Yesterday was my sixth attempt to complete a Diamond Distance task. The basic requirement is a pre-declared 500km task with up to three turn-points. My strategy for setting these types of tasks has improved over time. I now adhere to the following principles:

- Select a task area that provides the best soaring weather over the course of the day. Some parts of the task area might work best in the morning and other parts might work best in the afternoon. Thermal height and depth, thermal strength, convergence lines, development of cumulus clouds, over-development risk, wind direction and speed at different altitudes, buoyancy/shear – all of these things matter, and I try to account for all of these factors. I predominantly rely on Skysight for providing the forecast because it makes it easy to examine all factors for the entire task area throughout the day.

- Place the first and second turn point furthest away from Boulder and place the third turn-point closer to home such that the last part of the flight can be flown within glide range of Boulder. This drastically reduces the likelihood of having to land out when the day might die towards the end.

- Pick accessible turn-points. I.e., avoid turn points that might be difficult to reach, such as high mountain peaks. Each turn point should also be in an area of forecast lift at the approximate time or rounding it.

- Ensure accessible landing places along each task leg. The spacing of these is most critical early and late in the day. The part of the task that lies during the best part of the soaring day (approx. between 1pm to 4pm) can be the most challenging.

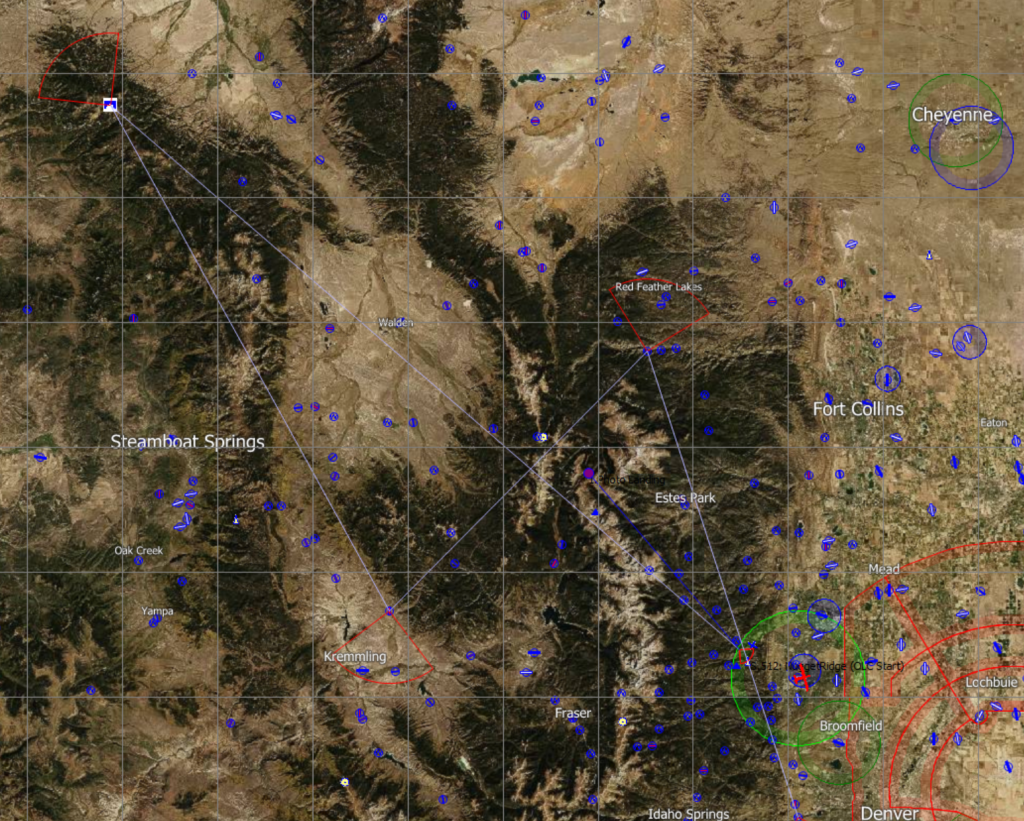

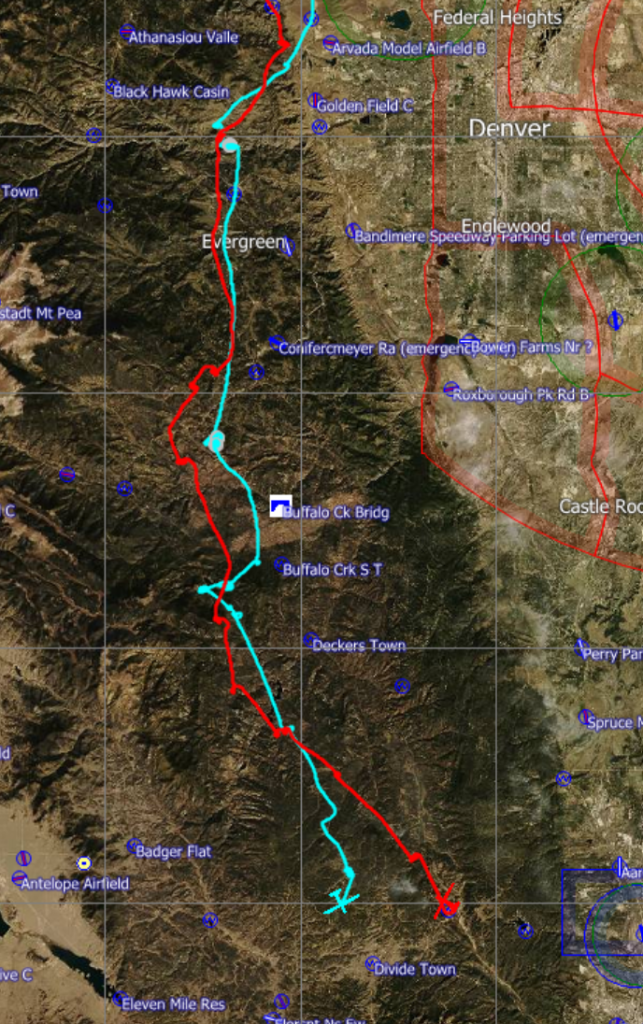

Yesterday’s task adhered to these principles.

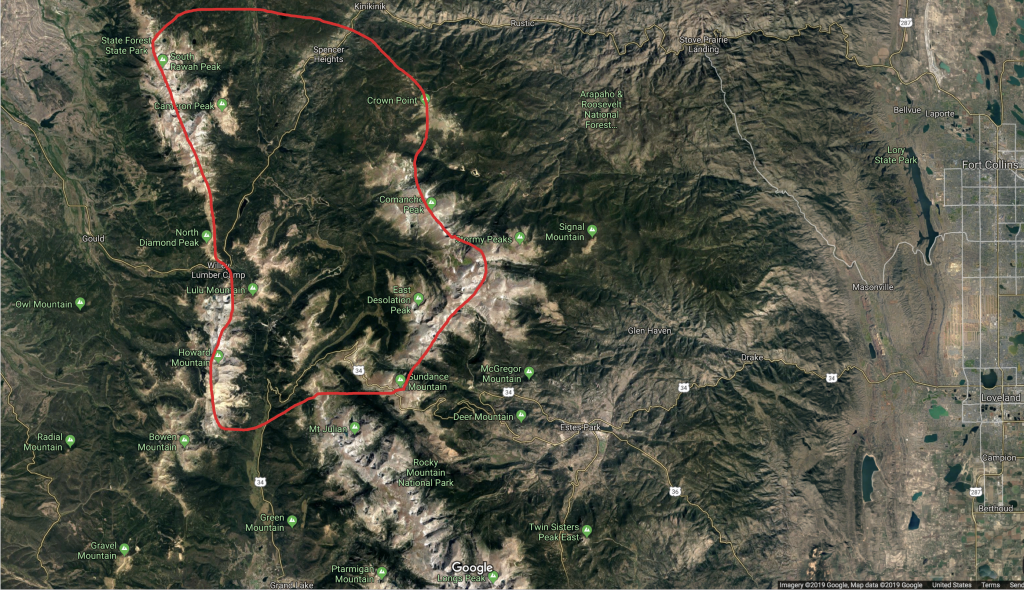

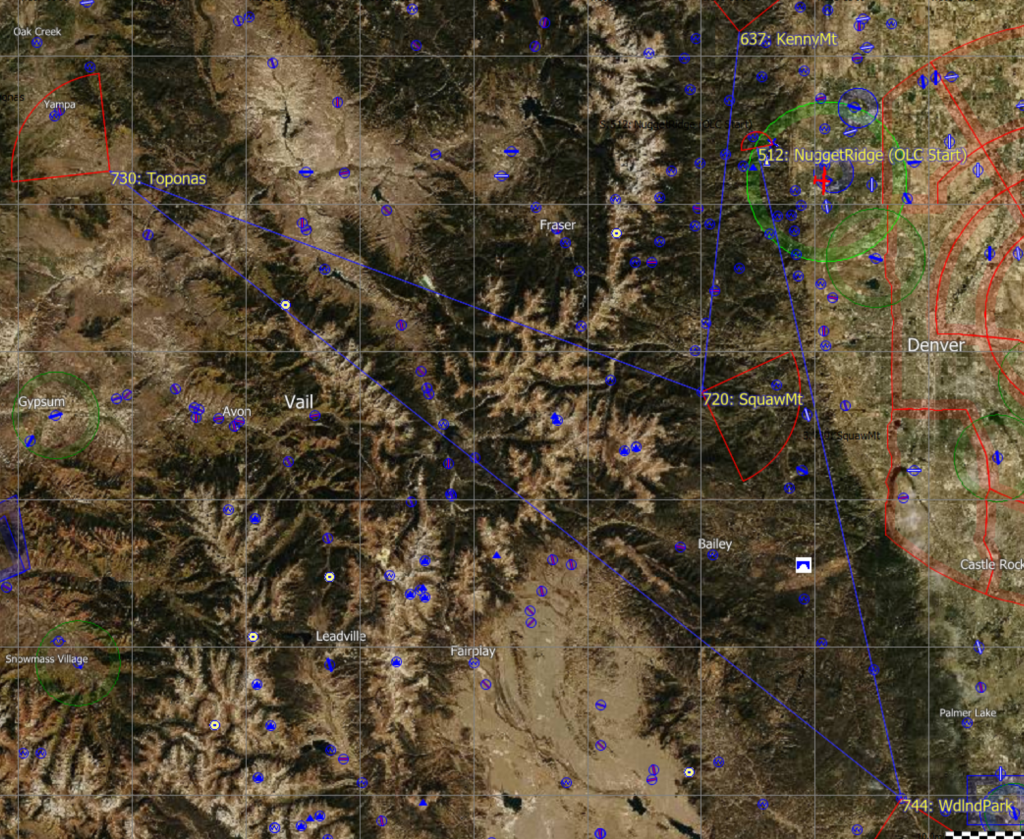

- The Start point was at Nugget Ridge as I planned to take a northwest tow and Nugget Ridge is right on the typical tow route in the morning. Putting the start to the north while my first TP was in the south would also ensure that I would be in close proximity to the airport as I would try to get underway. Thanks to Pedja Bogdanovich for this tip!

- I set my first TP at Woodland Park, a few miles north of Pikes Peak. Skysight forecast a convergence line to the south in the morning along the foothills, and the first cumuli were projected along that line. Cloud bases – which were generally a bit lower than I liked – were forecast to be higher to the south than to the north. Also, the south was projected to be less windy. (Strong winds can shear off the thermals, making it harder to climb.) Perry Park was my go-to landing spot on the southbound leg.

- My second TP was at Toponas, due west of Boulder. This would make for a challenging second leg across some difficult terrain but the route was supported by the forecast and my fall back plan was to go back north along the convergence before heading west. Potential landing spots were Perry Park, Henderson Ranch (in the nw corner of South Park – thanks to Tom Z), some fields north of Silverthorne, the airport in Kremmling, as well as some fields near Toponas. While the second leg was the longest, it would not increase my distance from Boulder.

- My third TP was Squaw Mountain, located south of Idaho Springs on the ridge that extends from Mt. Evans towards the northeast. I have often found lift in this area even in west wind conditions (however, you do not want to get any closer to Mt. Evans on the lee side on west wind days). Kremmling and Granby would be easy-to-reach landing spots west of the divide on this leg should a land out become inevitable. Squaw Mountain is already relatively close to Boulder and 13k feet would put me in glide range.

- I set my Finish at Kenny Mountain, east of the Twin Sisters. This ensured that my entire last leg could be flown within glide range of Boulder. (I would have to round Kenny at 11k+ feet to have Boulder in final glide. Having the finish point away from the airport (but within final glide) has the side benefit that rounding it would invariably ensure compliance with SSA rules for Diamond Distance tasks. These rules require that the finish altitude is not more than 1000m below start altitude.)

Total task distance was 312.1 miles or 502.2 km (plus the final return to Boulder).

First Leg

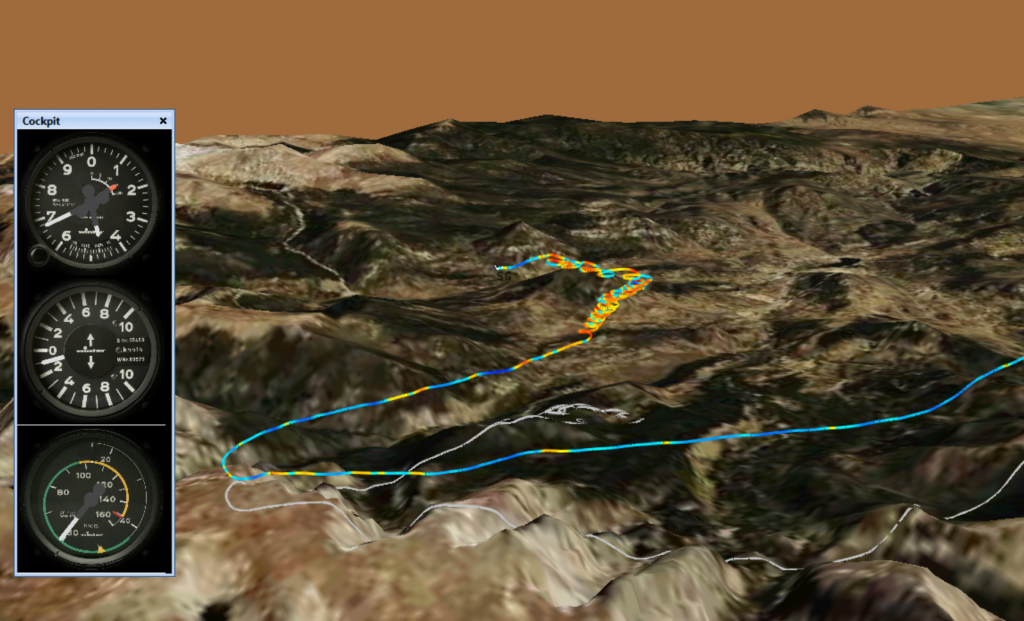

Fortunately the day started early and there was no need for a big mountain tow. I took off at 11:12 am, released at 11:21 and flew across the Start line at 11:30, at an altitude of 11,000 feet.

Having my first leg pass the airport meant I could get going on course without first having to climb up high.

There was good lift along much of the first leg even though I chose to fly in thermals several miles west of the convergence line because the cloud bases were significantly higher than along the convergence. Following the convergence might have been a bit faster but keeping a good altitude was more important to me along this stretch because there are very few landing options and the only good one is the private airfield of Perry Park.

It was nice having (unplanned) company on this first leg. 5K was heading to Pikes Peak and both of us left Boulder at about the same time. Flying side by side at times helped to see as to who had the better line.

I averaged 81kph on this 128 km leg and rounded Woodland Park at 12:56pm.

Second Leg

Looking ahead after turning Woodland Park the second leg seemed daunting. The distance to Toponas was almost 200 km, much of it across challenging terrain and tall mountains. The cloud bases were still relatively low, around 16,000 feet. This may seem quite high for those used to flying at lower altitudes, but it really isn’t when considering that much of my direct route ahead led over unlandable terrain between 10,000 and 13,000 feet.

The area north of Woodland Park is a bit lower but that makes it all the more insidious. There are no places to land and there is an elevated ridge to the east (and to the west). It is imperative to maintain an altitude that allows clearing the eastern ridge to glide out to Perry Park. The further west one flies, the higher one has to be. I scared myself once before in this area and was determined not to let it happen again.

I quickly found some good climbs back to cloud base and got myself back on course, passing Mount Evans on the west side.

Unfortunately, the cloud bases had still not risen much beyond 16k feet. I made it to the ridge south of Keystone Mountain and then stopped, milling around in middling lift unsure what to do. There were some clouds ahead but they did not look reliable. I could definitely glide ahead towards Silverthorne but I was concerned that I might get stuck in the valley.

I also wondered about the impact that Dillon Reservoir would have on the thermals. Ironically, the best looking cloud seemed to be right above the lake. I was not willing to trust it. There was a 12-16kt southwesterly wind at my altitude so I figured I might be able to ridge soar along the south-west facing slopes of the Ptarmigan Range north of Silverthorne if I could get there close to the top of the ridge line. Which seemed possible, although by no means certain. I also considered the potential impact of Eagle’s Nest Ridge, upwind of the Ptarmigan Range. This ridge was even higher and I figured it might mess with the wind direction. It could also mean lee side turbulence and sink. The more I thought about it, the more uncomfortable I became.

So after a lot of hesitation, evaluation, and considering my options, caution prevailed and I decided to return to the east of the Front Range. I remembered what I learned in Austria: when flying in big mountains, especially ones that one is not intimately familiar with, it is always best to stay well above the ridges. I was not certain that I could do that. Maybe cloud bases of 16k were simply not enough for my first trip to the west…

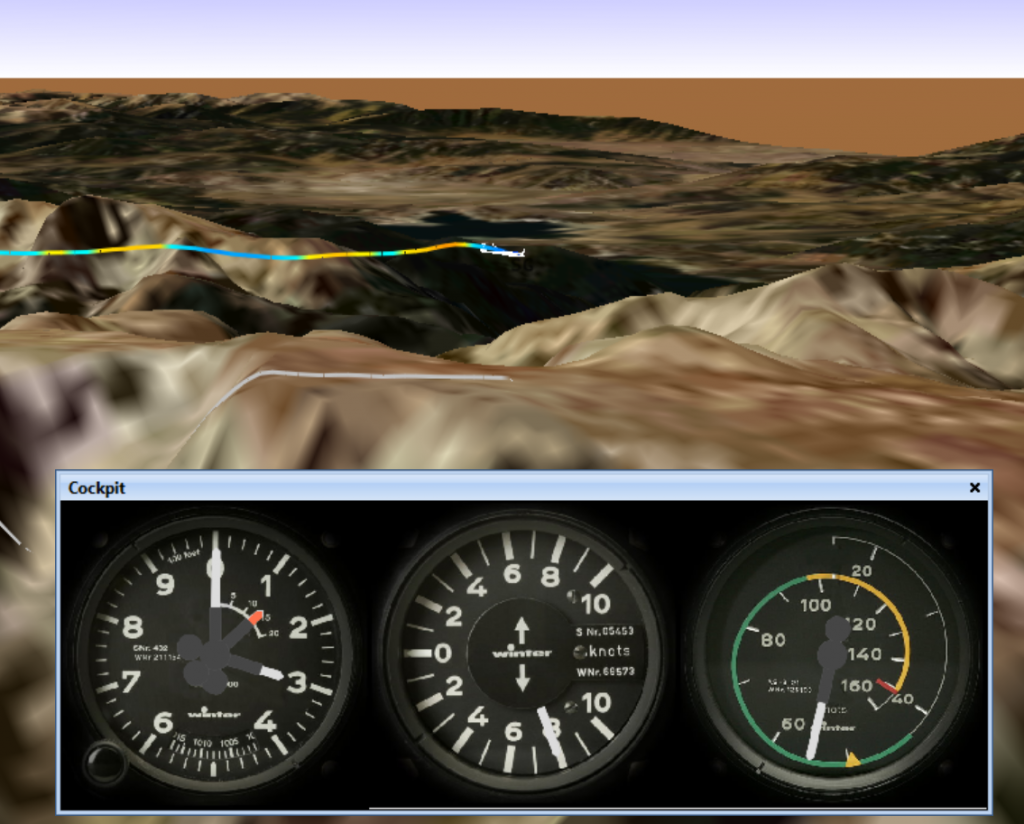

I crossed over Mt Bierstadt and Mount Evans, heading north towards the Divide. Just before I got to Winter Park, I spotted my opportunity: a line of clouds had developed in westerly direction. I had just climbed to almost 17,000 ft, i.e., cloud bases were finally rising. The airport of Granby was within glide range. No mountain ridges were in the way. I had wasted some time but it was still early enough in the day. There were no more excuses. And with that I resolved to jump to the west.

Crossing the Divide was a big moment. It felt daunting and liberating at the same time with the former gradually giving way to the latter. I reached full acceptance once the distance to the divide had increased to the point where gliding right back was no longer possible without gaining altitude first. At that point I just focused on one thing: progressing forward and not run out of time.

Whenever you fly over new terrain your inclination – rightfully so – is to stay high. But staying high also comes at the cost of being somewhat slow. Centering thermals takes time. Centering and climbing in weak thermals takes even more time. Centering and climbing in weak thermals while going into a headwind is even worse. I was wondering: how high is the working band? How low can I afford to get without having to spend even more time digging myself out. These were questions that had no answers for me. So whenever I found reasonable-seeming lift I turned at least to test it.

Fortunately the terrain between the Divide and Kremmling looks a lot more hospitable than the terrain over the foothills. If the clouds are high enough you can easily keep an airport (first Granby, then Kremmling) in glide. And even in the worst case of hitting massive sink – which actually seems a lot less likely given that the terrain is more mellow – there are often some farmers’ fields around where putting the glider down safely seems possible.

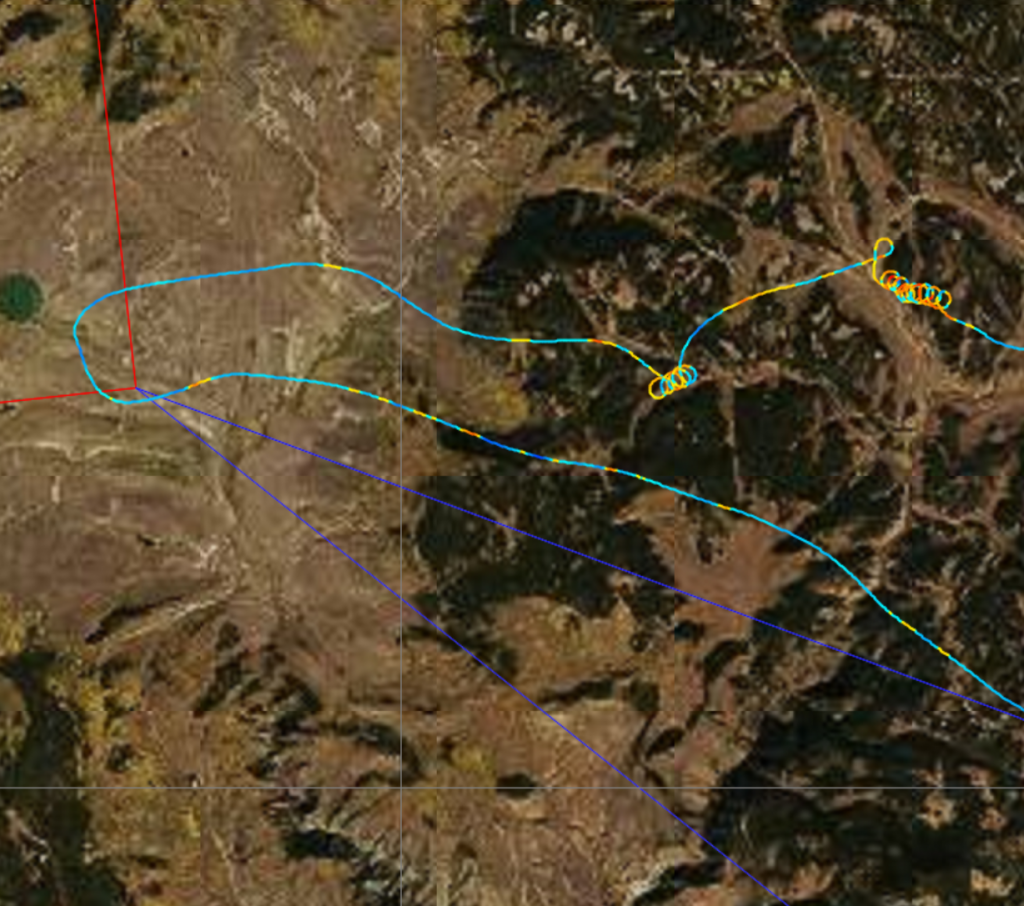

I managed to stay high enough to never get out of glide range of an airport. This saved me a lot of stress albeit at the cost of speed. One hour after crossing the Divide I finally got my turn point in view, still 15 miles away. I had expected a little town but all I could make out from the distance was a road intersection.

The immediate issue at hand was that I had almost reached the end of the clouds before a significant blue hole above the lower terrain to the west. I tried each of the last remaining three little clouds and finally found a good climb to cloud base under the last one allowing me to head out into the blue, round the turn point and stay within easy glide of Kremmling the whole time.

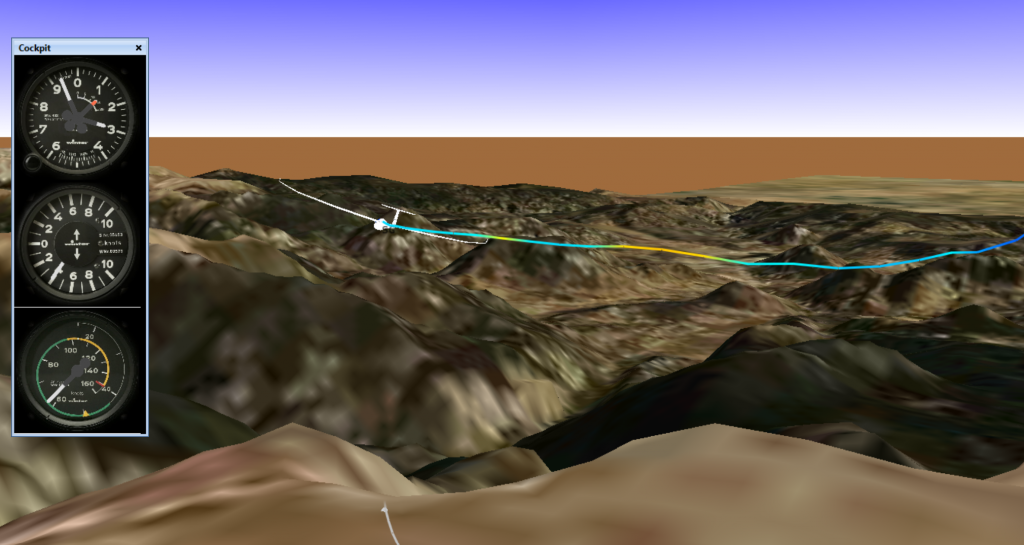

I rounded Toponas at 4:16 PM. The Divide looked very far away. But the sky ahead looked great, considerably better than on the outbound leg. I was hoping it would stay this way for a while for I had a lot of ground to cover. Looking at the clouds I was pondering which of the two most promising lines to take.

The southerly line (the one to the right of the nose in the picture above) was better aligned with my 3rd turn point but it would keep me on the west side of the Divide for longer. The northerly line (the one to the left of the nose) went directly towards Granby and the nearest point on the Divide. My number one goal at this point was to make it back over the Divide, my number two goal was to complete my task. I chose the northerly line.

A dark flat-bottomed cloud slightly north of Kremmling promised compelling lift. I figured it would be worthy of a small detour.

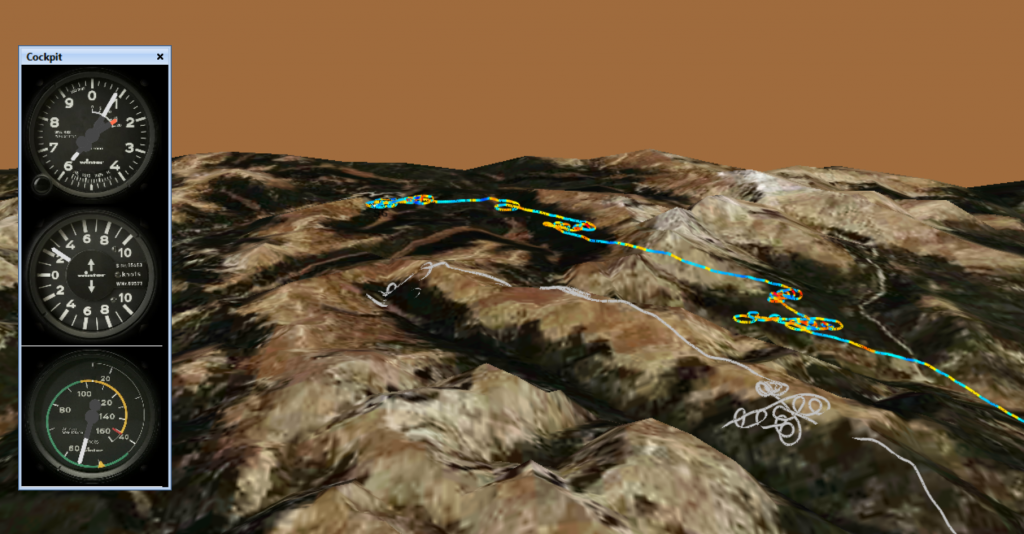

Thanks to lift like this and the wind in my back, progress on the return was blazingly fast. Even despite little mistakes like the one in the picture below.

Only 40 minutes after rounding Toponas I was already approaching the Continental Divide.

These clouds were the best of the day. I barely had to stop for a circle or two. Most of the time I could just dolphin up in lift and then drop the nose to bridge the short gap to the next cloud.

Approaching the Divide was a non-event and although it was already 5:15 pm, the day was still looking great. Now my mind could start to focus on something else: was it still possible to complete the task? I had another 110 kilometers to go.

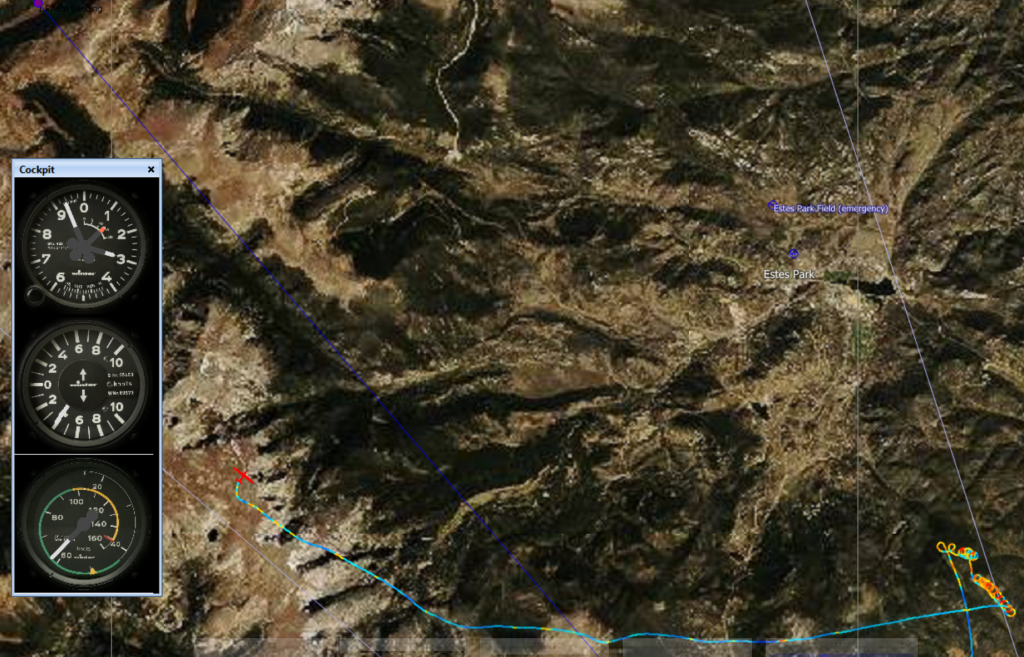

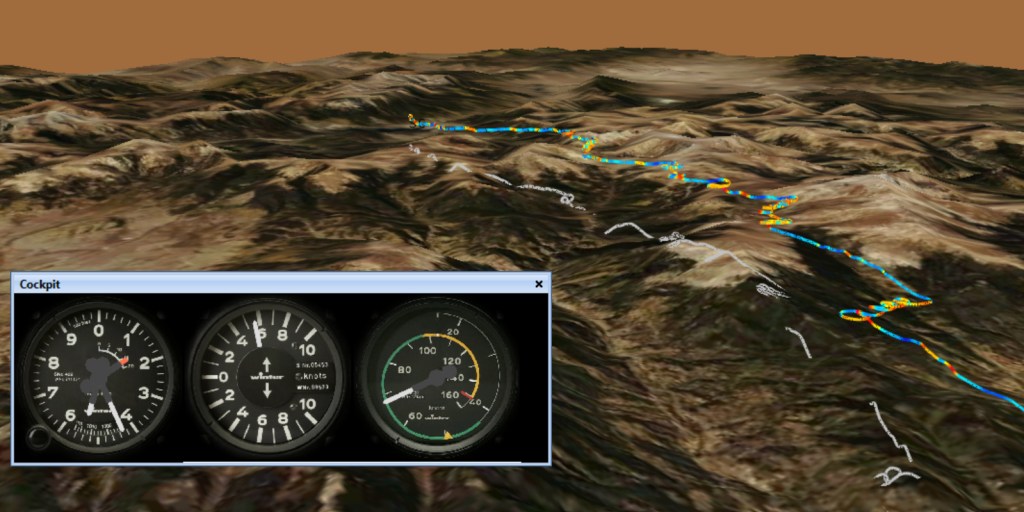

A big blue hole greeted me as I crossed the Divide via Mt. Neva. The air on the east was very turbulent and I hit massive lee-side sink. I pushed the nose down, accelerated to 90+ kts and headed straight to the nearest spot along a long cloud street that seemed to stretch from Longmont towards Berthoud Pass but then turned away from the Divide towards Idaho Springs and continued in south easterly direction beyond.

As I approached the line I could readily see that it was generated by a convergence of different air masses. I connected with the line southwest of Rollinsville and immediately found myself in strong lift. After a few turns in turbulent rising air I continued southbound along the line.

This line seemed like a present from the powers to be: it was perfectly aligned to curve around towards my third turn point at Squaw Mountain.

I turned Squaw Mountain at 5:33 pm with another 70 kilometers to go to the Finish at Kenny Mountain.

Instead of heading straight to my goal in the north, I backtracked along the line I had just come from. This required an almost 40 degree deviation from the direct course line (see flight trace above) but it was most certainly the fastest route.

Without a single turn I continued to climb along the line, which allowed me to make rapid progress.

I continued in straight flight along the line until I reached 16,000 feet near Gross Reservoir. I had 35 kilometers to go to my Finish Point at Kenny Mountain and from there another 20 kilometers to get back to Boulder. Barring some extreme sink event, I had more than enough altitude to complete the rest of my flight in a single glide and arrive back in Boulder with height to spare.

I told myself that it was still too early to get excited. My route would take me into the lee of the Twin Sisters. I still could not be certain.

The big sink did not come. At 3 minutes past 6pm I rounded my Finish Point with an altitude of 12,000 feet – 1,000 feet above my start altitude, and 1,500 feet higher than I needed to safely make it back to Boulder. It was a great moment.

After five failed attempts, I finally had made my 500 km Diamond Distance. And it was in good style with my first excursion to the west of the Continental Divide.

I hit a good line on the return to Boulder and had enough altitude to spare for a celebratory fly-by of the Flatirons before returning to the airport where I landed at 6:24 pm after 7 hours and 12 minutes in the air (my longest flight duration thus far).

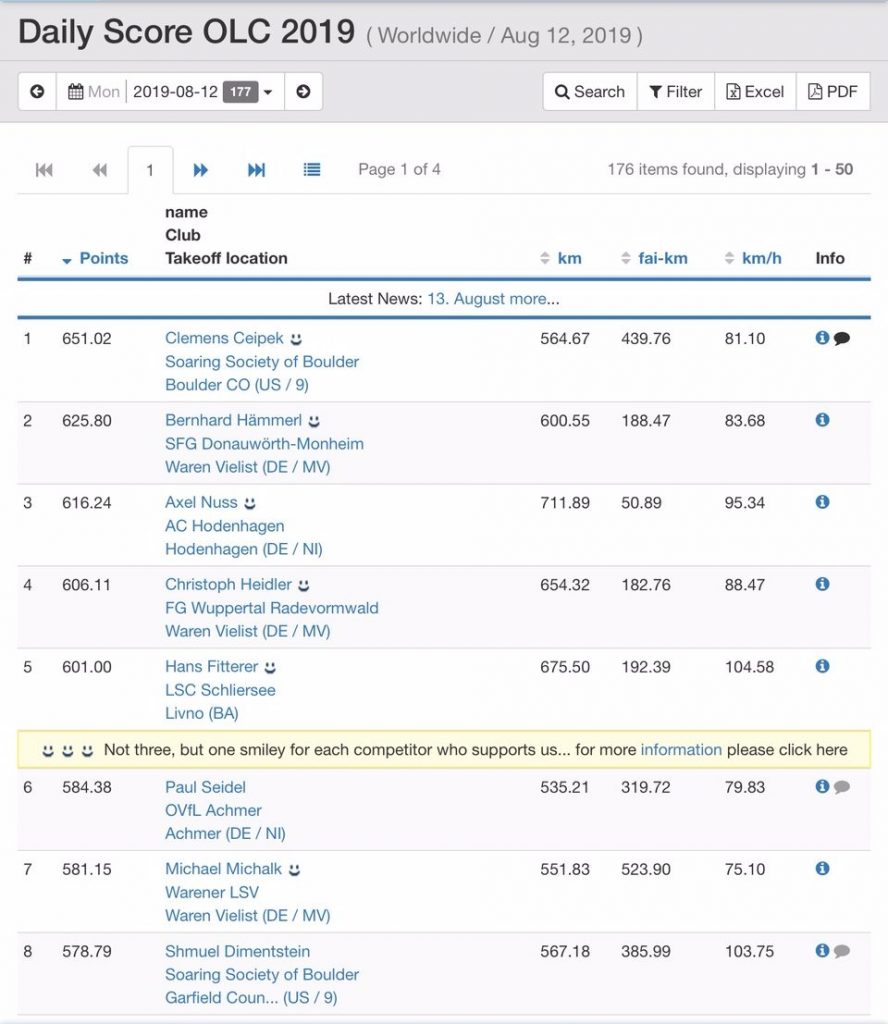

My OLC flight distance based on optimized six legs was 564 km with an embedded FAI triangle of 439 km (also my biggest yet). One day later I also noticed that the flight was the highest scoring flight for the day worldwide with 651 points on OLC plus. The flight track is here.

Lessons Learned

- Don’t Give Up. It took me six attempts to make Diamond Distance. It’s eminently doable without taking any risks but it requires a really good day and a bit of luck. (My bit of luck was the perfectly aligned convergence line at the end of the day that allowed me to cruise to TP 3 and the Finish without turning.)

- Yay to the West. The Continental Divide can be intimidating because it can get in your way on the return to Boulder. But flying in the west certainly isn’t any harder than it is in the east. And the terrain towards Kremmling is much more hospitable with better landing options and good low-traffic airports within easy reach. If you pick the right day – you want high cloud bases, good thermals, modest winds, and a low risk of over-development – then you’re set for a lot of flying fun.

- The Height of the Cloud Bases Matters a Lot. Obviously this isn’t a new lesson but this flight really drove it home. You must always factor this into your flight planning.

- Stay Above the Ridges. This is one of the main principles of early mountain flying that I was taught in Austria. Thermal lift is almost always best above the ridge lines. Ridge lift will work best at ridge top level but you have to be sure about the strength and direction of the wind. This is not a given because often the wind aligns with the direction of the valleys looking for the path of least resistance. Being on top of the ridges also gives you the best view, the smallest chance to get lost, and the widest choice of thermals to pick from. So in short, especially when flying across unfamiliar terrain, it is always best to stay well above the ridges.

- Carefully Examine the Forecast for Good Lines and Select Lines Over Hospitable Terrain. Skysight correctly predicted the energy line to the west across Granby, Kremmling, and beyond. The line extended much further than I could even see. I’m pretty sure I could have kept going west for another 50 to 100 miles. (I just would have run out of day coming back). Lines that run over landable terrain with good airports are the best! The easiest starting point to find good energy lines in Skysight is by looking at projected XC speeds throughout the soaring day. This combines the forecast for thermal and convergence lift. You will then want to validate your choice by looking at cloud bases, thermal strength and a low Buoyancy/Shear ratio (indicated by “stipple” on the thermal strength chart).

- My Flight Planning Strategy Worked (summarized at the beginning of this post). After five failed attempts I had learned from prior mistakes. If you plan your first long flights I recommend you adopt a similar approach to planning your route.

- Fly Around Decaying Clouds. Expect to find sink underneath. A slight detour can be a better option, especially one that takes you across an actively developing cumulus.

- Cloud Shadows Indicate Clouds Streets. When flying close to cloud base it can be impossible to see the direction of the street ahead. But the shadows on the ground are a great marker.

- More Field Walking Is Required. On my next drive out west along I-70 I will want to check out a few fields north of Silverthorne. It was tempting to try soaring the ridge along the Ptarmigan Mountain but without having seen the fields at the bottom of that valley this was clearly a no-no. (I have researched several fields in this area via Google Maps but my degree of confidence in a field improves hugely after seeing it on the ground.)

- How Do I Determine the Height of the Working Band? I could have flown much faster, especially on my leg to the west into the headwind, had I been more choosey about the thermals I picked. But this would have meant being comfortable getting lower before picking a thermal to climb in. Without experience in the area that I was flying in, I had no idea how low I could let myself get before having to worry about climbing back up. I still don’t know. If you have any tips, please let me know!