glide range. However, staying high also comes at a cost. It means I am less picky in thermal selection and I have to center more thermals. The letter tends to result in sub-par average climb performance. I know of this bias and I am working to reduce it. At the Nephi contest my average height gains in thermals were less than those of the median finisher on six contest days and greater on only two contest days. The average difference per day was less than 200 ft per climb. This isn’t all that much when cloud bases are consistently more than 10,000 ft AGL but it still results in me taking more thermals than necessary.

-

- Precision Thermaling. Next to netto, the average climb rate is the most important factor in competitive performance. It is itself affected by many different components. E.g., thermal selection; speed of centering; ability to remain centered throughout each climb; flying speed while orbiting; bank angle while orbiting; difference in precision for left turns vs right turns, etc. The data from Nephi show that I have a ways to go. My climb rates were worse than that of the median day finisher on six contest days, better on only one contest day, and at parity on one contest day. Across all contest days my climb rate was 0.5 kts worse than that of the median finisher. This is a big gap to close! I identified a few key opportunities for improvement:

-

- Inconsistent and too high thermalling speeds. Remarkably, my orbiting speeds varied widely from contest day to contest day. On a few contest days they were far too high. Interestingly, bank angles don’t appear to be a big issue for me – in fact, my orbiting times were slightly shorter than those of other competitors despite my higher orbiting speeds – this implies tighter bank angles than average. I.o.w., reducing my thermalling speeds while maintaining bank angles should reduce my orbit times to about 25 seconds which is appropriately tight when flying with full water ballast.

- Inconsistent loss percentage. On most days my altitude lost in thermals relative to the altitude gained was quite low and competitive: in the range of 3%-7%. However, on two contest days my loss percentage was greater than 10%. Compared to the average of all finishers my loss percentage was worse on six out of eight contest days.

- Thermal selection. On some days I was more tempted than other competitors to accept sub-par thermals. This is likely a confidence issue that will improve with experience but it is something to be aware of and monitor.

- Other factors played smaller roles. On average I performed better in right turns than in left turns but this was not consistent for all contest days. My loss percentage in thermals was noticeably greater in left turns than in right turns. There was no significant difference in flying speed and orbiting times between left and right turns.

-

- Precision Thermaling. Next to netto, the average climb rate is the most important factor in competitive performance. It is itself affected by many different components. E.g., thermal selection; speed of centering; ability to remain centered throughout each climb; flying speed while orbiting; bank angle while orbiting; difference in precision for left turns vs right turns, etc. The data from Nephi show that I have a ways to go. My climb rates were worse than that of the median day finisher on six contest days, better on only one contest day, and at parity on one contest day. Across all contest days my climb rate was 0.5 kts worse than that of the median finisher. This is a big gap to close! I identified a few key opportunities for improvement:

The analysis above benchmarks my performance against the median finisher of each contest day. The magnitude of the improvement opportunity is of course even greater. It can be shown by using each day’s winner as the benchmark instead!

The following video shows a highly detailed race analysis of the 7th race day during the 18m Nationals in Nephi. I learned a lot just from creating this video.

Goal #3 – Speed Goals

I had no contest experience prior to 2021 so my speed goals were focused on local objectives flying from Boulder.

-

- When flying on Speed League Weekends my goal was to score among the top 3 Boulder pilots 66% of the time (up from 50% in 2020). There were 15 Speed League Weekends in 2021. I was able to fly on 8 of them. The other ones were either unflyable or I was travelling to or from a contest and unable to participate. I finished among the top 3 Boulder pilots on six out of these eight weekends, i.e. 75% of the time. This means I exceeded my goal of 66%. (Twice I finished first, three times second and one time I finished third. Once I finished 4th out of 11 participants, and once I decided to cut my flight short due to thunderstorms and finished 6th out of 7 participants.)

- One of my stretch goals for the year was to break one of the Open Class Colorado Speed Records. I made a few attempts but each was ultimately unsuccessful.

The following video shows one of my attempts to break the 500km Out and Back Colorado State Speed Record. I got very close but ultimately failed due to two major mistakes.

Goal #4 – Distance Goals

For 2021 I defined a portfolio of distance objectives and set myself the goal to achieve at least two of them. Here’s how I did:

-

- I added another state reached from Boulder to my list with a flight to Nebraska.

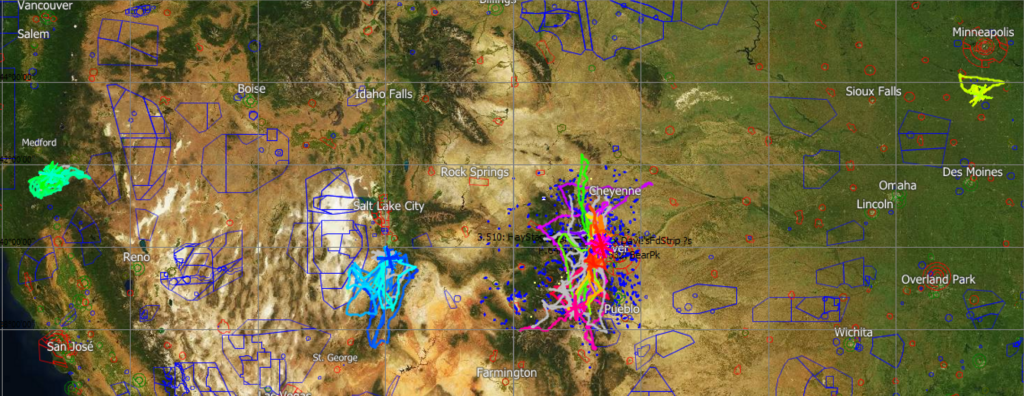

- I completed not just one but two >1000 km flights per OLC plus rules. They were on two consecutive soaring days in August and were the longest flights by any pilot flying from Boulder during the entire year, which is particularly gratifying. One was the same as the Nebraska flight, the other one is here.

- I also completed a declared >750km FAI triangle. TP 1 was south of Salida, TP 2 at Yampa Valley Airport, and TP3 at near Cheyenne, Wyoming. This was also my second 750 km Diplome flight. In addition, the flight qualified as an Open Class Colorado State Soaring Record for Distance Up to Three TurnPoints with a distance of 468.7 miles (754 km).

- I also added eight additional peaks to my Colorado 14er bag. Both flights were out of Salida. On Sep 13 I reached all the 14ers in the Blanca Massif (part of the Sangre de Cristo Range), and on Sep 14 I added four peaks in the northern San Juan Mountains (Uncompahgre Peak, Mt. Sneffels, Wetterhorn Peak, and San Louis Peak). That leaves another 11 peaks to complete the 14er challenge of flying over all 58 Colorado mountains higher than 14,000 feet.

The following video is a short and fun summary of one of my 14er flights from Salida along the Sangre de Cristo Range to the Blanca Massif.

Goal #5 – Contest Goals

I didn’t have a lot of specific objectives other than to compete in my first contests. My plan was to fly in three contests, a goal that I accomplished.

-

- At the Region 7 contest in Albert Lea, MN we only had one valid flying day as the rest of the week was completely rained out. I thought this meant no official result but the SSA still sent me a nice medal confirming my 2nd place contest result.

- At the 20m 2-seater Nationals in Montague, CA, I flew with my friend Bill Kaewert in his beautiful AS32 Mi. We finished the contest in fourth place out of eight contestants – a very respectable result. This also accomplished my stretch goal of finishing in the top 50% of a National Contest.

- At the 18m Nationals in Nephi, UT, I finished 22nd out of 34 contestants. This was about as good as I could have hoped against a field that included a large proportion of the best US contest pilots. Several former national champions finished behind me.

Here’s another video from one of my contest flights in Nephi. This one depicts an ultra-fast final glide that caused me to come home well below minimum time – not a great way to achieve an optimal score!

Goal #6 – Giving Back

I continued to commit a lot of time and effort towards inspiring others worldwide to join our sport, to develop, excel, and stay safe. I did this through:

-

- Writing on ChessInTheAir.com and Facebook; I also wrote a title feature article for the the August edition of Soaring Magazine about the Nephi Contest.

- Numerous soaring presentations including:

-

- Declared Tasks and Badges – a practical guide especially for newcomers to cross-country soaring

- Launch to Soar: How to Get Up and Connect with the Good Lift – this is an essential guide for anyone flying from Boulder who wishes to make the most of the exceptional soaring conditions along the Colorado Front Range.

- Soaring Accidents: How not to Become a Statistic – soaring is a dangerous sport and mistakes can be very costly. Fortunately, most mistakes have already been invented. Which means we can and must learn them!

-

- Numerous Podcast contributions in Soaring the Sky and The Thermal.

- Carefully produced soaring videos on my YouTube Channel Chess In The Air. Among my favorite videos of 2021 are:

-

- Detailed Race Analysis from the fastest Race Day in Nephi – this was probably the fastest soaring race in thermal conditions in soaring history – it provides detailed lessons on how to fly faster;

- Thermals, Rotor, Wave, and Convergence in One Single Flight – a nice illustration of most of the forms of lift that glider pilots use to fly long distances; and

- Scary Final Glide: Glider Flies Through Thunderstorm – it took me 18 months to collect the courage to publish a video from this flight. It gives detailed insight into the decision making process when confronted with very challenging conditions ahead.

-

- Throughout 2021 I have also been serving as president of the Soaring Society of Boulder, one of the largest and most successful soaring clubs in the United States.

So, that’s it for now. Next up will be my soaring goals for 2022.

From the section “Too high thermalling speeds” it’s interesting that you conclude your bank angle is steeper than average. I suspect a compromise of the wide angle lens is it distorts the viewers’ perception of bank angle. Sometimes it’s difficult to read the airspeed gauge and I had the impression your bank angle was relatively shallow until reading this conclusion. I’ll recalibrate my eyes the next time I watch you vids.

It’s no joke when you’re getting bounced around down low trying to make appropriate go/no-go calls. From the noise in the cockpit and your commentary one gets only a vague sense of the turbulence but generally the fixed camera mount and/or image stabilization does a good job. Unfortunately this downplays what you’re really being subjected to and I long for a little shake like you sometimes see in action movies to “keep it real”.

Congratulations on a safe and most impressive season! Your analyses are fantastic and above approach to improving is spot on. Looking forward to seeing further improvements in 2022.

Hi Tayler, thanks.

I upload my flights to WeGlide as well as to OLC. One of WeGlide’s advantages is that they have a stats section that shows your bank angle for each entire flight and also for each of the segments. The width of the thermals varies. In Boulder conditions 40-45 degrees seems to work best on most days.

For folks flying Schempp-Hirth gliders there is a simple visual reference right in the cockpit: the sides of the instrument panel are angled at 45 degrees. So if one of these sides is parallel to the horizon, you’re flying at a 45 degree bank angle.

Congrats on a very succesful and safe season Clemens!

I especially love goal #6, thinking consciously about how to give back to the community is a great thing. I think sometimes pilots get so focused on their own competitive goals, they forget that there are many ways to give back and grow the soaring community.

You don’t have to become a volunteer inspector, club board member or instructor to give back, especially in this digital age there are several avenues to inspire others.