When the days get shorter, the air is cold,

Thermals die down: circling gets old;

When the North Pole turns dark, the jet stream south shifts,

The wind picks up: down the mountain it swifts;

When rotor clouds and lennies appear,

It means only one thing: wave season is here.

With my first wave season in Boulder upon me, I spent some time studying what I could find about the local conditions at my new soaring site in Boulder, Colorado.

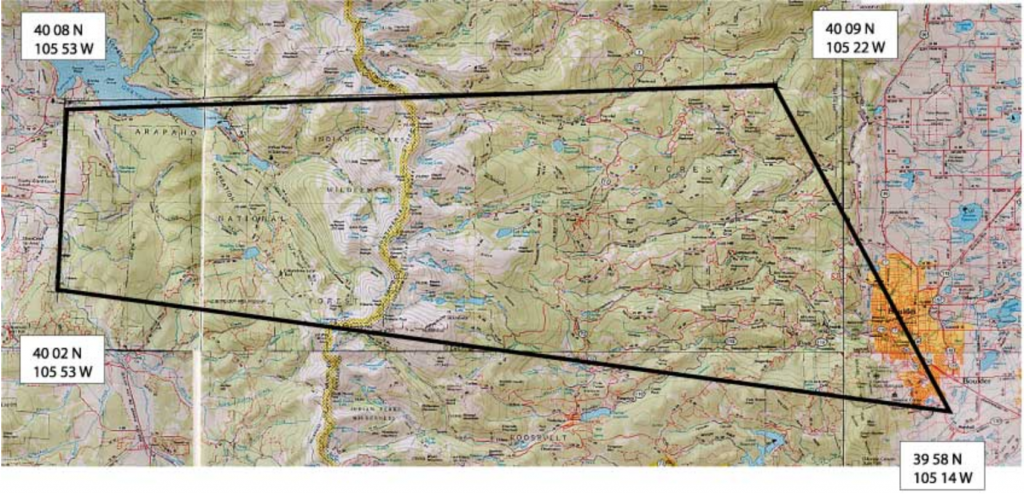

- Boulder Topography

Boulder lies directly at the foot of the Northern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains: a ~100 mile long mountain range laid out in N-S direction extending roughly from the Wyoming border in the North to Mt Evans in the South. Boulder is about in the middle and just East of the range, approx. 20 miles from Mt Arapahoe in the Indian Peaks Wilderness.

The local soaring club, the Soaring Society of Boulder, has negotiated a good-sized wave window, which allows for flights in Class A airspace above 18,000 feet, after “opening” the window with air traffic control in Denver. John Seaborn created an airspace file in Tim Newport-Peace format that you can download here to install on your flight computer (it’ll work with XCSoar). If you have an Oudie, you need a file in OpenAir format. I could not fine one, so I created one myself using the coordinates below. You can download it here. If you need instructions on how to install it, I found the following page from Williams Soaring to be most helpful (it obviously deals with a different wave soaring area but the installation methodology is the same.)

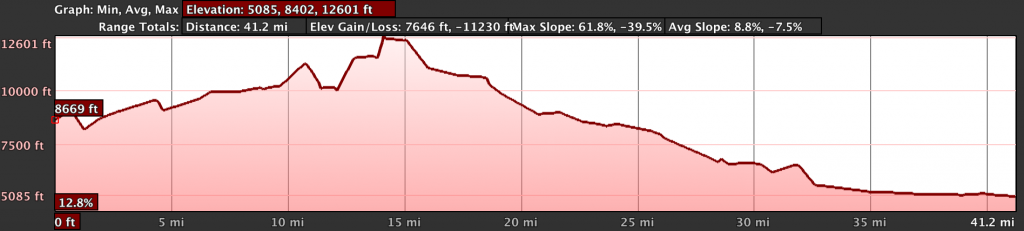

After an initial steep ~2000 ft drop on the lee side of the Continental Divide (which triggers the wave in strong westerly winds if the stability profile of the air is favorable), the terrain slopes more gradually towards the plains. The gradient is steep enough that on fair weather days it is normally possible to reach the airport with any of the higher performance planes. That is not true in wave, however, as sink rates of 2,000 ft per minute or more can put the glider on the ground very quickly, even when flying with a tailwind. The terrain over the foothills is also basically unlandable. It is therefore paramount to stay high when flying over the hills.

Wave flights are obviously not restricted to the wave area – outside the window they just have to remain below 18,000 feet. A summary of the local procedures is here.

- Recognizing Wave Conditions in Boulder

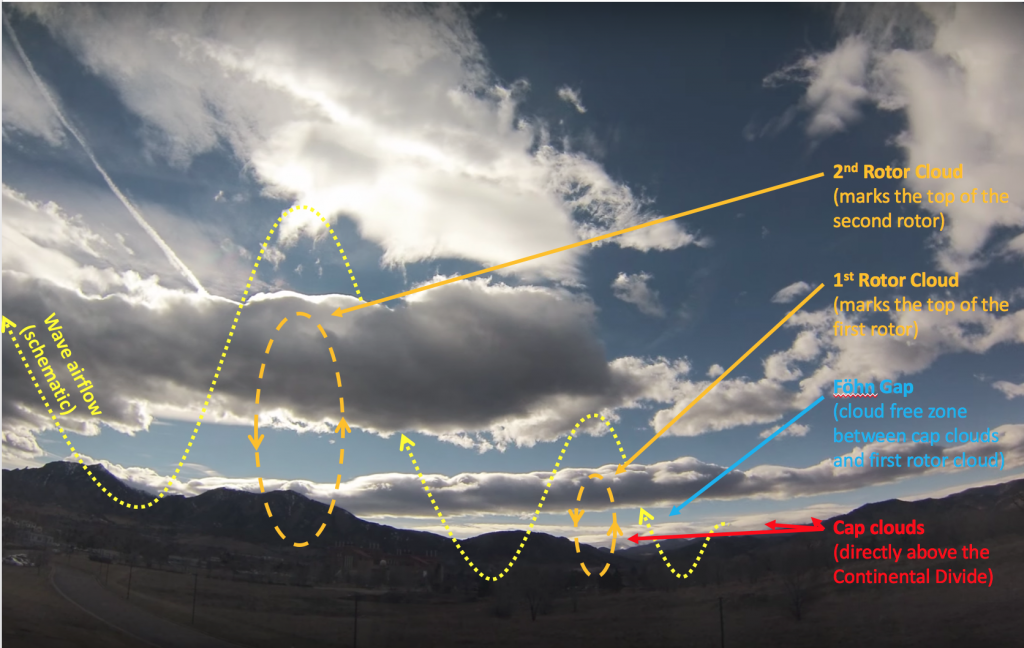

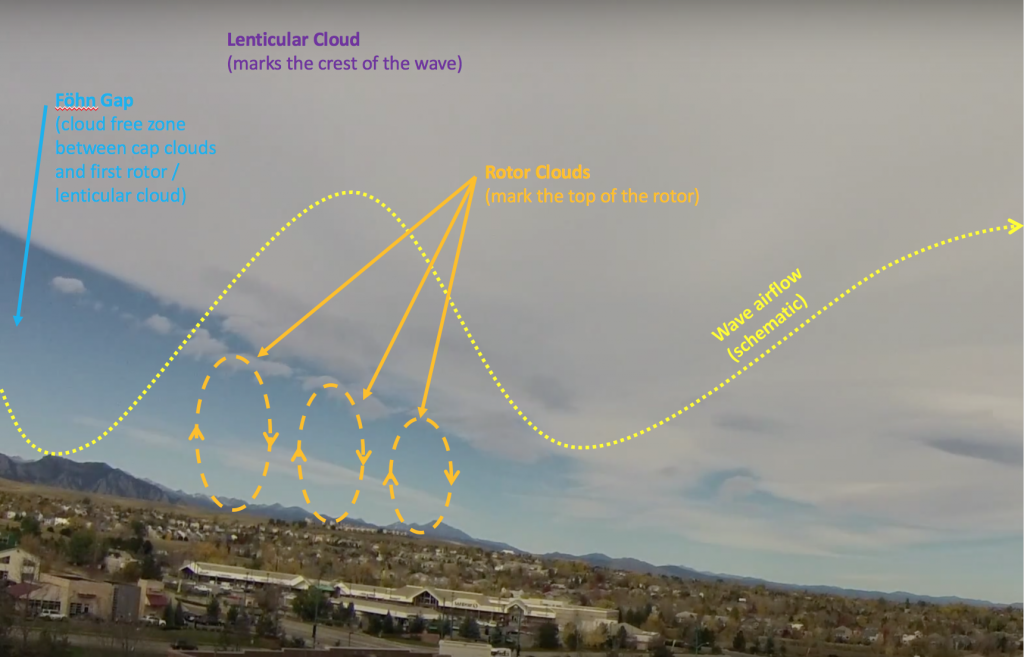

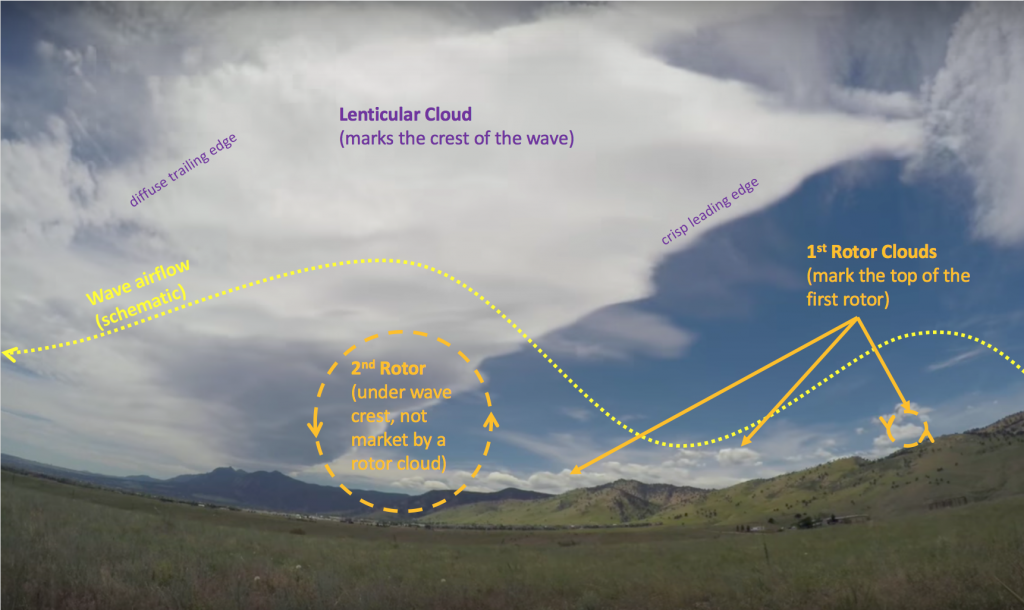

The air in Colorado is usually quite dry throughout the wave season. (Summer monsoon in July and August is really the only time when it can be reasonably humid.) Nevertheless, it is fairly common for rotor clouds and/or lenticular clouds to mark the wave.

The following pictures illustrate some typical cloud formations in wave conditions at Boulder.

The following time-lapse video illustrates the formation of wave clouds over Boulder even better.

- Flying in Wave

Flying in wave is very different from and considerably more challenging than flying in fair weather thermals (at least initially). Locating lift (and sink) is completely different. There is (possibly severe) rotor turbulence to contend with (on tow, during flight, in the landing pattern); climb and sink rates can be extreme (and invisible); flight at high altitudes is associated with different physiological risks than one normally encounters (e.g. hypoxia, hypothermia, hyperventilation) as well as other elevated dangers (flutter risk at high airspeeds: TAS>IAS, flying above and in front of clouds), etc. Flight techniques and tactics differ, orientation can be more challenging, and there are additional rules and regulations to follow (e.g. opening and staying within the wave window, use of oxygen masks, etc.). All those risks can be mitigated by understanding and being prepared for them. In short, it’s worthwhile to put in the time to study in advance to avoid getting caught by surprise and being confronted with an overwhelming situation and not knowing what to do.

I have added a lot of useful information in a special section about wave soaring that’s a good place to start.