Boulder is an outstanding place to soar. But it is also quite technical and the technicalities start at launch. At many soaring sites a pattern tow to 1000-2000 ft AGL is normally sufficient to climb away. Sometimes Boulder can be this way, too. But only sometimes. More often than not, launching from Boulder can be a real challenge. Once you’re up under the clouds, the soaring is breathtaking. Until you’re up, it can be breathtaking too, but for different reasons.

This article is all about launching from Boulder so you can really enjoy the soaring and go places: Where should I tow to? Where will I find lift? How high should I release? This article is meant to help anyone who is new to soaring in Boulder and has these fundamental questions. I know I did when I started out.

In April of 2021 I gave a presentation specifically about this subject. Here’s a recording of it from the SSB YouTube Channel:

You can also download a .pdf file with all the presentation materials. It’s a bigger file so it may take a little time to download.

What Do Other Pilots Do?

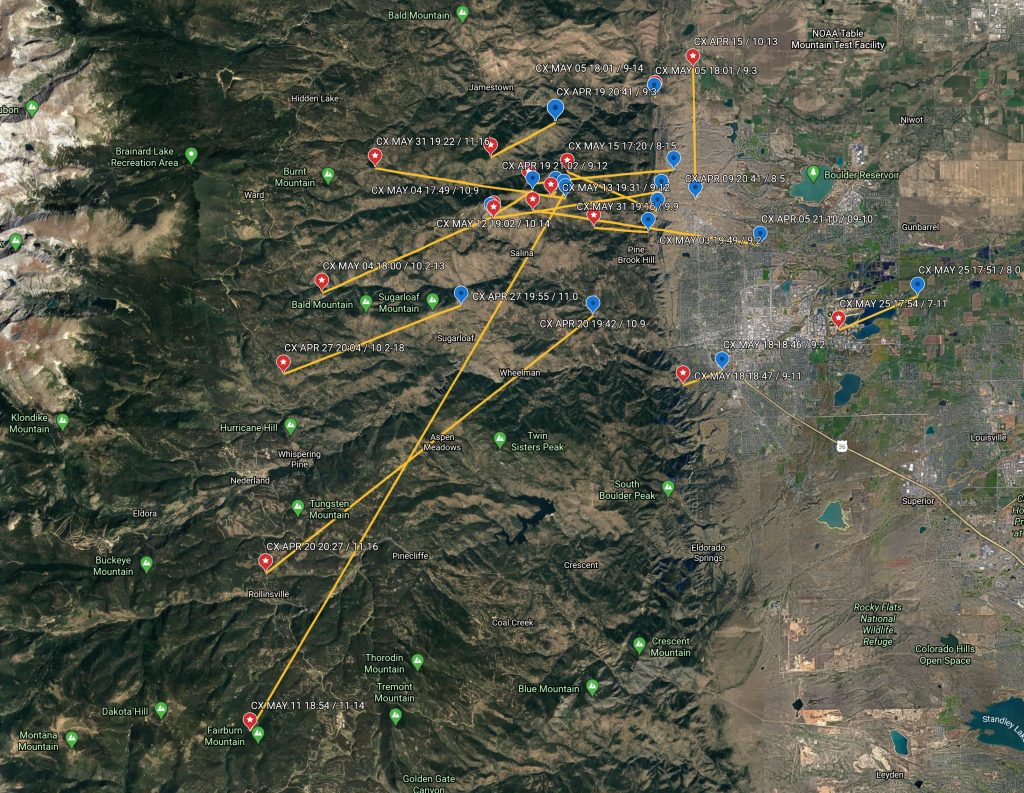

To address these questions I examined 51 cross-country flights from Boulder that were uploaded to OLC in April, May, and June of 2019. (I generally looked at flights with a minimum distance of 250 km to ensure that I captured days with reasonable soaring weather. Also, I wanted to focus on thermal conditions and therefore excluded flights that were obviously flown in wave. Only flights that started via aerotow are included, i.e., the chart does not include flights with self-launching gliders).

The blue dots mark the release points and the red dots mark the location of the first “good climb”. Yellow lines connect the blue dots with the corresponding red dots.

Blue dots are labelled with the pilot’s initials (or the glider’s contest ID), the date and time of release (time is indicated as UTC), and the release altitude in thousands of feet MSL. Similarly, red dots are labelled with the same initials, the date and time when the climb started, and the altitude of the climb (from-to).

If you want to zoom in and look at the chart in detail in Google Earth, you can do so here. All flights are downloaded from OLC. I.e., you can look up any particular flight and examine the flight paths taken.

Typical tow routes:

- Only ~15% of XC flights started with a release near the airport. Only one of them was in April, the other ones were in May and June. (Climbing away from the pattern seems to be easier later in the day and especially in the summer months, after the morning inversion over the prairie has completely burned off. The first good thermals of the day are almost always over the hills.)

- The most popular tow route is to the northwest (more than 50% of all tows), towards the entrance of Lefthand Canyon, and from there along Nugget Ridge. This makes sense because Nugget Ridge faces south-east and therefore gets a lot of sun exposure in the morning.

- More than 25% of all releases occurred directly along Nugget Ridge. If in doubt, this is probably the best place to tow to. The release altitude along Nugget Ridge is typically between 9,000 and 10,000 ft MSL, sometimes higher.

- In 17% of the launches, pilots released on the way to Nugget Ridge before reaching the foothills, most often at an altitude of 8,000 to 9,000 ft MSL. In most cases they will only do so if they are confident that they can climb from the point of release.

- 20% of tows were to the south towards Eldorado Canyon. In half of those cases, pilots were able to release on the east side of the Flatirons, typically between 9,000 and 10,000 feet. If no lift is encountered (the other half of the cases), the further direction of tow west of the Flatirons varies greatly depending on the day’s conditions.

- On days with a strong convergence line there is often only weak and low lift to the east of the convergence. Such days require tows further to the west and higher release altitudes (typically 11,000 – 12,000 feet).

Location of the first good lift:

- With few exceptions, pilots did not release until they encountered some lift. However, only in the small minority of cases (10-20%) were they able to achieve a good first climb right at the release point.

- In about 30-40% of the cases they succeeded in locating their first good climb nearby (within 2-3 miles of the point of release).

- However, in about half the cases, pilots had to explore a significant area before they found their first good climb. The exploration was rarely a straight line (in this respect the chart can be misleading). Most often, pilots were working their way around in weak lift and sink before they were able to locate the first good climb. Looking at a pilot’s release time (blue dot) and the time of the associated first climb (the connected red dot) provides a hint as to the length of that exploration. Sometimes an hour passed between release and the first good climb. (All the flights are on OLC so anyone can look up individual traces that they find interesting.)

- In the majority of cases one can see pilots pushing further west into the higher hills as they were looking for lift (most of the red dots are further west than the associated blue dots). The ability to push further west (where the lift often tends to be better) is obviously limited by the need to stay within safe gliding distance to Boulder.

- Sometimes – especially in strong convergence conditions – the first good climb is as far to the west as the Peak-to-Peak Highway, sometimes even further beyond. E.g. during my flight on April 20 2019 I released in still air at 12,000 ft MSL over Boulder Canyon and did not find a first good climb until 40 minutes later when I was close to Niwot Ridge at 12,500 ft MSL.

What Can We Learn from a Self-Launching Motorglider?

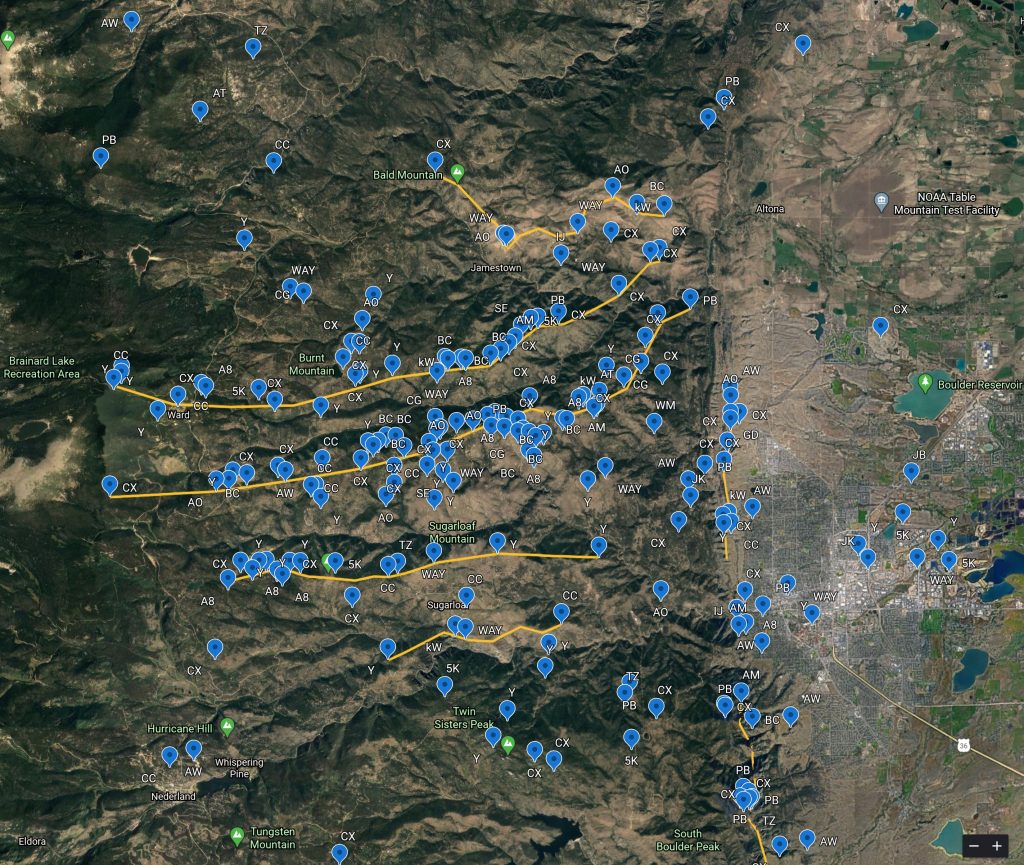

The following chart provides a similar set of data from the same time period. This time, we are looking at flights of CX, Boulder’s most prolific cross-country pilot. CX is a self-launcher and instead of the release points, the blue dots indicate the location where the pilot turned off the engine. In some ways this is even more insightful than the data from aerotowing because the pilot of a self launcher has obviously the most immediate control over the direction of the flight path between takeoff and “release”.

To view the file in more detail in Google Earth, click here.

Some of the same points observed earlier are now amplified even more:

- In the majority of cases the pilot chose an initial route under power that led to the northwest.

- The “engine off” altitudes were very similar to the release altitudes of aerotowed gliders.

- The engine turn-off points were most frequently right above the first hog back or above Lee Hill.

- Several of the first good climbs were right above Lee Hill or above Bighorn Mountain. This suggests that Lee Hill and Bighorn Mountain might be equally good thermal sources as Niwot Ridge – Niwot Ridge is just along the typical tow path.

- In almost all instances, the pilot immediately pushed further west after turning off the engine. In several cases these westward pushes went beyond the Peak to Peak Highway before the pilot encountered the first good climb of the day. (Interestingly, the pilot spent less time between the “power off point” and the location of the first good climb than the pilots that started via aerotow, even when the first good climb was further away from the “power off point”. This is likely a reflection of the pilot’s vast experience but also shows that pushing west tends to pay off, provided that a safe altitude can be maintained at all times.)

After all this analysis, let’s come back to the three questions:

1) Where will I find lift?

It obviously depends on the weather. Each day is different. However, unless there are strong clues in the sky that suggest otherwise, the following is worth considering:

- The first lift of the day is almost always above the hills. Climbing away from the pattern near the airport is possible but it can take a long time and the odds of having to relight are considerable – especially if it is early in the day. If you want to skimp on tow fees it’s best if you like betting games.

- Close-in, the most reliable locations in the morning are south-east facing slopes such as Niwot Ridge, Lee Hill, and Bighorn Mountain.

- Further west, the lift tends to get better (although this is not always the case.)

- On some days, especially days with a strong convergence (i.e. when an easterly flow from the plains meets with a significant westerly flow coming over the divide), the area east of the convergence can be very challenging – i.e., the climbs tend to be weak, top out close to the ground (sometimes at just 500 ft AGL, sometimes at 2000 ft AGL), and are capped by the inversion and/or a wind shear layer. On such days the only way to get away is to find lift on the west side of the convergence. (If you look at flight traces you can often see this phenomenon by a glider’s wind drift in a thermal: east of the convergence line the drift is from east to west; west of the convergence line the drift is from west to east.) The location of the convergence line varies – sometimes it is close to Boulder, sometimes it is further west than the Peak-to-Peak Highway. Skysight has a convergence forecast – it’s very useful but not always accurate. Other weather sites can give you the information as well if you know how to find it (look for vertical velocity).

2) Where should I tow to?

- In the morning, look at the soaring weather forecast for the area between the airport and the Continental Divide. Thermal height and depth, thermal strength, convergence, and buoyancy/shear ratio are the most important data points to consider, along with wind direction and strength. Look at these indicators for different times of the day, hour by hour for the times you consider for launching.

- When you get to the airport, look at the sky. Is it consistent with the forecast or do you see something different? Forecasts are great but they are always trumped by reality.

- If you have a strong sense where the lift is going to be, that’s where you want to tow to.

- Often, the situation is a bit ambiguous. If you’re not sure if going south or north is best, go with a standard northwest tow.

3) How high should I tow?

- If you encounter lift on tow right after takeoff be at first a bit skeptical. It might top out at 7000 ft and you won’t get to the hills (safely). As you’re heading northwest and are climbing above 8000 ft it is normally a good bet to take the next good lift that you encounter. Just be prepared that it may not last and that you have to move around before you find the first good one for the day.

- Often there is no lift at all (above 8000 feet) before you reach the hills. There’s nothing you can do but wait a) until you find it; or b) until you are high enough that you can release and push further west until you find it on your own.

- Releasing in the first lift when you reach the hills can be a bit of a gamble. Don’t pull the release as soon as the vario shoots up. Wait a few seconds to see if it lasts and if it is big enough to turn in it. (If you’re still below 9000 ft and can’t make the first climb stick and gain at least another few hundred feet, you might find yourself heading back to the airport.)

- On some days you tow into the hills and you reach 10,000 ft and there is still nothing. Now you are faced with another gamble: do you hang on and wait until you encounter lift or do you release and look for it on your own? Once again: it depends. This time, it depends on your assessment of how far west you have to go before you find it. If there are clouds they may provide a good clue. However, if there’s a westerly wind, assume that you have to fly all the way to their western edge and perhaps a little beyond for that is where the lift often is. You will lose altitude pushing west, you may need some altitude to explore, and you need to maintain enough altitude to come back out if you find nothing. You may also encounter sink. It’s not easy to get this right. If it’s a strong convergence day and the line is at the Peak to Peak Highway or even beyond, then a release at 12,000 ft is often the minimum you need. It also depends on the performance of the glider you’re flying. This is an interesting mind game because you’ve already spent a lot of money on the tow and if you release a tad too early you may be back on the ground in 30 minutes.

How Do I Work My Way Up?

We all want to climb quickly so we can “connect” with the clouds. Once we’re up there things are easy. But getting there can be a major challenge. (And on some days it is simply impossible.) But you can work to improve your odds. This section is about improving your odds, especially on difficult days.

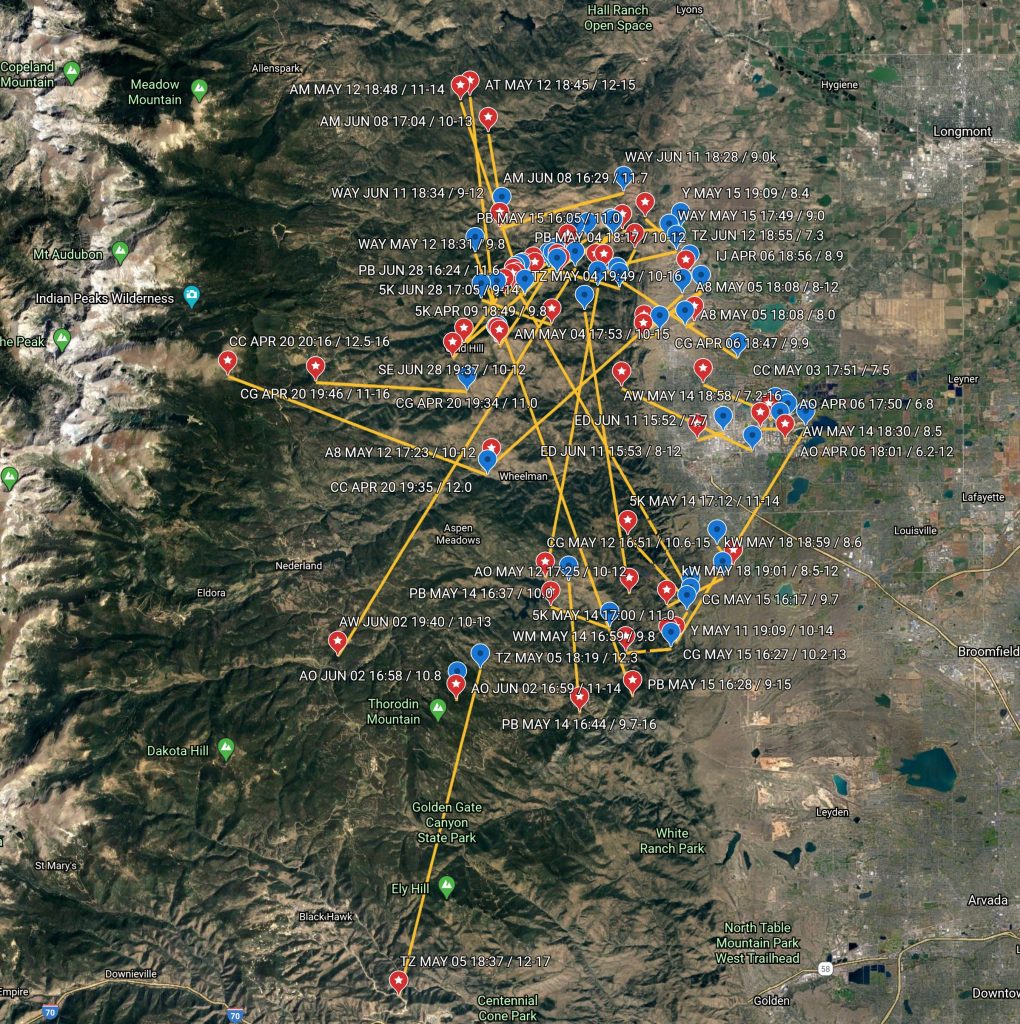

The following chart shows the locations where pilots have found lift from low altitudes. Each dot represents the starting point of a climb that started an an altitude at or below 1500 feet AGL. (Obviously the altitude MSL varies based on the terrain.) The pilot’s contest ID or initials are shown as well. The source data are all flights originating from Boulder that were uploaded to OLC in 2018 and 2019.

You can readily see that the lift is indeed where you would expect it: the vast majority of all climbs originated from one of the main (south or south-east facing) ridge lines marked in yellow. You can click here to see the chart in Google Earth. This will allow you to zoom in and look at the details.

Now, it’s important to note that not all of these climbs were “good climbs”. In fact, the vast majority were quite weak and soon topped out. When pilots are forced to seek climbs from such low altitudes it usually is an indication of a convergence day – i.e. they must get further west before they will find stronger lift that will reach higher.

So what’s my strategy when faced with a difficult day?

As I explained before, the lift tends to get better as I push further west. This is particularly true on convergence days where the only good climbs are west of the convergence line. How can I get there? If there’s no lift over the lower foothills at all, I may have to take a really high tow. (Here’s one such case where this was indeed the only option.) However, most often there is at least some lift over the hills, and in this case a practical way is to take a series of small, mediocre climbs, “milk them” as high as they will go to build up altitude in excess of the safety margin, then “invest” that altitude by progressively pushing further west until I find “a good one” that allows me to connect with the clouds.

- Let’s say I release along Nugget Ridge (the second yellow line from the top in the chart above) and my release altitude is 9,000 ft.

- I know I need a climb soon, otherwise I will be heading back to the airport. I explore along the ridge. If I find a climb, even if it’s weak, I take it. Every bit of altitude counts. The higher I can climb, the more excess altitude I gain over my safety margin. This then allows me to invest that altitude to head further west without taking any risks.

- Le’t say I manage to climb to 10,000 ft. This allows me to continue two or three miles further west but my situation is still tenuous and I need another climb soon. Often I can find it just 1 or 2 miles further along the ridge. It might take me to 10,500 ft.

- That makes me feel better because it might just be enough to take me to Gold Lake where I have often found another climb. (I believe the contrast between the cold lake and the warm surroundings is a good thermal trigger.) My personal minimum for being at Gold Lake on a benign summer day with little wind is 10,000 ft in a Discus. That’s 1,500 AGL.

- If I can climb just a little higher, another good spot to explore further is above the town of Ward. Ward lies in a wind protected bowl and receives a lot of sunshine in the morning. (I’ve often noticed when driving through Ward around noon, that the ground temperature is considerably higher than the temperature in the canyon below and also much higher than the temps along the Peak to Peak Highway.) Ward lies at 9,200 ft and in the Discus I want to be above 10,500 to explore in this area.

- If I can get another climb at Ward, I have found that the winter trailhead parking lot for Brainard Lake can be a great thermal source. The ground elevation is 10,000 ft and my personal minimum to arrive there is 11,000 ft (again, on a benign summer day and in a high performance glider).

- If I made it this far, the chances are pretty good that one of these climbs is a “good one”, allowing me to get much higher and connect with the clouds.

- However, if I am unable to find lift at any stage along the way and I drop below my personal minimum altitude, I am immediately heading back east, and, once I find lift, I try again.

- If I have to head back east and one of the climbs along my route was quite reasonable, I might be heading back to the same spot. If not, I will fly across Left Hand Canyon and try along the next ridge further south.

- The area near Gold Hill is often a good thermal source, and especially the south-face of Bighorn Mountain. Take another look at the chart and see how many low altitude climbs originated from this area. Bighorn Mountain is quite prominent and my personal minimum in this area is to be at least at the same altitude as its peak.

- At any stage, when I find a climb that gives me an extra safety margin, I tend to reverse course, push back west again and try once more. In this case, I will often try the same game along one of the other ridge line if the one I tried earlier did not work.

Finally, here are some important tips to stay safe:

- Always stay within safe glide to Boulder. Don’t trust the flight computer when you are low over the hills, for most computers will not take terrain obstacles into account (including the S100). It also does not assume that you may have to fly through sink (which is always a possibility). When you have any doubt at all, head back out immediately. Your personal safety minimums must be appropriate for your skill level, for the performance of your glider, your familiarity with it, and for the weather conditions.

- Never let yourself get trapped low behind terrain obstacles such as the Flatirons or Thorodin Mountain.

- Always stay well above the canyon ridge lines. Most often the lift comes off the tops (look at the chart!) and once you fall below, you might find nothing but sink and life can get very scary.

- If you hit sink on your way west (perhaps even on tow!), remember you will also hit sink flying back east. Add that to your safety margin.

- Do not circle low above terrain (e.g. a mountain or a ridge line). Whenever you’re flying in proximity to terrain, you must add extra airspeed. (This can be a nuisance because you lose climb performance but being unable to climb is a lot better than spinning in or crashing into the mountain.)

- If you have enough altitude to safely push west and explore, seize the opportunity: now is the time to do it. Every 100 ft of altitude counts. If you waver and lose the necessary safety margin you may not be able to earn it back. Here’s one such experience.

I hope this has been helpful. Have fun, and above all, fly safe!